“Please Patterns” & “Complexifying Restitution”: Myriam El Haïk and Jihan El-Tahiri at the Berlin Biennale

Viola Shafik

The 12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Arts is about to come to an end, yet it might be worth musing on its main themes, to examine how this “edition brings together artists, theorists, and practitioners from different fields to let them enter into a dialogue with the city of Berlin and its public,” and consider whether speaking to some of them may provide further insight on why the German capital has become such an art hub in recent years. Can we indeed follow the Biennale’s statement for this purpose? It attests that Berlin “is continuously under change thus remains fragmented, diverse, and contradictory.”

Coincidentally — or not (!) — we found that two of the present Arab female artists, Jihan El-Tahiri and Myriam El Haïk, even though keeping a strong foot in Paris, have both moved to Berlin five years ago for reasons that will be explored below in detail. With regards to the current exhibition, their respective contributions, the video “Complexifying Restitution“ (2022) and the installation/performance “Please Patterns” (2021-22), fall into the multitude of terms that the Biennale’s “Messy Glossary” offers for its core concept; that is, the “de-colonial.” It touches upon topics as varied (and as cryptic) as hydro mysticism, the exotic, extractivism (the process of extracting natural resources from the earth to sell on the world market), but also as iconic as cultural heritage, institution, imperialism and so forth.

Sifting through the Biennale’s artist inventory, the quantative “Arab” presence seems quite striking, certainly unlike what is usually the case at the Berlinale Film Festival, for instance. Apart from the already mentioned El-Tahri and El Haïk, we find the late Amal Kenawy (Egypt), as well as Ammar Bouras (Algeria), Asim Abdulaziz (Yemen), Bassel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme (Palestine/USA), Driss Ouadahi (Algeria/Germany), Lawrence Abu Hamdan (Arab Emirates), Lamia Joreige (Lebanon), Layth Kareem (Iraq/France), Raed Mutar (Iraq), Simone Fattal (Lebanon/USA), and Taysir Batniji (Palestine/France). These are fourteen among a total of more than eighty artists, without counting those involved in the different group presentations, as well as the Biennale’s artistic team members.

The latter includes Lebanese curator Rasha Salti, based partly in Berlin, who has been also responsible for an attached film series, and of course even more importantly, Kader Attia, the Biennale’s chief curator (interviewed elsewhere in TMR’s BERLIN issue). Born to Algerian parents in France, he too lives between two cities, not Paris though but Algiers and Berlin. Artist and activist, Attia has repeatedly focused on decolonization, not only of peoples but also of knowledge, attitudes and practices. His latest take on the topic is called “Caring, Repairing and Healing,” which he will feature in his upcoming exhibition (Sept. 9, ‘22- Jan. 15, ‘23) at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin.

According to Attia, the notion of “repair” is “first of objects and physical injuries, and then of individual and societal traumas. Little wonder this topic also features prominently at the Biennale, with one of its numerous encounters and conferences called “From Restitution to Repair“:

Participants investigate the psychological dimensions of the loss of cultural heritage in Africa and the paradox presented in mimical museography. The contributions explore the possibility of an ontology of restitution as a cosmogonic, political, and philosophical reinvention. —Berlin Biennale

This again is exactly what the Beirut-born Egyptian Jihan El-Tahri is engaging with. Previously a reporter and journalist, she has become an acclaimed filmmaker, mentor and visual artist. The Biennale website quotes her: “Working primarily with installation art, she often engages with the interstices between official history and memory in an attempt to reinterpret the moments of our history of which no traces have been left behind and to propose a new reading and alternative voice from a Global South perspective.“

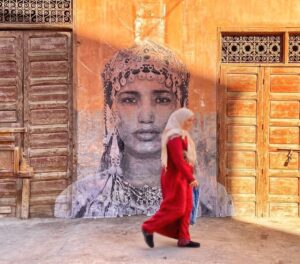

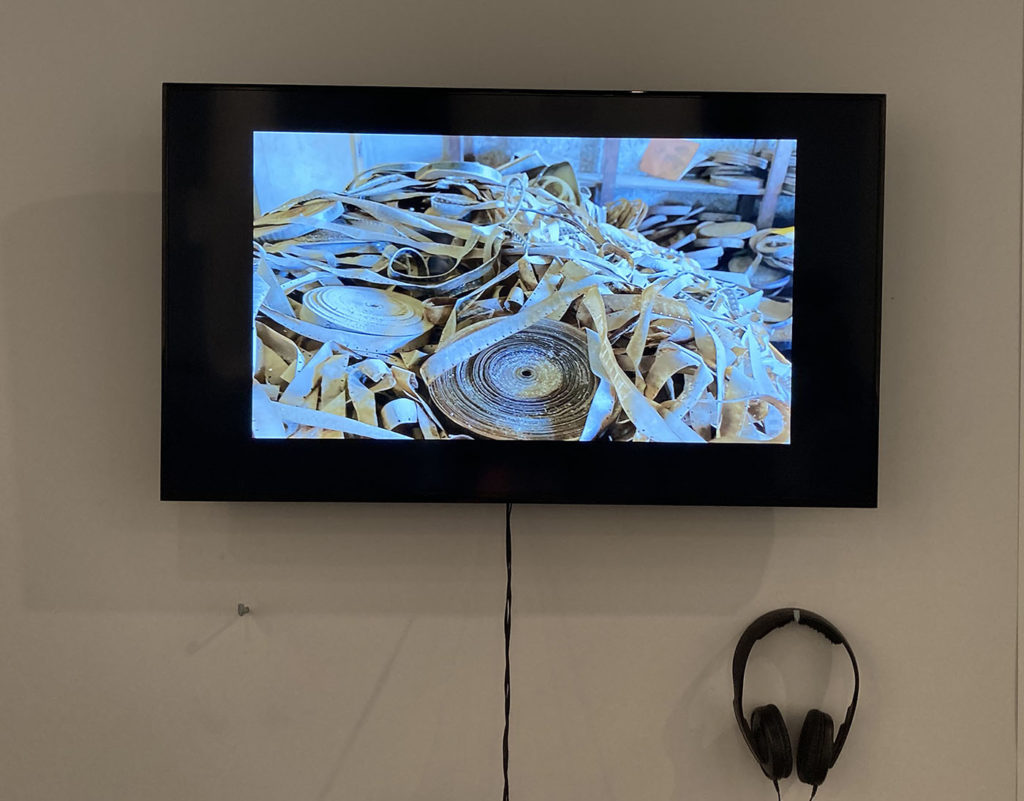

In her 15-minute video “Complexifying Restitution,” El-Tahri uses archival and her own documented material (some of which mirrors her preceding documentaries) on researchers, artists, and filmmakers to interpret, rethink, and reappropriate the archive. “Accordingly, every piece of found imagery is critically probed, scrutinized, and contextualized,” starting from so-called ethnographic colonial footage to the ambivalent images of Nubians cheering Egyptian national leader Nasser for his decision to flood their homeland for the sake of modernization; or even more painful, the testimonies of Guinean cinéastes remembering those who were sent to study film in Moscow, only to be persecuted and even eliminated when they came home.

El-Tahri, born into a diplomat’s family, toured the globe as a child. In her conversations, she switches instantly from French to English to Arabic. For many years she made Paris, among other cities, her home, but she feels similarly rooted in sub-Saharan Africa and has kept her previous domiciles in Dakar and South Africa. Constantly on the road, changing her many professional hats all along, she radiates the centered agility of a swirling dervish. Hence, one of the many things she manages, apart from traveling from one film festival to the other to help train young African and Arab filmmakers, is to run the nonprofit Dox Box, headquartered in Berlin.

The association was originally established in Damascus in 2008 and run by ProAction, the first independent documentary production house in Syria, owned by Orwa Nyrabia and his spouse, Diana El-Jeiroudi. They organized a festival that became a hub for young Syrian filmmakers. After the Syrian uprising, the couple moved to Berlin and widened the institution’s scope, catering mentorship, residency programs and an annual convention for Arab filmmakers along with Syrians. Eventually, five years ago, El-Tahri was appointed artistic director and has broadened the focus once more to encompass programs for sub-Sahara and female documentarists. This appointment, in fact was the reason why she moved to Berlin. And as she confesses, even though she has decided to quit her job at Dox Box in order to focus more on her artistic work, she will keep one more domicile to remain connected to Berlin.

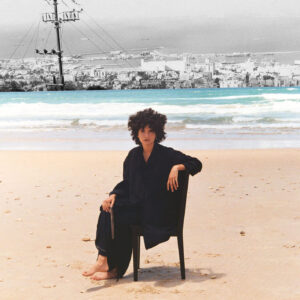

Myriam El Haïk too, like her fellow artist, commutes between different cities and countries, in her case Rabat, where she grew up; Paris where she studied fine arts and music composition; and Berlin, where she has her work space and young family. Despite the fact that she is similarly a lively, petite woman, the difference in artistic expression could not be larger between El Haik and El-Tahri. For her work has little to nothing to do with audiovisual politics of representation or film archives, but all with visual and sonic memory, with music, rhythm and patterns as they inhabit time and space, or rather, create interstices between them. Her “Please Patterns” is a piano piece she composed, its rhythmic and melodic fragments were inspired by her drawings and her collection of Moroccan “Berber” or Amazigh rugs that are also part of the show.

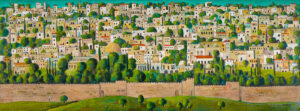

Her “repetitive minimalist aesthetic,” as she calls it, runs through as a series of displayed drawings, and a polyptych wall drawing that she continues doing once every week together with piano performances to become a regular ritual throughout the 12th Berlin Biennale. Here she wants to offer “the experience of an unfolding time.” Watching her meticulously crossing out the little squares of a grid reminiscent of our school math booklets during her performance, a meditative silence emanates from her contained movements, and the overall formal experience definitely reminds you of the wealth of abstract art forms practiced in her homeland before the advent of European style figurative arts, starting from calligraphy up to ornamental arts. And she does everything to underline their cultural implications: “One and the same thread appears to be running from the ancestral tradition of weaving to the act of drawing and eventually to contemporary music: a thread of ritualized time that links writing to speech, the visual to sound, the score to the music. Perhaps a time like that so aptly and genuinely conceived by the Arabic language — without an imperfect or future tense — a time shared between the completed act and the unfinished.”

Quite tellingly, it was El Haïk’s love for music and patterns which became the tipping point for moving to Berlin. With a music piece in mind, she walked through the streets to find the light reflecting on the windows creating various patterns that inspired her. She found herself additionally attracted by presence and history of the Bauhaus, that genuine architectural and design movement, in the city. Moreover, bringing out her inner child, she experienced a playfulness much more developed than elsewhere.

Last but not least, what she underlines as one of the most positive assets for her is the curiosity and the openness of Berlin’s public and its curators. While in Paris she found herself confronted with “identitarian” policies. These relegated her abstract minimalism to her homeland and confined it to art spaces like the Institute du Monde Arabe. In Berlin, in contrast, she found herself received and perceived as what she was — a member of a global art scene without ethnic or cultural classifications. This argument, it seems, not only confirms the Biennale’s statement about Berlin’s changeability and fragmentary character in a positive sense but could explain as well why it has become so attractive for Arab and non-Arab artists to work and reside here.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)