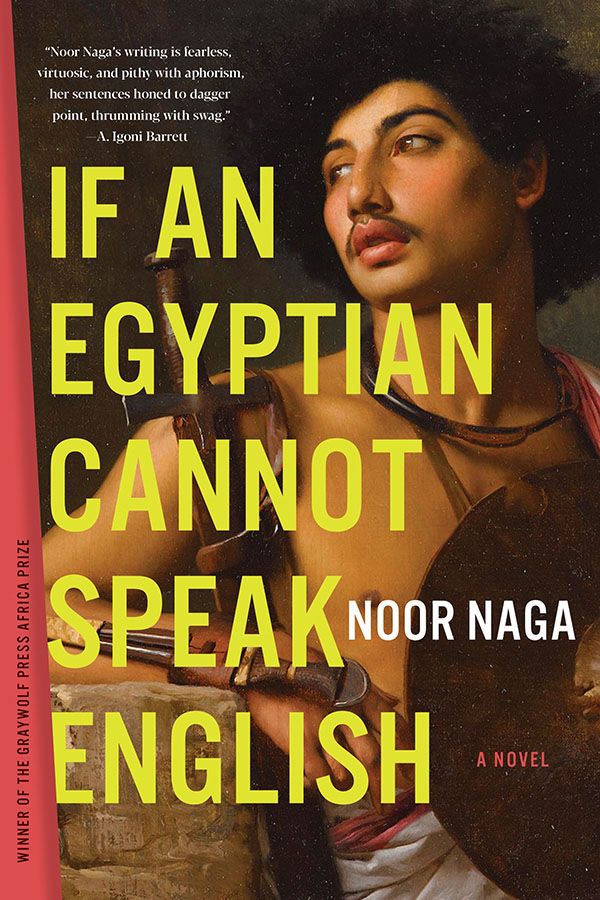

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, a novel by Noor Naga

Graywolf Press 2022

ISBM 9781644450819

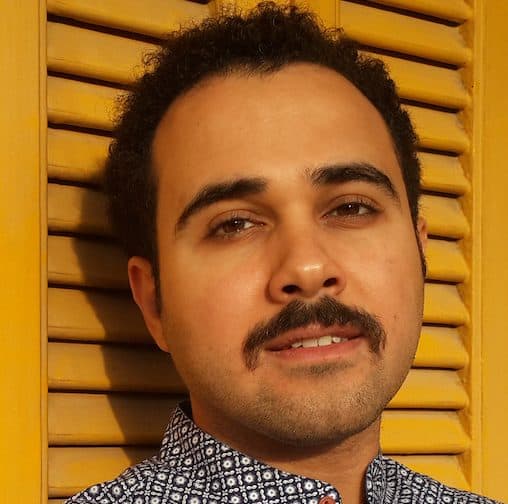

Ahmed Naji

Translated from the Arabic by Rana Asfour

We find ourselves in Cairo in a post-2016 world, when a bald American girl arrives in what she feels is her homeland and the origin of her roots. Reading between the lines, we gather that she’s left America, fleeing from a sadness that she does not disclose. We know, because Noor Naga tells us from the first chapters that the American girl keeps shaving her head, but what she does not tell us is the reason behind her decision to remain bald. We also know that she is the daughter of Egyptian immigrant parents, that she graduated from Columbia University in New York, and that her father is a practicing physician in a clinic in the heart of Manhattan. Shocked at her decision to visit Egypt, her mother nevertheless makes the necessary calls, after which the daughter arrives, stays in a luxurious apartment in one of Cairo’s most affluent neighborhoods, and obtains a tidy job as an English teacher for adults, at the British Council.

Noor Naga begins her novel If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English with the promise of intense drama. An escape story, a trip home, secrets to unravel, but what truly gets one involved in the reading is her immensely fluid prose, as each sentence forces one to stop long enough to savor it slowly — prose that is highly complex and supremely intelligent.

When I arrived at Ramses Station in Cairo, the air was people. Nowhere you looked wasn’t people. They clogged every street and then piled on top of each other in buildings twenty stories high. Many were not even Egyptian. You could turn into an alley and find fifty Sudanese men, bluer than black, with cheeks like shoulder blades and ankles like knives, or else women as tall as I am, women so pale you could see rivered blood at their wrists and neck. I heard twenty Arabics in my first week and wherever I went people asked me — sometimes in English because of the hair — Where you from?

Naga’s novel is divided into three main parts. In the first movement of the operetta, there are short pieces, each one limited to two pages in length. They all begin with “What if” and have a transcendent feel to them: “If you don’t have anything nice to say, should your mother be punished?” The narration alternates between two voices, the American girl and a boy from Shobrakheit, who appears as a partner in the novel. Naga describes his upbringing in a village on the margins of the Egyptian countryside, raised by a possessive grandmother who envelopes him in a private world, in which she feeds him with her hands. The two share a bed and bathe together. When his grandmother dies in 2011, he heads to Cairo with his camera, a gift from his grandmother, only to arrive in a city that is in the midst of a revolution. He soon finds himself part of a new group being shaped by the city’s tumultuous uprising, streets, city squares and gas bombs.

Enraptured by the new social order, he captures it all on his camera, and it’s not long before the TV stations and news agencies are racing to publish the photographs he takes from the heart of Tahrir, the Square, that document the clashes taking place. Two years later, the revolution is defeated, and the now world-class photographer from Shobrakheit loses his sense of purpose and questions the meaning of his existence, hanging up his camera and refusing to take any more photos that would document a “fake reality.” With dwindling resources, he moves into a hovel in one of Cairo’s boroughs. His subsequent addiction leads him on a path of self-destruction.

By this point, readers can easily predict how the rest of the story will unfold. The American girl will meet the boy from Shobrakheit, they’ll fall in love, until it all dramatically falls apart. It’s a tale that’s been repeated over and over again in fiction, particularly in the years following Egypt’s 2011 revolution. A popular tale because of its intimacy, especially for a reader like me who lived his life in downtown Cairo and witnessed the beginning and end of dozens of such similar stories. Moreover, for the past decade or so, this is a theme that has been recurrent in Egyptian literature written in Arabic. What Naga does however, is turn this straightforward, simplistic theme into horrific scenes and landscapes in which social class and political identity clash, culminating in a tragic crime.

Egyptian Literature

The history of Egyptian literature, written in English, can be divided into two phases. The first is Egyptian writers born and raised in Egypt for whom English formed an essential part of their education due to their social class, such as Wajuih Ghali, Samia Serageldin, Ahdaf Soueif and others. A sense of alienation presents itself in various forms in the writings of that period, mainly a sense of not belonging within the class the writer occupies. The only exception, perhaps, is Wajuih Ghali, who rebelled against his own class, certainly in the novel Beer in the Snooker Club.

The second phase includes writing from the children of Egyptian immigrants, which began in the ‘70s and continues to this day. According to official Egyptian government figures, the number of Egyptians residing abroad is close to ten million. Estimates from the Egyptian embassy in the United States put the figure of those who live in the US at one million, though this is contradicted by the US Census Bureau, which estimates Egyptian emigrants at a quarter of a million. Regardless of these different figures, this nation of millions living in the diaspora has become part of the modern Egyptian identity, reshaping the meaning of Egypt, and presenting its image through its artistic and literary works, especially as many within this group possess material and scientific capabilities that allow them the power of autonomous representation, or as Naga asks in her novel, “If an Egyptian cannot speak English, who is telling his story?”

Noteworthy is the fact that Egyptians residing abroad who speak different languages — and like the protagonist of the novel study in prestigious universities — transfer, according to the Egyptian government’s latest figures, more than 30 billion dollars annually to the country, representing 8% of the government’s total budget. And so the question that one asks oneself here is if the American girl, with her English, is really able to tell the tale of the boy from Shobrakheit.

Language, English in this case, is an impediment that imposes a rift within the life of the American girl moving to Egypt, and those around her. Her poor command of Arabic exposes her and makes everyone ask her where she’s from. Add to that the writer’s decision not to name her protagonist, to refer to her only as the “American girl,” seems to enforce that idea, despite her Egyptian heritage and time spent in Egypt, language continues to be a barrier to communication, even after she falls in love with the boy from Shobrakheit and he moves in to live with her in her luxury apartment.

The boy from Shobrakheit, who was raised in the care of a smothering grandmother, sits next to the American girl while she eats and expects her, like his grandmother, to feed him. The American feminist soon finds herself in a relationship that has turned her into a dispossessed woman — one who goes to work in the morning, while her male partner sits at home waiting for her to come back to cook and clean, while he does nothing except watch videos on YouTube.

The American girl soon loses herself within a world dominated by Arabic and a system of social codes that she is unable to decipher or navigate. Subtly, changes within her behavior take shape in a before and after Egypt form. Prior to her arrival in Egypt, the American girl had been a political activist, who had once revolted against a man and led a whole subway car against him in New York when she witnessed him harassing a veiled woman. The scene had been filmed and even gone viral. However, in Egypt, we see her remain silent, when her friend, the owner of a famous restaurant, refuses to seat two veiled girls in his establishment, because their hijab would put off the “clean Egyptians,” the rich bourgeoisie, decked in Western brands.

In the second part of the novel as the two voices continue to alternate, Noor Naga introduces detailed footnotes that readers assume are likely guidelines for familiarizing the non-Egyptian reader with Egypt, such as its foods that include the different varieties of mangoes, as well as foul, our traditional dish made of fava beans. However, as an Egyptian, these footnotes left me ill at ease, as they appeared to contain errors and factual details that did not add up. I was particularly drawn to one referencing a Nubian writer by the name of Sayed Dhaif, whom I had never heard of and could not find in any of my searches. When I sent the author an enquiry, she admitted that she had, in fact, invented the character. He was not real and neither were a number of other “facts” in her footnotes.

And so it is that the author sets up several traps in the novel for the reader who looks upon literature as an accurate representation of its subject. She ingenuously casts these traps to mimic the American girl’s interpretation regarding the realities of life around her in Egypt, in which she fails to distinguish between the facts and lies that the boy from Shobrakheit makes up. The ensuing confusion and the difficulty of differentiating between the multiple narratives around what is real and what isn’t reaches its climax when it comes to the details of the pair’s relationship. The scene that the boy from Shobrakheit paints is one of unbridled love, while the American girl portrays one of violence.

Trapped within a relationship in which she is unable to distinguish between love and abuse, things escalate slowly until at one point, the boy from Shobrakheit hurls a coffee table at her, inflicting severe wounds and bruises. It is only when the boy from Shobrakheit finally disappears that she is able to return to the remnants of her former life. She ends up meeting an American man living in Cairo, and further entanglements ensue when the boy from Shobrakheit dies, a mystery readers will have to work out for themselves.

Naga plays around with light and shadows, and like a magician manipulates the reality we see in front of us, making us doubt the veracity of whatever her narrators tell us right up to the moment when all is revealed in the last chapter.

Throughout the novel, Noor Naga toys, like a magician, with light and shadow, obscuring certain details while revealing others, casting doubt on everything, right up to the final chapter in which readers encounter the American girl, back in America, discussing, with colleagues in a creative writing class, the final chapter of her novel.It’s a final chapter that readers of this novel aren’t privy to but rather garner its content from the commentary of the American girl’s classmates as they share their critical take on it. The American narrator’s colleagues discuss her novel filtered through the lens of a contemporary American values system as one colleague objects to her empathy with the boy from Shobrakheit, arguing that her writing serves to perpetuate sympathy for the oppressor, and legitimizes violence against women.

Another reader asks the writer for more details related to Egypt, mining her for exciting features that play to an imagined sensibility of a distant place. All the while, the American girl is silent, happy to merely take in the comments, as if the author, having explained her two protagonists in previous chapters, surprises English readers with a mirror that reflects their own questions. In the end, it is one colleague only who focuses his comments on the technical components of the novel and advises her to delete the last chapter, which is exactly what she does. Hence, its unavailability within this novel despite everyone talking about it in this novel’s final chapter.

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English is a novel much like Egyptian mangoes, whose taste lingers on the tongue long after the last bite.