In a Libyan village called “Hell” — where temperatures soar to unimaginable heights — an unofficial war might have started over a parking space in the shade of a mulberry tree.

In a Libyan village called “Hell” — where temperatures soar to unimaginable heights — an unofficial war might have started over a parking space in the shade of a mulberry tree.

Mohammed Alnaas

Translated from the Arabic by Rana Asfour

The conflict in Jahannam was never random; it makes no sense to believe otherwise.

Rumors suggest that it all began when Jamal Tshenkwi, the village’s notorious drunkard, secured a position as the head of the People’s Trustees of Jahannam, making him the first alcohol dealer ever to do so. Colonel Boudabbara, Tshenkwi’s rival, questioned his ability to fulfill his responsibilities to the constituents. This led to three months of intense fighting between the Tshenkwi rivals and Boudabbara’s Party, who adamantly refused to relinquish power to the Bukha merchant, ultimately dragging the entire village into conflict.

It’s also been said that the discord between the two men had been brewing for a long time. Many believed it all started the day when Colonel Boudabbara bought a bottle of Bukha from Tshenkwi. When it failed to intoxicate him and he complained, Tshenkwi cut off his supply and refused to serve him ever again. From that moment on, the Colonel was left to suffer his memories of the harrowing Chad War and the ghouls that pursued him through the night, all while completely sober.

Other narrators allege that the conflict began further south of the Sahara, near the Chad border. Allegedly, Tshenkwi, a soldier in the Colonel’s brigade, and his platoon were abandoned by Boudabbara who managed to escape in a French supply plane when surrounded by the devilish leader Idriss Deby’s convoy, leaving the alcohol merchant to suffer his darkest days imprisoned in the cowsheds of N’Djamena. It is said that this event fueled Tshenkwi’s hatred for the Colonel. After this, he bided his time, waiting for revenge. Some suggest that the animosity between the two men was related to honor, possibly involving Jamal’s daughter and the Colonel’s son. There have been many other speculations that are unsuitable to mention here. But between you and me, regardless of the reasons behind the conflict, what matters is that it occurred. Discord, like any human pursuit, requires no explanation or interpretation.

Before you dive into trying to interpret the meaning of this story and its symbols, and whether Tshenkwi and Boudabbara stand in for larger warring forces in Libya or elsewhere, past or present, let me put your mind at ease. This is a true story that took place in the 1990s in a small village called Jahannam, right under the noses of those in power. I, the narrator who has captured your attention, am another storyteller who has altered the story for the sole purpose of amusement and preserving it for future generations who may not be as concerned with the moral of a story as they are with understanding how we once lived in a non-subjugated, albeit marginal country. Our local soft drinks, Saada, Kawthar, Marada, and Tabr, were commonly found in every household. We would refill these bottles at individual retailers or cooperatives. Once broken, we would repurpose the glass shards to reinforce our walls, making them twice the height of an adult to protect our homes from invaders and thieves. During the conflict between the households of Tshenkwi and the Colonel, we repurposed these bottles into Molotov cocktails and used them as makeshift rockets to burn the enemy’s territory.

I know your type, dear reader, so please allow me to further disappoint you. Despite Tshenkwi’s intriguing backstory, depicted through the tattoos splayed across his body that map out tales of past lovers, friends, and experiences both within and outside the country, he will hold a marginal role in this narrative along with Colonel Boudabbara, who arrived in Jahannam the same year a group of his old cronies attempted to pass a pomegranate between the legs of the Leader. Only in deference to the Colonel’s past achievements did the Leader spare him from death and instead stripped him of his titles, leaving him at the mercy of the whittling days. This story is about the village, not because I believe that people are entitled to a record of their battles with their leaders, but because I find it more entertaining when a story is told in this way.

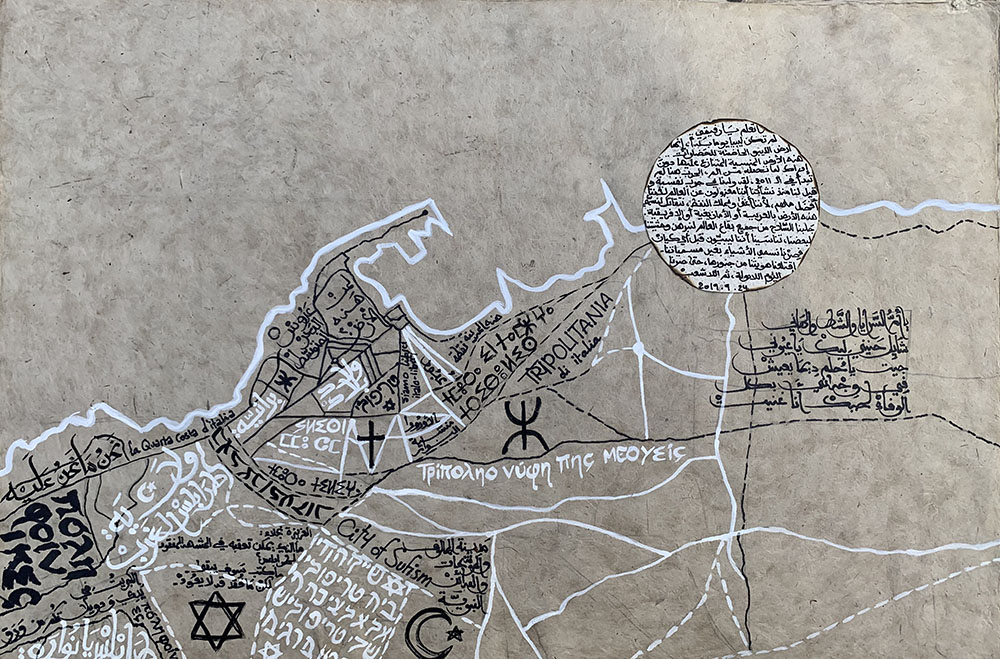

And now, without further ado, allow me to introduce Hajj Imhemmed Bou Mesmar, a descendant of Bou Mesmar El-Sharif. According to stories passed down through generations, his great-grandfather came to this country escaping the Spaniards in Saguia el-Hamra. It’s said that when he settled in Tripoli of the West with his grandchildren, the key to his house in Morocco was left hanging from the lock.

Hajj Imhemmed was awoken when a photograph of him, wrapped in his ihram clothes and taken in a studio in the center of Tripoli, came crashing down after violent tremors ripped through his ancestral home. In the photo, he is posing against a backdrop of one of the walls of the Holy Kaaba, corroborating his deserved title of Hajj. After seeking refuge in prayer from the troubles brought on by mankind and the Jinn, he unleashed a barrage of curses in the language of the Rumi*, with whom he had once long resided, living among their cattle in the barns of Palermo. The Hajj grabbed his crutch, wrapped himself up in his summer cape, and placed his taqia on his head before venturing outside to watch the fire consume the Bronsi palm tree in the center of the courtyard. Quickly, he took the fire hose, started the motor, and attempted to save whatever could be salvaged. He pondered why fate deemed it that his house be situated equidistant between Jamal’s house and Boudabbara’s, but he quickly pushed aside such thoughts, seeking refuge from Satan’s evil and the frailty of the soul. A true believer never questioned his destiny.

After putting out the fire, the Hajj sat down in his chair and looked around at the remains of the palm tree and the area where the Molotov cocktail had landed. He was trying to figure out which of his two neighbors had thrown it, completely forgetting that it was not the Molotov that had woken him up, but the rumblings of his walls, stirred to life by a stronger explosion. After realizing the futility of trying to determine the source of the projectile, he decided to search the debris for any leftover glass shards. He hoped to track down the perpetrator by identifying the brand of the bottle, as he knew every villager’s preferred beverage.

He stood in front of the tree, offered up a prayer for its survival, and then crouched beneath it to search with his cane for any glass remains. Disregarding the shooting pains in his back, Hajj Imhemmed considered how the time had come to choose a side in the conflict after a month of remaining neutral and his unsuccessful attempts at bringing about reconciliation. May God’s curse be upon the bastards, he said after he looked up and realized that the fire had reached the heart of the palm tree, officially announcing it dead and ending any chance it would be used ever again to make al-laqbi juice.

Hajj Imhemmed, Sidi orders that it’s about time the cursed Jamal was expelled from Jahannam.

He recalled yesterday’s conversation with the Colonel when he had walked in just as the Hajj, who was feeling thirsty, was longing for a cup of tea. He hadn’t thought much about the Colonel’s garbled words, especially since it was becoming difficult to understand him given the cancer eating away at his larynx, likely worsened by his excessive drinking and smoking. He also hadn’t paid attention to the words of his son, who now acted as his father’s interpreter.

Only a few days earlier, Jamal Tshenkwi had sought help from his old comrades from Chad, who lived outside the village. This was because Colonel Boudabbara’s attacks had intensified, restricting the flow of customers visiting at the gates of Jamal’s home. The colonel’s army mainly comprised of his children, as well as both declared and secret supporters within the village, outnumbered Jamal and his allies. As the Hajj’s thoughts swirled around the desired cup of tea, it was all he could think about as the Colonel and his son continued their incessant chatter without pause. He vividly imagined the dark tea adorned with the foamy white residue floating on its surface. He could almost taste the intense tang of the tealeaves he had been craving all day. He tried to push aside these thoughts and instead pictured a floating dialogue box, filled with the Colonel’s words, mostly in a language he didn’t understand. Still, he listened to the Colonel’s stories about his time in Italy and Czechoslovakia, excelling at the College of Military Technology before the collapse of the Soviet Union, where he had learned to dismantle grenades, plant mines, and manufacture bombs and missiles.

Before the conflict, the Hajj’s most recent neighbor would reminisce about his former days when he had been someone to reckon with. The Hajj tolerated the Colonel’s boasts about his past heroic exploits and subtly hinted that he, too, used to throw stones at the Italians, stealing from them whatever they could get away with. He remembered hiding with his brother in the village caves for days at a time. It struck him that the Colonel hadn’t mentioned anything about his time among the Communists since the war began.

Oh, finally. The tea. Rejoiced Hajj Imhemmed as he spotted the Colonel’s youngest son carrying the tray of teacups. When he noticed the boy’s hands shaking, he prayed to God that the cups would be delivered safely from the boy’s unsteady grasp. Easy now. Come, hand one to your venerable uncle, the Hajj instructed the boy as he pretended to follow the interlocutor’s speech, barely able to conceal his happiness at the tea’s arrival. At first, he was tempted to drink it all at once, but he resisted the urge. Who knew when he would have another chance to savor another cup that week? He had relied on the Secretary of the Association’s assurances that the tea had arrived from Sri Lanka. A month had passed since then, and there was still no sign of the tea. It seemed that the issue lay with the packaging and distribution factory. They were unwilling to release the shipment because the packaging failed to feature a picture of a Sri Lankan woman. The Hajj recalled telling the secretary that he wasn’t interested in seeing an Asian girl in a red dress and a yellow headscarf picking his tea. As far as he was concerned, he was content to receive his ration in the palms of his hands, just like in the old days.

The Hajj savored his tea, taking his time to convince himself that he was ready to support the Colonel. He was willing to forgo any appeals for reconciliation as long as he could have a cup of tea every day until the government resolved the tea shortage and the supply truck arrived at the Association. Only then would he refresh his proposals for a resolution. After all, Jamal had never once offered him tea during his past visits when he had advocated for calm and conciliation and incessantly appealed to him to seek refuge from the evils of Satan through prayer to God and his Prophet.

Hajj Imhemmed, deliver this message to Jamal: he has one week to vacate the village. Time is running out, and there will be zero tolerance. These were the last words the Hajj heard from the Colonel’s translator. Struggling to articulate the word “zero” to no avail, the Colonel tapped his watch repeatedly to make his point. The Hajj knew it was time for him to take his leave, but he was only halfway through enjoying his cup of tea and wasn’t about to go anywhere until every drop of that liquid was completely consumed.

That had been the previous day. After he’d been woken in the morning, having missed the Duha prayer, he felt no desire to reflect on the war. Instead, he ventured outside to assess the destruction in the street. Standing in front of his house, located in a narrow alley between the Colonel’s house and Tshenkwi’s, he tried to figure out which house had been hit by recent shelling. The wall of Tshenkwi’s house had more burn marks, but so did the wall of the Colonel’s house. What surprised him the most was the gaping hole exposing the operating room on the roof of the Colonel’s house. The sandbags protecting the room appeared to be empty. This marked a new development. Tshenkwi and his allies, renowned for their bravery, had never approached the Colonel’s operations room so closely before. Their previous attacks had always been weak and ineffective, but it seemed they had now made significant progress and were no longer on the defensive.

This means that the scoundrel Jamal Tshenkwi is responsible for burning down my palm tree, he reasoned with himself. He sets fire to my palm tree and refuses to offer me tea, claiming he has none and suffers like everyone else. How can he be like us when the Association’s secretary is his companion during his nights of revelry?

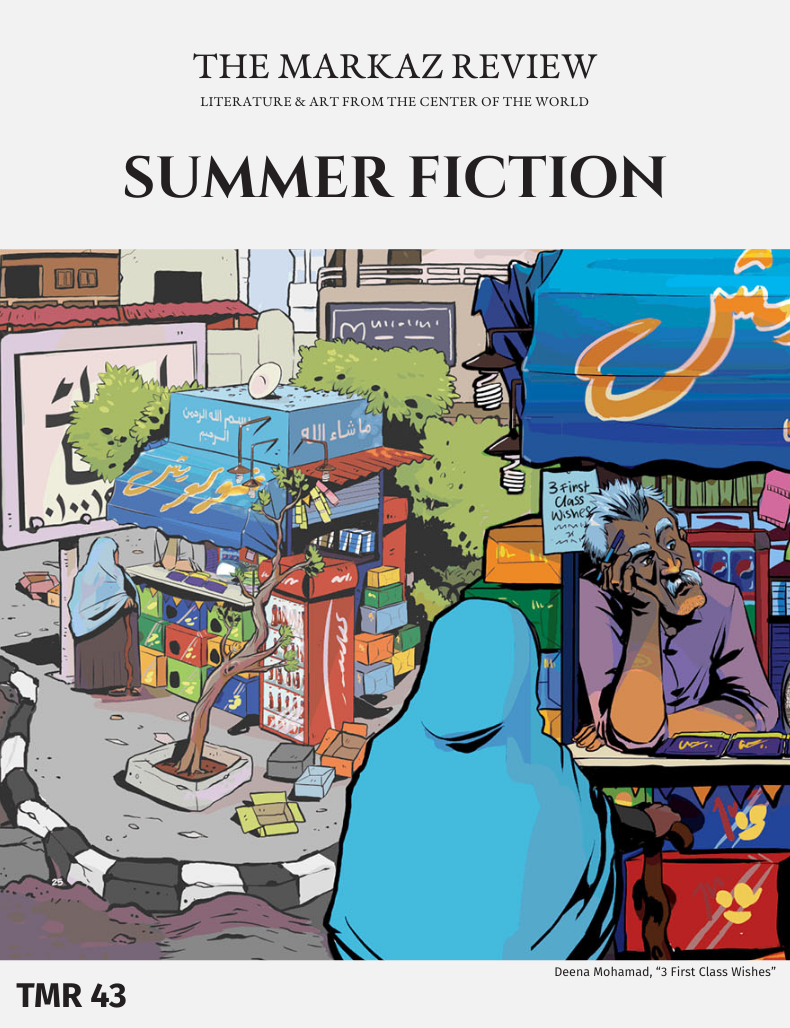

In that moment, he noticed the mulberry tree in the middle of the village. The one he credited to be the main reason behind the conflict between the two feuding families. The tree provided shade from Jahannam’s scorching sun. Tshenkwi always parked his green Volvo, a model from the same year as the 1977 Year of the People’s Power, under the tree. However, once the Colonel moved in next door, he insisted on parking his white Corolla in its place. This model shared the same year marking the end of Chad. Perhaps, reasoned the Hajj, this conflict simply boiled down to a senseless war over cars.

They burned down my palm tree and spared the mulberry. He marked the ensuing stillness, the deserted dirt road emptied of pedestrians, and the general absence of people from the area lined up with rows of the Indian Barbary fig. He roamed the village in search of updates about the conflict and the slim chance of securing another cup of tea.

*Rumi means “Italians” in an old Libyan dialect.