Jordan Elgrably

The question seems to answer itself, but does it? Are we what we do? And if so, how did a Moroccan who grew up near the Sahara become an Arabic-language professor at the University of Pennsylvania, with more than a dozen books in English to his credit?

In his latest collection of poems, Chasing a Moving Landscape (Lavender Ink, 2022), Mbarek Sryfi waxes at length on his journey, which has not been without pain. In “At Home” he writes:

Through the drapes

I contemplate the snowflakes falling

Dance as they catch the light

Providing me relief

In the moment,

Lost for words,

I marvel at the sight

Lingering on the memory of all I have lost.

The poet, married with a daughter and son (twins), has become an American, but Morocco is in his soul. “How quiet my world is,” he goes on in “At Home.” “One must subdue exile or otherwise by stifled by it.”

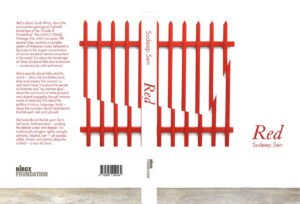

But in his American exile, Sryfi has been anything but stifled. He has translated into English (with Eric Sellin) one of Morocco’s greatest novelists and thinkers, Abdelfatto Kilito, in Arabs and the Art of Storytelling: A Strange Familiarity (Syracuse University Press, 2014). He has brought into English from Darija the prolific Moroccan poet Hassan Najmi, in The Blueness of the Evening (University of Arkansas Press, 2018). And he has introduced to English-language readers the poetry of Aicha Bassry, in With Urgency, A Selection of Poems (Diálogos, 2021). In her eponymous poem “With Urgency,” Bassry could be describing the life of Mbarek Syrifi himself:

No one has desired me

With such urgency as has death.

I have lived many lives in my metaphors.

That is how I extended life

And forged a small eternity for myself.

Throughout the poems in With Urgency, Bassry — a feminist and a prolific poet and novelist — ponders life with sorrow, morbidity and pessimism, because death is her subject, and yet Mbarek Sryfi, her translator and champion, celebrates her work, as if Bassry is an exemplar not of the philosophy that life is about dying and death, but about existence as an in-between state. We exist between life and death all along, and poetry reminds us both of our mortality and our vitality.

In “That Which Suits Death,” Bassry reveals:

In “That Which Suits Death,” Bassry reveals:

A part of me had died.

And what remains has not yet understood

The meaning of life…

Did my father not realize

—When he named me Aicha—

That we do not live,

But spend life yearning,

Seeking a place to die?

At a glance, Bassry’s poem seems bleak, but in between death and life is where she finds sustenance, as does Mbarek Sryfi as he glides between Arabic, French and English. Without a doubt, Sryfi found sustenance in translating Bassry’s “Oath of Love”:

I promise you and swear on it that:

If you were the beat, I would be the heart.

If you were the teardrop,

I would be the eyes.

If you were the pain,

I would be the body.

Even if you were a death

I would be the tomb…

I can truly swear to you a now,

And not promise you a tomorrow.

Again, who is Mbarek Syrfi? In the preface to City Poems (L’Harmattan, 2020), his friend and co-translator, the late Eric Sellin, described him as “a translingual poet,” raised “in a region where diglossia and heteroglossia had already prevailed due to such historical events as colonialism, trade-route contact, diasporic flight, and catastrophic natural or man-made disasters.”

Sellin pointed out that Mbarek Sryfi’s poems are composed “in a direct and unpretentious style” with “an egalitarian outlook and a concise, fully committed limning of characters, landscapes, and various objective correlatives or relics of the human condition.” Yet, often the character Sryfi returns to is himself — the Moroccan, the Saharan, the American, the Pennsylvanian, the husband and father. In “The Stranger Under the Cold Sky” he writes:

A quiet morning

Windless

You could hear the snowflakes falling

On the trees

Snow white

Covering the land

In the cold

He was not the person he used to be

He never knew how to behave at the moment of departure

He never thought about exile

Let alone the concept of exile

He drew his strength from his suffering

To return to Sellin’s preface for a moment, we learn something more about Sryfi, who for years now, “has been exploring and mapping the physical and emotional highways and byways of global migratory and diasporic psycholinguistics in nuanced confessional poems, whose candid observations manage to weave together the memories and impressions of Sryfi’s two main formative cultures into one coherent existential tapestry.”

In several of his poems, Mbarek Sryfi laments the loss of something, perhaps a desertic North African landscape, a community of family and friends who are Darija or Tamazight speakers, or a past that bottles memories that are vastly different from the memories produced during his decades in North America. And, at the same time, per Sellin, Sryfi lives “the excitement of having the opportunity to re-invent oneself.”

We might well wonder how Mbarek Sryfi eased into writing in English. Did he go from classical Arabic to Darija, and then French, then English? What was his linguistic journey, and how does he now feel, as an American-Moroccan and English language writer?

I wrote to Sryfi, and waited patiently for a reply, which came weeks later:

“When I received your question about my relationship with the English language, I was in the process of preparing a testimony about Jack Kerouac, which raised more or less the same questions.

“Growing up in Morocco, I spent most of my time feasting on Arabic, French, and later English books. As a teenager, I was a bookworm looking for books at the school libraries and/or at neighborhood bookstores (small shops where dedicated people would buy used books and rent them to students for pennies), browsing over them, collecting them, and more often than not trading them with friends.

“Such a linguistic journey left a long-lasting impact on my intellectual life. Reading in Arabic and French, and later in English, redefined my awareness of my own place in the world. In addition to Alf Layla wa-Layla (A Thousand and One Nights), Ibn Khaldun’s al-Muqaddimah, Taha Husayn, al-Manfaluti, Jules Verne’s Le tour du monde en 80 jours, Tolstoy’s Guerre et Paix, Dostoevsky’s Crime et châtiment, Emile Zola’s Germinal et L’assomoir, just to name a few, I happened to encounter Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which set my future and the American dream began for me.

“Borges has said in an interview, ‘I think of reading a book as no less an experience than travelling or falling in love.’ As a teenager, my perspective on life changed and I felt that I was a citizen of a greater world. The result was that it inspired confidence in me, and I embarked on an endless journey of reading in English that shifted my early academic interests. After high school, I enrolled in the Department of English at the University of Sidi Mohammed ben Abdellah in Fez, and that further revealed English literature to the young student I was. I never expected that after earning a BA in English Language and Literature that I would teach English and later in 2001 move to the United States, nor did I foresee (aspiring to) becoming an American-Moroccan and English language author.”

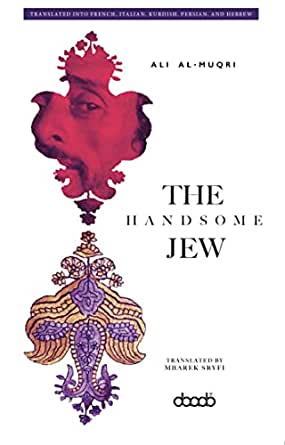

Thus, as a translingual poet and translator, Mbarek Sryfi is a diplomat of language, a builder of linguistic and literary bridges, a friend to Moroccans and Americans*, a go-between when it comes to Arab-Western relations — see his latest translation, The Handsome Jew, by Yemeni novelist Ali Al-Muqri (Dar Arab, 2022) — and a friend to many of his own compatriots, among them, of course, Aicha Bassry, Abdelfatto Kilito and Hassan Najmi, but also the essential Moroccan storyteller, Muhammad Zafzaf and many others he has championed since he journeyed to the United States and became a new citizen.

Exile, as the prime in-between state, has its rewards.

“On the Road” by Mbarek Sryfi

Like a tormented soul, like a leaf in the wind,

I am restless

Like a fraught heart. I am on edge

Like the throbbing of new words — as they

Stroke the page — as they

Breathe the air of so many places — as they

Impart a new life — as they

Become a journey

Into the blue sky, the horizon, the clear nights

Where the stars — like a lonely lighthouse —

Will you to scour the self.

I remind myself of how I longed to take a flight —

Like a warbler —

To flit about in the clouds,

To belie my unquiet spirit

I am restless

Like a sprout seed

In the soughing wind

From which shall grow a penstemon

I will always be solitary,

But free.

* The Kingdom of Morocco was the first country in the world to recognize the new United States, on December 20, 1777.