White Torture: Interviews with Iranian Women Prisoners, by Narges Mohammadi

Forword by Shirin Ebadi, translated by Amir Rezanezhad

One World Publications 2022

ISBN 9780861545506

Kamin Mohammadi

Narges Mohammadi is one of Iran’s foremost human rights activists and vice president of the Defenders of Human Rights Center in Iran. A professional engineer, she lost her job in 2009 following a jail sentence. Since then, Mohammadi (no relation to this writer) has spent most of her days in prison in Iran. Currently, she is incarcerated in the notorious Evin prison, where she has been since November 2021 — the same year that she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Her activism has been recognized globally by human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and PEN, and she is a prominent writer of articles and essays. It is her campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty, women’s rights, and the right to protest that has condemned her to a life of fighting for her freedom.

Since becoming a prisoner herself (even her husband was jailed for years following their marriage and now lives in exile in France with their daughter), Mohammadi has sought to bring to light the cruelty of the solitary confinement form of punishment used by Iranian authorities against prisoners of conscience like her. Extended solitary confinement with extreme sensory deprivation is called “white torture.” It is recognized the world over as psychological torture and a severe violation of human rights, yet is widely deployed by the Iranian security forces against political prisoners. Having suffered this torture herself, Mohammadi campaigns passionately against it; her documentary White Torture won an award at the International Film Festival and Human Rights Forum in 2022.

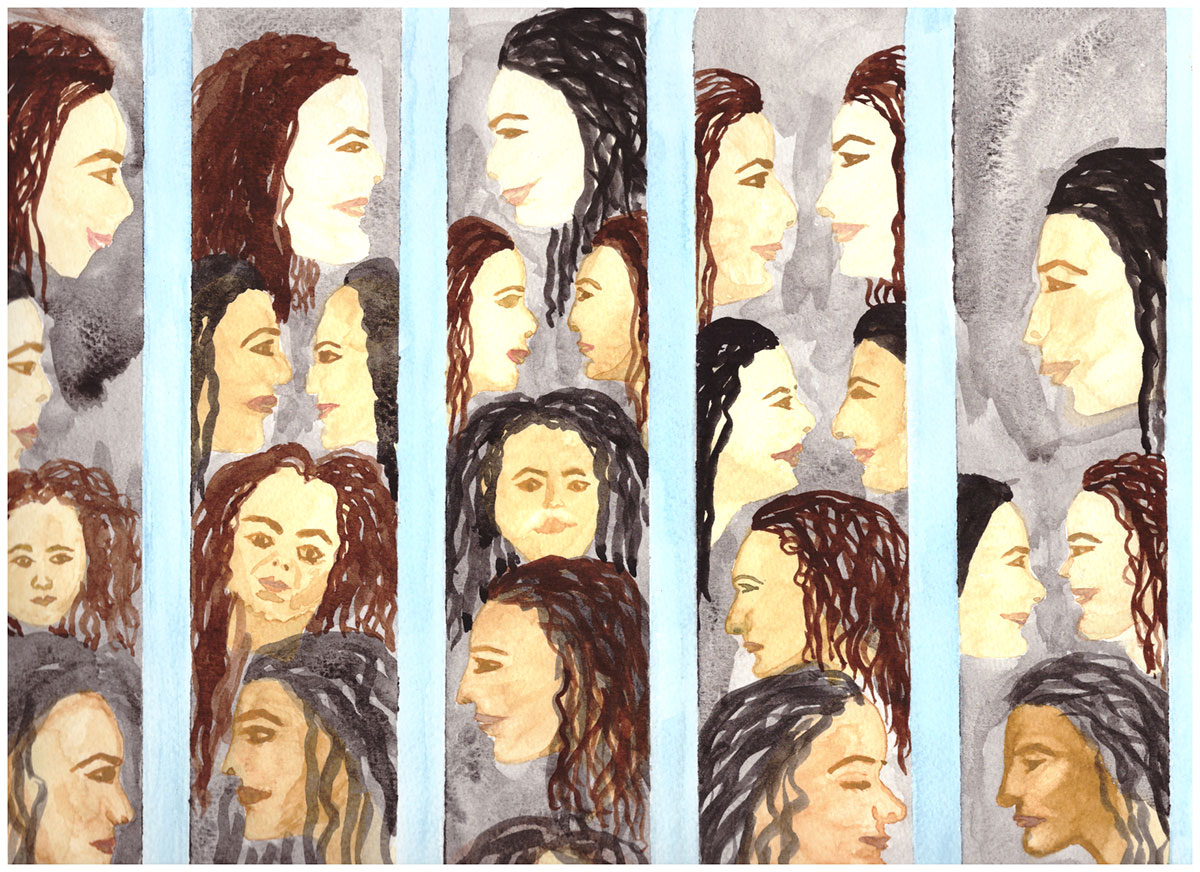

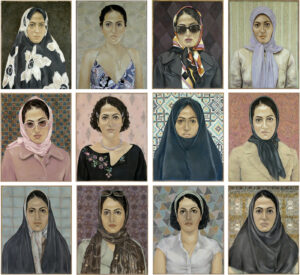

White Torture is her most thorough crie de coeur yet, combining as it does her own heart-rending testimony with interviews of 12 other imprisoned women, none of whom have committed a crime, and all of whom have been held for long periods in solitary confinement — including recently released British-Iranian Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe. These testimonies are uniquely powerful, as all the interviews were carried out while the women were in jail, and make the book White Torture an important document in the fight for human rights. Mohammadi’s introduction immediately stuns the reader, both for the shock of the treatment she has suffered and the matter-of-fact courage and dedication with which she confronts the injustices she faces.

The book opens with these lines: “I am writing this preface in the final hours of my home leave. Very soon I will be forced to return to my prison… This time I was found guilty because of the book you are holding in your hands – White Torture.”

That was in March of last year. Mohammadi had been briefly released from jail because she had had a heart attack and required cardiac surgery. Now she is a prisoner again and sentenced to 11 years in prison, and part of her sentence will be spent in solitary confinement. “I declare once more that this is a cruel and inhumane punishment,” she writes. “I will not rest until it is abolished.”

This book throws light on the extraordinary inhumanity with which the Iranian regime treats its opponents — like all paranoid dictatorships, it sees opponents everywhere — and lays bare the extent of its brutality against its own people. Now more than ever, as protests continue across Iran and are brutally repressed, understanding the crimes and systematic cruelty of the regime has become a matter of urgency.

Since women-led protests broke out in Iran in September of last year, sparked by the death of Kurdish-Iranian woman Mahsa Jina Amini at the hands of the Morality Police, the full force of the Iranian regime’s security apparatus has been used against the protestors. Hundreds are dead while an estimated 20,000 have been arrested (as figures cannot be verified, they are probably much higher), four executed, and dozens sentenced to death. Many of the protestors, artists, activists, and those arrested have been systematically tortured and raped, according to social media testimonies and a report from CNN; several of them have committed suicide on being released. Doctors and lawyers helping protestors have also been targeted by the authorities, and many injured protestors do not dare go to hospitals for fear of being arrested.

Jailed Iranian American Siamak Namazi, who has been held in Evin for more than seven years, mostly in solitary confinement, recently completed a hunger strike in protest at his ongoing detention and the failure of the US to secure his release; in a statement to the press, he praised the courage of the many women and other activists also being held in Evin and their ongoing fight for justice. Mohammadi is one of those activists.

The women Mohammadi interviews in this book include a children’s rights activist, a Baha’i, an activist against judicial corruption, a Sufi who converted to Christianity, a woman who was caught up in a street protest, and, of course, Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who was charged with spying but never really understood why she had been taken; they are a representation of the randomness of reasons for which the regime can incarcerate people and throw them into solitary confinement with no respect for their human rights.

The testimonies are tough reading at first, but then the common themes start to emerge and begin to fascinate, most strikingly the velocity with which mental and then physical health starts to break down once the senses are deprived in a small silent room and all humanity is drained from life. The prisoners variously describe their happiness in finding an ant in the tiny cell and stopping a fly from escaping so they could talk to another living creature. The delight of the woman who finds a butterfly in her tiny 2×3 meter cell one day is palpable, as is the joy of another who hears a bird sing. The regime’s contemptuous disregard for human life is evident in how it neglects those women who become ill and often end up with life-changing health conditions. Hengameh Shahidi, for example, who was given almost 13 years for complaining about judicial corruption, is still under medical treatment since being released last year and has been unable to resume her normal life. All the women recount their desperation at being separated from their children and how they are haunted by anxieties for them. Zaghari-Ratcliffe describes her prison encounters with her daughter:

Gisoo had accepted that her mother lived in a room and she said this repeatedly. She cried when she had to leave, and I was very upset. When I returned to my cell, I could smell Gisoo’s scent on my body and it was painful. When Gisoo asked me to go to Grandma’s house, I didn’t know what to say. I was exasperated. Every time she cried goodbye, I would break down. The interrogators were present in the meeting room. When sayong goodbye, I wanted to go ahead and tie her shoes for her, but they wouldn’t let me and I had to leave her.

Yet it is not just horror and a deep sense of disgust at this injustice that the testimonies provoke. With each interview, the courage and dignity of the women, their strength and integrity shine through even as they recount how psychological torture was applied to try to break their spirit. The details are surprising, as is the realization that solitary confinement is not just a physical space but also enacted through the way prisoners are treated and denied their rights and even humanity by the guards, who at best ignore them and treat them with disdain. Yet resilience underpins the interviews, and the self-assurance of the women is inspiring. Marzieh Amiri, a journalist and women’s right activist, declares:

In prison, the interrogator is not merely an interrogator, but a representative of the patriarchal order that silences your voice if you refuse to do what he wants. In this system, you can have a legitimate presence, be seen or respected, but only if you are tame, obedient and committed to maintaining and enforcing the existing order.

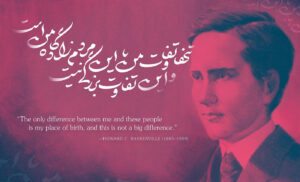

Mahvash Shahriari, who was awarded the PEN Pinter Prize of International Writer of Courage prize for a volume of her prison poetry in 2017, and is currently in custody on charges of spying again, sums up the deep impact of white torture on the prisoner: “To be isolated from the passage of time, to be isolated from society, to be removed from the natural cycle of life, and to be thrown into a corner out of reach, is the definition of solitary confinement.”

This book makes for compelling reading on many levels, not least when it comes to showing the extraordinary spirit of Iran’s women and their devotion to justice and freedom. It also makes an urgent case for the abolition of the insidious and cruel form of torture that lends its name to the book’s title, and gives us a horrifying glimpse into the mentality and apparatus of Iran’s security forces. It is no wonder that Shirin Ebadi, Iranian human rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 2003, writes in the introduction: “Narges still roars like a lioness. This is why the regime wants to crush her. White Torture is another roar of this lioness.”

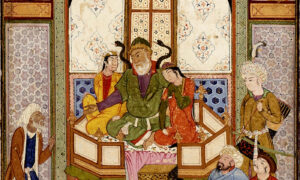

What an insightful piece into this dark corner of the human experience. Even as an Iranian-American I was not aware of the extent of the cruelty of white torture, unjustly robbing innocent women of their mental and physical agency. While difficult to read, I am once again blown away by the courage of the Iranian women who maintain their dignity and pride despite incredible odds. How these women have and continued to suffer is is heartbreaking, but their bravery gives me hope that there is light at the end of this dark tunnel of injustice. The accompanying art is quite moving as well.