Jasmin Attia's novel vividly portrays Egypt and Cairo by beautifully conjuring music and sound through descriptive prose.

The Oud Player of Cairo, a novel by Jasmin Attia

Schaffner Press 2023

ISBN 9781639640201

Jasmin Attia’s The Oud Player of Cairo starts with the third-person narrator informing us that Kamal Abd El Malak, an oud player of rural origin, “loved Egypt the way a man loves a woman.” The beloved’s “beating heart” is Cairo, to which Kamal has moved to work as an artist. Egypt as a whole and Cairo in particular are portrayed in descriptive prose that often beautifully conjures music and sound:

He loved [Egypt] from her blue Mediterranean north to her green lush south, where he’d once farmed sugar cane and pomegranates. He loved the way her rippling Nile stretched through her, how her plains flooded. He loved her deserts bare and foreboding, torrid by day and cool under velvet night. But most of all he loved her Cairo, its beating heart of music and dance and poetry and scholars and films and cars and buses and vendors. He loved the ma’asil tobacco that the coffeehouse waiters packed into the hagara and the percolating sound of the shisha. He loved the scent of coffee boiling in a kanaka every morning in his kitchen; the warm pita that when torn open let out a cloud of bready steam; and he loved his first daily bite of hot fava beans seasoned with lemon, oil, red pepper flakes, and cumin.

In an early scene, we are led along meandering streets filled with all manner of music and sound until we arrive at the place where Selma, Kamal’s wife, is giving birth. Laila, Kamal’s second daughter, is entering the world, thereby shattering her musician father’s illusion that he is about to have a son. Upheavals — inner and outer, emotional and embodied — will characterize the life of Laila, who emerges as the protagonist of Attia’s debut novel. The Oud Player of Cairo offers a series of intricately painted snapshots of a country that is being battered by competing political tidal waves. It is told through the thoughts of a young woman who inhabits a tumultuous and even traitorous world. Laila’s father dies when she is still young, but his lasting imprint on her mind makes her measure every twist and turn in her life against what she imagines her father would have said or done.

Laila’s story begins in the Cairo of the early 1930s and runs through the early revolutionary years that divided the century, and its history, in unmistakable ways. A father’s struggle to accept the reality of female offspring ushers in the real story, that of a little girl growing up with a rare kind of confidence in a social pyramid that places her firmly at its base. Not even a woman yet in a patriarchal society, Laila discovers the social order around her bit by bit, as she discovers life. The young Christian girl adores her father, a man of humble stock and a musician to boot. Is the story meant to be about him or her? That is the point.

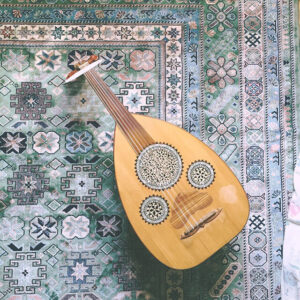

I don’t know if the idea of upheavals came to mind because, as I read the novel, I was taking regular walks along the wintry Mediterranean corniche of Alexandria, sometimes passing beaches that were visited by Laila and her aristocratic husband in a bygone era. Or if it was because I was following the thoughts and feelings of a protagonist who goes from being a poor girl whose father teaches her to fight like a boy if she has to defend herself to a grown woman who is dressed by Europe’s most exclusive fashion brands of the time. Laila’s trajectory is unpredictable, taking one sudden turn after another, much like those of her country and its capital. She experiences a conservative Coptic Orthodox upbringing in which the body’s beauties and desires are vehemently denied, only to become an opulent married woman whose body is forced to transform into a locus of pleasure in ways she has to discover on her own. Time and again, Laila’s body and emotions are at odds. Only music makes her whole: singing, which she loves, but also her father’s oud. As she grapples with constant oscillation between competing and at times even contradictory emotions, singing gives Laila solace, and her father’s oud offers similarly reassuring sentiments.

Attia kneads music into a narrative of life and memory through the journey of a protagonist who is a singer in her own right but who also moves within the orbit of an instrument: her father’s oud, which Laila spends years trying to find after his death. The symbolism of Kamal’s oud and in particular its sound, which haunts his daughter, is strong. The instrument is at once dispensable and focal in the main protagonist’s narrative. Laila has never played this oud, yet she obsesses about it; it was lost, yet it becomes something akin to the linchpin of the story. This interplay between what is and what isn’t, the real and the imagined, exemplifies the novel’s layering of contradictions, as does the exchange between thoughts and feelings.

In Upheavals of Thought, Martha Nussbaum tells us that emotions are best construed as thoughts. Emotions are also related to conceptions of virtue, and hence to religion and religious belief. Attia portrays this potently in relation to the story’s immediate setting of a Coptic Cairene neighborhood and Laila’s Catholic schooling, as well as in relation to the wider Islamic environment of working-class Cairo — all of whose leanings were conservative, even in the relatively open pre-revolution era. Considered from a wider angle, emotions are related to ethics and moral judgment. In The Oud Player of Cairo, this is sensitively explored through the protagonist’s interiority, from the questioning thoughts of her child’s inquisitive mind (which get little Laila in trouble she soon learns to avoid) to her adult mind’s decisions, which enable her authentic self to emerge from crucibles of song and pain.

In recent years, philosophers and neuroscientists have started moving towards agreement on the ways in which people intuitively understand, live, and practice emotions. Attia’s stylistic trope of multilayering, namely her writing sound onto visceral descriptions of other sensory experiences, is a literary attempt at bridging the gap between cognition and emotion. The early scene in which Selma gives birth to Laila weaves together gory bodily detail with sensations of intense pain, screams, and ethereal musical sensibilities.

But there is more to this story of emotion, cognition, the body, and literary experience, specifically in the realm of ethical judgment. Though the author seems to want to avoid issuing moralistic verdicts through Laila, she does not always succeed. The protagonist’s successful negotiation of her world’s right and wrong is mostly imposed on her by figures and arbiters of authority throughout her life (mother, nuns, social norms, class, wealth, colonial powers, intrusive neighborly eyes, gossip, and Nasserite officers, among others). Yet despite otherwise carefully balancing her characters’ opinions with factual descriptions, the result is sometimes a binary take on the world around the protagonist, with the extent of authorial distance remaining unclear.

Attia introduces interesting twists in her storytelling. But sometimes descriptions of highly charged moments pass without dramatic treatment. Life-altering and potentially traumatic experiences, including instances of extreme bodily aggression — of the kind that would scar the victim physically and psychologically for life — are sometimes rendered in single sentences. By comparison with the graded palette of sensations that Laila experiences, which Attia painstakingly layers with overtones and undertones, instances of extreme aggression are conveyed passingly. Whether this is a deliberate decision on the part of the author or a blind spot is difficult to determine.

Yet here, perhaps, is where the reader ought to avoid the temptation of judging the author’s intentions. Instead, we might note the agility with which Attia demonstrates the complexity of Laila’s inner and outer worlds. The former is where her thoughts and emotions roil. And the latter is where a girl belonging to multiple disadvantaged minorities negotiates a survivor’s existence in a place and time where the odds are firmly stacked against her, and against her marginalized father.