Despite its repressive regimes, Saudi Arabia has produced a number of world-class novelists — several of whom have seen their best work banned. Rana Asfour reviews three in English translation.

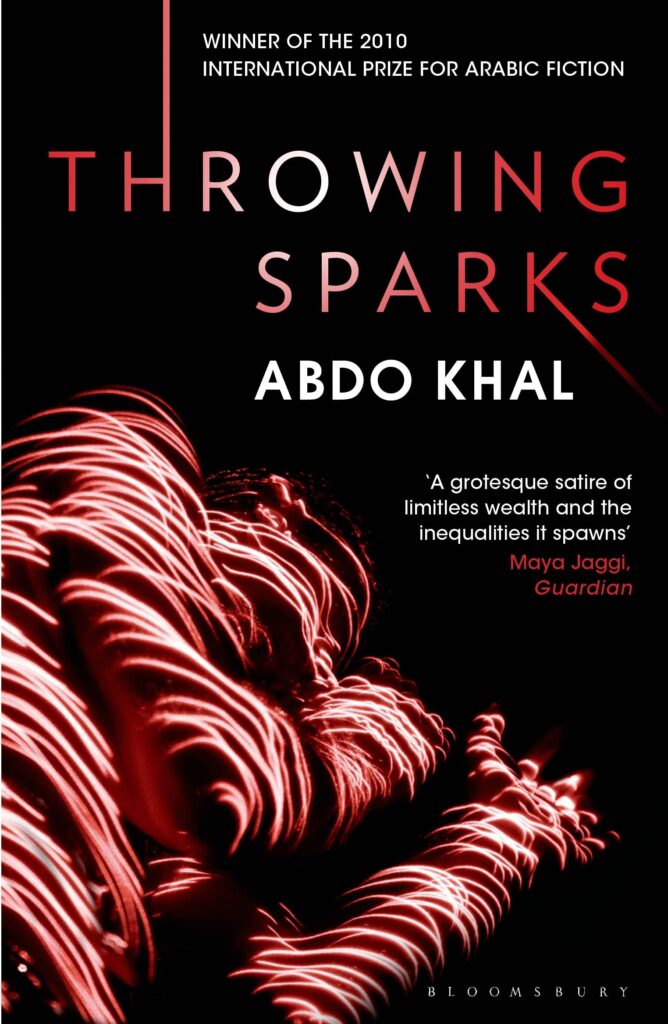

Throwing Sparks, a novel by Abdo Khal, translated by Maia Tabet & Michael K. Scott

Bloomsbury, Qatar Foundation Publishing (2014)

Reporters Without Borders has described the Saudi government as “relentless in its censorship of the Saudi media and the Internet,” and in 2021, it ranks the country 170th out of 180 countries for freedom of the press.

That said, however, what was obvious at the Riyadh International Book Fair, held in October of this year, is that books long since considered taboo or controversial in the Kingdom were for the first time, being displayed on shelves. Visitors, speaking to media outlets, expressed astonishment at finding books on Sufism and atheism as well as long-banned books by classic authors such as Dostoyevsky and Orwell (1984) corroborating the government’s Vision 2030 that “books lay at the heart of its reforms campaign.” This was in vast contrast to the 2014 fair, in which organizers had confiscated more than 10,000 copies of 420 books.

In an interview with the UAE’s The National newspaper in October, Mohammed Hasan Alwan, Chief Executive at Literature, Publishing, and Translation Commission at the Saudi Ministry of Culture spoke of the “cultural transformation” led by the Kingdom’s youth who with the government’s blessing are hoping to “elevate the kingdom’s status as a literary and cultural hub both in the region and internationally.”

Despite the emerging glimmer of hope that many bans would be eased on authors’ works, unfortunately there still remains a long list of banned books and authors, for reasons that at times seem baffling. For the three authors whose novels we review below, the government continues to uphold its decision to prohibit their books in the Kingdom, despite their availability on the Internet. The silver lining? Banning a publication more often than not cements its fame.

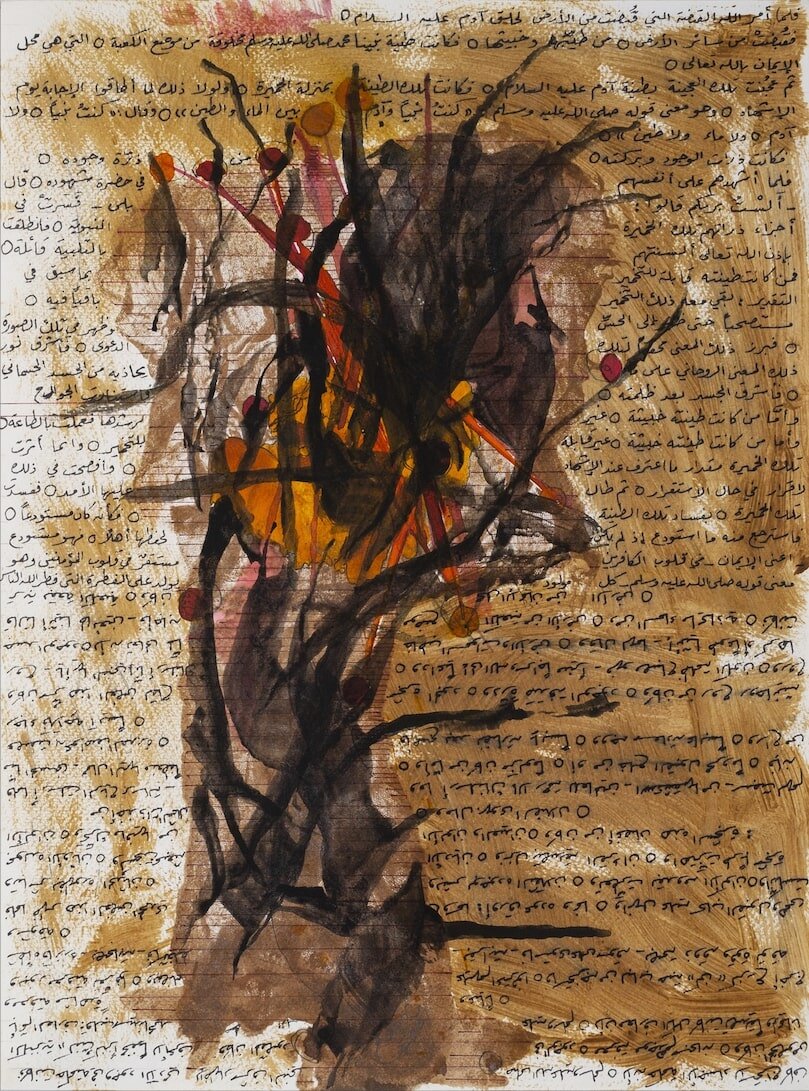

Abdo Khal’s Throwing Sparks (Tarmi bi Sharar) won the 2010 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) and Khal has been called a “pillar of Arabic literature.” This satirical novel is incendiary from the word go, beginning with Khal’s choice of title: a partial Qur’anic verse from Surah Al-Mursalat, Aya 32, that describes the fires of Hell as large as castles. The novel swirls around sodomy, corruption, shame and injustice, all taking place within a castle situated on the waterfront of a country considered to be the cradle of Islam’s birthplace. Of course such a fiction was never going to go unnoticed, hence it came as no surprise when it was banned in Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries, as was the case with all Abdo Khal’s previous works, the exception being his 2005 novel Fusooq (Immorality).

Despite this, the author and journalist still lives and works in Jeddah. He is the author of a dozen books, including A Dialogue at the Gates of the Earth; There’s Nothing to be Happy About; and Cities Eating the Grass. Some of his novels have been translated into English, French and German. In addition to his writing, Khal is a member of the board of directors of the Jeddah Literary Club, and the former editor-in-chief of the Ukaz newspaper, for which he writes a daily column.

The novel’s jaw-dropping first chapter ensnares the reader, and the first few lines of the Arabic version are as a noose that wraps itself firmly around the reader’s neck, tightening and restricting the passageway of air with every turn of the page. A book not for the faint-hearted, critics have described the graphic torture scenes as “revolting.” Khal relentlessly shows no mercy as his characters nonchalantly mete out injustice, and only a few pages into the novel, the reader quickly learns to expect that no mercy will in fact be forthcoming.

The novel follows 51-year-old Tariq whom we meet reminiscing about his life and lamenting his 31 years lost in the service of the “Master” — the cruel, immoral owner of the magnificent castle despite the newspaper and magazine photographs that suggested “an amiable and gentle-hearted man who was virtuous and righteous to a fault.” Tariq is tasked with the job of sodomizing the Master’s rivals, and “not dismounting the victims until after he had pounded them to a pulp and all that remained was a heap of moaning and gasping bones,” all while the latter and his cohort watched on, in amusement, from outside the torture chamber.

In between his “tasks” Tariq has fallen in love with the Master’s mistress Maram, whom he likens to “touching a live wire” as untold misery awaited anyone caught glancing her way when she was in the Master’s company or when she stepped out onto the dance floor. With each new “task” and every passing year, Tariq grows increasingly richer and more powerful, eventually exacting his own vengeance on those he blames for his moral detriment and sullied existence.

When I met Abdo Khal at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai in 2014, the thing that stayed with me after a very brief conversation preceding his talk was his insistence that whenever he writes and however painful what he writes about is, he always comes to the work from a place of love. He added that despite being possessed and obsessed with the novel’s storyline, he nonetheless had to stop several times during the writing of this novel in particular, feeling ill at the words and ideas spewing out onto the page, yet feeling helpless and unable to stop them from flowing nonetheless. He was eventually hospitalized and it was the encouragement of his wife who spurred him to complete his work as he’d faltered many a time, unable to go on.

And go on he did. The novel contemplates sensitive, often volatile issues with respect to Islam, sexuality, morality, masculinity and honor. In a scene where Tariq approaches his loathsome aunt and wonders if he was there “to give the lie to all her dire warnings or to confirm them,” one cannot but pause, reflect and wonder whether such a book, with such a dark horrific message, is actually conducive of dispelling the myth that already surrounds a country shrouded in gossip and mystique, or whether fuel has been added to an already raging fire.

From a different standpoint altogether, it serves well to remember that, based on the author’s biography printed on the inner flap of the English-language hardback copy, Abdo Khal started out as a preacher, before turning to full-time writing. One wonders whether that makes this painful, dark satirical novel that throws light on the excesses of the rich and wealthy — whom Tariq calls “deviants and perverts…motivated by boredom: tired of what is socially acceptable, they seek whatever is novel or uncommon to break the monotony of routine pleasures” — a calculated decision on the author’s part, not too far afield from his preaching days. In that light, one could argue that the castle of Hell that Abdo Khal conjures up in his novel is no more than an elaborate form of cautionary sermon to warn people of the consequences of sin and vice and their detrimental effects on individuals and societies; a Hell on Earth and damnation in the afterlife in which as readers venture towards the end of the novel, God is ultimately The Gracious and Most Merciful. The perfect ending to a perfect sermon if ever there was one.

Cities of Salt, a novel by Abdelrahman Munif

Vintage (1989)

Still banned in Saudi Arabia after all these years, Cities of Salt was written by Abdelrahman Munif in exile in Paris, and later published in Beirut in 1984. It is a blistering look at Arab and American hypocrisy following the discovery of oil in a poor oasis community. Set in what could easily be the eastern Arabian Peninsula where Saudi oil was first discovered, the novel stretches from the 1930s to the 1950s and offers not only a glimpse into the “butchery” of the landscape in which “the trees cried for help, wailed, panicked, called out in helpless pain and then fell entreatingly to the ground, as if trying to snuggle into the earth to grow and spring forth alive again,” but it also sheds light on the decimation of the core values of Saudi’s Bedouin societies within the Peninsula as well as the raging rise of political Islam in the region at the time.

Described by some as the greatest “petrofiction” novel written after WWII, Cities of Salt is the first in a quintet that together consist of 2,500 pages, making it the longest novel in modern Arabic literature — one committed to the author’s vision to see an Arab world freed from what he once described as the “trilogy of oil, political Islam and dictatorship.” It has been described by Edward Said as “the only serious work of fiction that tries to show the effect of oil, Americans and the local oligarchy on a Gulf country.”

This incisive historical novel begins with the poor inhabitants of an oasis in which the bonds of family and religion hold everyone in perfect harmony. When oil is discovered by Americans invited to search for it by the country’s ruling elite, they shatter the tranquility that once pervaded the area. The impact of modernization rushes to the forefront and readers get a keen sense and understanding of the resentment the locals feel toward the callous and unjust non-Muslims whom they blame for the increase in materialism and loss of spiritual and communal values, and a backward, paternalistic local government that ignores the pressing social problems.

The novel roams along with nostalgia for the “simple” past in which the “wadi’s people were known for their strange mixture of gentleness and obsession.” Described as “peaceable and happy,” with the tribes’ ancient myths and magical superstitions a lamentation of today’s contemporary truths, Cities of Salt excels at documenting clashes both absurd (the sets of jumping jacks performed by the non-Muslims at dawn are seen as demonic practices by the oasis workers awakening for prayer) and the much more serious and volatile, such as the workers’ strike in 1953 and other events loosely based on real political events.

When British author and leftwing activist Tariq Ali asked Munif what “cities of salt” meant, he explained, “Cities of salt means cities that offer no sustainable existence. When the waters come in, the first waves will dissolve the salt and reduce these great glass cities to dust.”

Abdelrahman Munif was born in Jordan in 1933 into a trading family of Saudi Arabian origin, though his mother was Iraqi. He was stripped of his Saudi citizenship for political reasons in 1963. He studied law at Baghdad and Cairo universities and took a PhD in oil economics at the University of Belgrade. During his oil industry career he served as director of crude oil marketing. In Baghdad he edited a monthly periodical, al-Naft wa al-Tanmiyya (Oil and Development). He later became a full-time writer and spent the rest of his life in Syria. “Oil is our one and only chance to build a future,” Munif once told Peter Theroux, the translator who would bring Cities of Salt into English “and the regimes are ruining it.”

Adama, a novel by Turki al-Hamad translated by Robin Bray

Saqi Books (2003)

According to Adama’s publishers, Saqi Books, al-Hamad’s explosive novel became an unlikely bestseller in the Middle East, selling more than 20,000 copies despite being officially banned in several countries, including the author’s native Saudi Arabia when it was published in 1998. Set between the late sixties and early seventies, Adama is a compelling coming-of-age story that explores issues of sexuality, underground political movements, scientific truth, rationalism, and religious freedom. Adama is the first in Turki’s trilogy to be translated into English; it is expected that a translation of the second instalment, Shumaisi (also by Saqi Books) and the final instalment al-Karadib will follow.

In his tranquil middle-class neighborhood in Saudi’s oil province, Dammam, eighteen-year-old Hisham doesn’t quite fit in. He believes in two imperative truths: education and making his family proud.

As he boards a train to take him to the university, flashbacks of his life show him as a budding philosopher who spends his days reading banned books (which he has to lie about) and developing his political ideals, particularly books on the banned Ba’athist party for which he becomes a spokesperson. His Saudi Arabia is a nation embroiled in internal conflict, torn between ancient tradition and newfound prosperity. Hisham finds himself caught up in the struggle for change, devoting more and more of his time to a shadowy group of dissenters even as he questions both their motives and methods, and continually berates himself for “being such a disobedient son.”

The result is an intense showdown between Hisham’s love for his family, his firmly-held philosophies, and his yearning for social justice. He awakens to passions both private and political, coming to grips with the paradoxes of a conservative land where illicit pleasures co-exist with the apparatus of a merciless state. Adama ends with the protagonist getting off the train to start his life at university.

Turki al-Hamad is quoted on the cover of one of his novels: “Where I live there are three taboos: religion, politics and sex. It is forbidden to speak about these. I wrote this trilogy to get things moving.”

Turki al-Hamad is a highly successful author in the Arab world. His novels are controversial throughout the Middle East; he is the target of four fatwas (religious edicts) claiming his life. He is the author of Shumaisi, also published by Saqi Books in London. He continues to live in Riyadh and teaches at the American University in Beirut. Al-Hamad was arrested December 24, 2012 after a series of tweets on religion and other topics. He was freed in 2013.