How can someone of hybrid background and loyalties operate in multiple spheres including writing, journalism and politics, where narratives are very often set by people from mono-cultural backgrounds who belong more neatly in one camp or another?

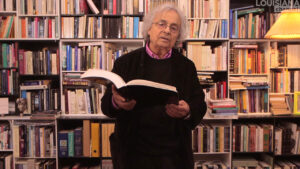

Lives Between the Lines: A Journey in Search of the Lost Levant, by Michael Vatikiotis

Weidenfeld & Nicholson 2021

ISBN 9781474613224

In a world where identities are painted like lines on a football pitch, most of us are expected to pick a team if we want to belong. This seems even more true if one happens to be a journalist, historian or diplomat, who wants their books and ideas to be widely heard in the public sphere. But when you’re the grandson of multiple cultures, ethnicities and nations, you cannot believe and tell only one story, nor be a blindly loyal citizen to only one nation while remaining true to yourself.

So how did Michael Vatikiotis, a man of a dizzyingly hybrid background, navigate the famously tricky worlds of journalism, historical writing (both fiction and nonfiction), and serve as a behind-the-scenes and back channel peace negotiator in some of the world’s most intractable conflicts? I was very curious to hear his story, given that I was a hyphenated writer myself, who had struggled to find solid footing in the world of British broadcast journalism.

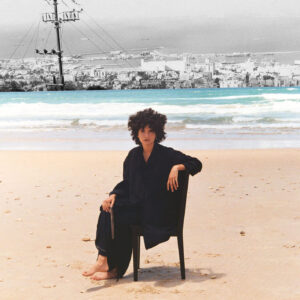

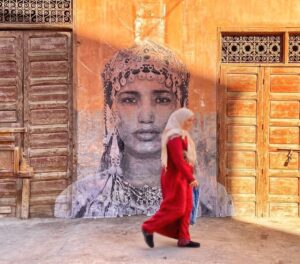

I came to England from Syria with my family at the age of 15, after having only had an Arabic language education, with French on the side and no English. Being Syrian with a Greek Orthodox Christian father and a Dutch Armenian mother who was born and raised in Indonesia and Singapore, I found it difficult to explain my background to others in the largely mono-cultural country that was Britain in the 1980s. Yet in Syria, the heart of the Levant, where I had grown up, such multicultural identities seemed par for the course in a region that had been a cultural and religious melting pot for millennia.

After reading Michael Vatikiotis’ two major books on the Levant and South East Asia, I first got in touch with him for the first time a few years ago, when he was passing through Athens with his Mauritian wife Janick. I felt that I had met a long-lost relative, a cross between European, British, Southeast Asian and the Levantine worlds. Vatikiotis was a writer who had somehow found a way to investigate his own roots and the multitude of worlds he inhabits. He was someone from whom I had much to learn.

Vatikiotis was born in the United States in the late 1950s, in a small campus town in Indiana, where his Levantine father was teaching. He was raised and educated in the UK, living in the North London suburban fringe. From his early years Michael was confronted with the question, “Who are you and where do you come from?” If he had wanted to think of himself as American or British, it was impossible because of the regular questioning implying that he was not and that he must come from elsewhere. His Greek surname, his English accent, his American birth, and later on his taste for Batik shirts, as well as his fluency in Indonesian and Thai, were a cause of confusion, at a time during the last quarter of the 20th century when diversity and multiculturalism were still in their infancy, particularly in the UK, and especially migration from the Middle East, as the majority of British migrants at that time came from the Indian subcontinent, Africa or the Caribbean (the Commonwealth).

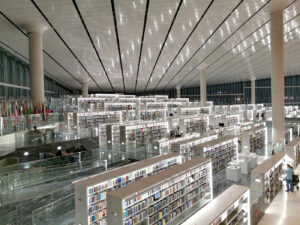

In 2015, while he was watching the flow of refugees from the Middle East to Europe, Michael was moved to begin researching his own family history. The resulting book, Lives Between the Lines: A Journey in Search of the Lost Levant, was first published in 2021. In his search, he discovered that the influx of refugees taking place today from East to West had occurred in reverse during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and that his own Greek and Italian Jewish grandparents had fled wars at home and found safety and prosperity in Egypt and Palestine under Ottoman, and later British rule. They lived in cosmopolitan, multi-religious communities and prospered at a time when the Suez Canal made Egypt the center of the world — a time when cities such as Cairo, Port Said and Alexandria were the equivalent of metropolises like Dubai or Hong Kong, London or New York today. Italian and French architects built homes, palaces and opera houses there, and the ruler appointed by the Ottomans was an Albanian.

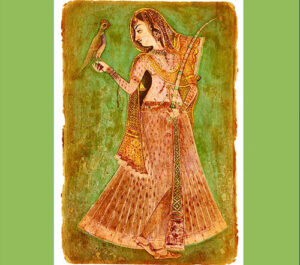

Egypt was a heaving cosmopolitan melting pot where Muslims, Christians of all denominations and Jews co-existed, each community thriving while collaborating in business and pleasure. Jews at that time and since their expulsion from Spain, before the creation of the state of Israel, were safer in the Middle East than in Europe.

The Ottoman Empire had mastered the art of blending religions, ethnicities and nations. Vatikiotis discovered that this system, cosmopolitanism, had been inherited by the Ottomans from the Byzantine Empire and before it the Roman, and had been created and initiated by Alexander the Great. No group was required to melt into the whole, but rather, each lived and thrived side by side, and this had been the norm for thousands of years. A strange thought, given that in the West today the idea of diversity and cosmopolitanism is being touted as some sort of European innovation.

His half Welsh, half Italian Jewish mother was born in Port Said, his Greek and Palestinian Arabic-speaking father in Jerusalem; his mother’s family was expelled from Egypt after independence and after the growth of the ideal of ethnically based “nation states.” An idea that had ironically evolved in Europe, particularly during the fascist and Nazi eras, where large numbers of non-ethnically or religiously compliant groups were expelled, most egregiously European Jews.

Michael Vatikiotis’ Greek-Palestinian, Eastern orthodox father left Palestine after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Suddenly the lines (arbitrary and artificial as they were) were drawn, and people who did not belong to one group became homeless “citizens of the world,” in search of a new home, new myths and stories with which to identify. But how could their stories of origin ever fit in with the stories of their new adopted homes? Would they have to forget in order to adapt, taking on their new nations’ myths and narratives and convenient half-truths?

One could argue that Michael Vatikiotis is an early version of the growing number of children born today in the increasingly multicultural west. Sons and daughters with a particular passport and identity papers, but whose emotional and cultural loyalties are divided between the country of their birth, their mother and their father’s countries of birth and even their grandparents.’

How can such children describe themselves? To whom do they owe their loyalty and allegiance? Should anyone be blindly loyal to any one nation? And if not, how can they function in a world defined by often blind “us and them” loyalties, especially during times of war and crisis?

A person of hybrid cultural identities like Michael Vatikiotis has the gift of seeing the same issues from a multiplicity of perspectives. That gift of seeing in the round is not one that nations in times of war want to encourage. In times of rising international conflict and tension, how does a journalist like Vatikiotis, who sees issues from multiple perspectives, manage to have a career? Trying to tell the truth in a world of media soundbites must have become increasingly untenable, and I wondered how he found a path where his skills of seeing and communicating on a variety of cultural planes could make a difference?

Is this why he was driven to write so many books of fiction and nonfiction, a longer, deeper form that allows for more nuance and expression of the in-between worlds, the liminal and uncharted? And how did he balance his work as an author with the world of politics, armed conflict resolution and private diplomacy, a path he has been pursuing since 2005 when he began working for the Geneva-based Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, something most writers would not manage to juggle with a prolific writing output.

Michael’s daughter Chloe and son Stefan with his wife Janick were born in Indonesia and educated in French schools. They now live in France and Singapore where their own children were born. Michael is the grandfather to children whose ethnicity and sense of belonging encompasses the entire planet and not one nation in particular. They are part of a new generation of hybrids growing in number that may bring the answers that the west in particular is still grappling with, after millennia of little genetic or cultural mixing with nations habitually perceived as “enemies” or “subject people.” Perhaps it is these hybrid children and grandchildren, born part “us” and part “them” who will refuse to live according to these old perceptions and will find the words and concepts for something new.

The Ideas Interview

Did you struggle to fit into the mainstream media when you started your career at the BBC World Service in London, and later became a foreign correspondent, and is this why you finally moved from the West back to the East, though not the Middle East where your ancestors had set up home, but further east: Indonesia, Thailand, Hong Kong and Malaysia?

I was raised in the Anglo-Saxon world, which is highly conformist. Not least because of the primacy of the English language. Once you have passed all the exams and achieved a certain professional status you are as good as integrated. So that’s why I felt a certain release when I moved to Asia. I felt I could embrace my identity as a perpetual outsider.

Being a grandson multiple ethnicities, do you pay a price for your inability to see the story from only one point of view, and is it no wonder that you have dedicated the second part of your life to armed conflict mediation, as well as developing a prolific writing career trying to bridge gaps in perception?

I have come to recognize that I bear all the personality traits of a classic Levantine — I can never really decide on my precise identity. At the same time, this endows me with the ability to see everyone’s perspective and point of view. This makes for an ability to easily forge rapport and trust, which is the key to mediation.

How can a writer or politician or diplomat of diverse background manage to express themselves, if their understanding of reality does not align with the narratives of the state in which they are resident, or the state media or governments they are working for? Are they not in danger of becoming the modern equivalent of the janissaries, or being used as pawns in a game against their own people, if they comply? Or be sidelined if they refuse to?

There’s always the risk of being instrumentalized as a journalist and even private diplomat. I believe that my complex identity insures me against this, because the different aspects of my identity are always arguing, which prevents me from landing on one side or another.

Do you think that writers, and policy makers and politicians of diverse background could hold the key to world peace, if their true points of view are given full expression rather than having to be censored and or/hidden, in order for them not to commit career suicide or be considered ungrateful or treacherous?

Idealistically speaking, the world could be saved by hybrids who refuse to be corralled into tribal or one-sided camps. Sadly, our world is dividing more and more. Polarization prevails and being a hybrid feels like being an outsider. On Israel and Palestine, for example, I can relate to the aspirations of Jews and Palestinians. But there is no middle ground on this issue. No one seems to be interested in a solution that finds a pathway that permits both Israelis and Palestinians to cohabit and mingle in a plural setting. You feel isolated and shut out because you can’t take a side.

Has the west become confused by the modern concept of identity, and do you think identity is being weaponized to highlight our differences in recent decades, in a sort of modern ‘divide and rule’? Is there an abuse of the term of diversity?

I was born into the Baby Boomer generation, which put a premium on the ability to succeed through one’s educational and professional ability and proficiency. I find it hard to understand the use of identity as a means of getting ahead of others, of establishing an exclusive right to a role or position. But then my generation is privileged and enjoyed more opportunity: today there are fewer opportunities, and identity has become a means of getting ahead.

Is there a sort of mock tolerance within western societies that is used to cover up deeper and larger scale crimes perpetrated on the world stage? And do you think the media and politicians can see the irony in their defence of tolerance at home for people whom they portray as enemies abroad?

There has been a decline in the overall influence of Europe and the United States, which has generated a reflexive defence of norms and values that were once considered universal, but which are now questioned in many parts of the world. At the same time, Europe and the United States have become much less tolerant places with the rise of anti-migrant sentiment that is fueling far-right politics.

In your opinion, why are the voices for war always so much louder than the voices for peace?

We have generally become immune to the effects of war. There was a period from the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s — almost two decades, during which we dreamt of the end of the war. In the three decades since, war has been waged somewhere almost perpetually. These forever wars are mostly in remote places from which people can feel a distance and disconnection. The technology used to wage these wars involves fewer people, more targeted strikes with the overall effect that even as civilians die in their hundreds of thousands, they seem like scores in a video game, somehow not real and not affecting us. This changed dramatically with the war in Gaza, which has etched the tragic human impact of warfare onto our consciousness.

Do you consider yourself more American than British, more Greek than American and/or British, more Italian, more Asian (after all these years in the far east), or something else?

I consider myself a classic Levantine: broadly a Canaanite, a hotchpotch of DNA flung around desert caravanserais mingled with that of weary Iberian Sephardic outcasts and wild Ottoman janissaries scything their way through the Balkans. I am neither a proper Jew, nor an observant Eastern Christian; a mixed heritage rooted in the historical blending of DNA and culture when there were no fixed boundaries across large swathes of the Middle East and Europe. Instead, there was a premium on cosmopolitan coexistence and collaboration. In Asia, my position as a sympathetic outsider has helped win trust and confidence among groups mistrustful of one another, creating space for a disinterested outsider.

How does your hybrid background help and/or hinder your career as a writer, journalist and diplomat?

Not possessing a singular identity is a great asset for promoting understanding of the other. It imbues me with a chronically malleable stance on almost anything, devoid of orthodoxy and always considering the context carefully before offering a view. These are classic Levantine characteristics, in which outcomes invariably depend on circumstances. The British novelist Eric Ambler described the Levantine mind as a committee always arguing over what to decide.

What drew you to Southeast Asia and what do you think that part of the world has to offer the rest of the world?

As an undergraduate I was drawn initially to the Middle East and studied Islamic History and basic Arabic language in Egypt and London. But I was somewhat repelled by the intractable nature of the region’s conflicts, and by my father’s dominant position in the academic field of Arab studies. So, I pivoted to Southeast Asia, learning two of its languages in university and conducting doctoral research in the region as a post-graduate. As I reflect on more than four decades in Southeast Asia, I think what the region offers the rest of the world is a narrative of social and economic progress overcoming ideological polarization, strongman abuse of power and profound inequality to emerge as one of the more prosperous regions of the developing world.

What are the main differences culturally and politically that you’ve found during your peace mediation work in Southeast Asia vs the Middle East?

There are profound differences in the nature of conflicts in the two regions. Southeast Asia is characterized by intra-state conflicts rooted in the struggle for autonomy and self-determination in the face of state-driven centralization and assimilation. In the Middle East, key conflicts are either rooted in deep enmity driven by historical grievances over the loss of land and identity, as in the case of Palestine, or communal cleavages and enduring inequality reinforced by autocratic rule. In Southeast Asia there is a greater receptiveness to dialogue and a willingness to compromise; in the Middle East there is almost no incentive to negotiate, reinforced by ingrained hatred and external proxy interference.

How do you balance your work as a diplomat, journalist and novelist — I mean how do these careers feed into each other, and how can you manage to be so productive in all of them, while traveling so much and raising a family?

I inherited a strong sense of discipline from my father, who hated to see anyone “wasting time.” His father had been a railway official for the Palestine Railway. Life at their home in Haifa was run with the precision of a train timetable. This was passed onto me in an intellectual context — reading and writing perpetually and managing to multitask effectively. No time wasted. My training as a journalist imbued me with a strong discipline to meet deadlines and trained me to write at speed. I find that the best way to write books is to plough on and never find an excuse to stop and reflect. I am often asked how I can manage to write and pursue my career. I always reply that if I had all the time to write, I would end up procrastinating.

Is there a figure in your life who has been a role model to you?

My father was a distant but commanding figure in my life. He died in 1997, some ten years after I had moved to Asia, so I missed the opportunity to spend time with him in later life. In researching my family’s history in the Levant and Egypt, I got a stronger sense of who he was and this has deeply affected me. Although ostensibly a scholar, he was deep down a committed activist. He desperately wanted to see a solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, though he never really wrote about it. I learned much later in life, only recently in fact, that much like me today, he positioned himself to offer good offices as a sympathetic insider-outsider to the conflict parties — both Israelis and Palestinians. He died three years after the Oslo Accords and would have been devastated to learn they came to nothing.

Why do you live in Southeast Asia?

Asia has a greater tolerance for ethnic diversity, even if there are conservative cultural peculiarities with regard to race and language. Historically, outsiders are regarded as an asset, natural intermediaries. There is no pressure to assimilate, simply to observe and respect cultural boundaries. Whereas what I see happening in the western world — partly because of misplaced notions of identity and guilt — there’s an increasing notion of color and race in the way people define themselves, even if it’s not a factor.

Do you consider yourself an exile from the West?

Not really. The longer I have lived outside the West, the more I realize that I am not really a Westerner and have embraced my hybrid identity.

What can the Middle East learn from Asia?

Primarily that conflict is too costly to sustain and all means should be explored to find a path to compromise and peace. Southeast Asia has not seen inter-state conflict in more than half a century. One reason is that all the states have created a regional framework for ensuring peace and security, despite the underlying tensions and prejudices.

Yet you have written that Southeast Asia has become the frontline for two of the most important global conflicts: the struggle between a declining West and a rising China, and another between religious tolerance and extremism? How do you see these conflicts panning out?

I see the possibility of a conflict between China and the United States, which will badly affect the Asia region — a likely flashpoint being over Taiwan. I believe the great religious divide has been somewhat neutralized by Saudi Arabia’s shift from providing support for Wahabi inspired Salafist movements in Asia. What remains to be seen is how the growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, increasingly aligned with Shia Iran, will play out in the region.

What are the half-truths that make it so seemingly impossible to build peace in the Middle East?

Primarily the fallacy that it is possible for Israel in its current political context to accommodate a Palestinian state, which allows Europe and the US to pretend they support a resolution of the Middle East conflict, while in fact, at best, the West desires containment facilitated by Israel’s unsurpassed military might.

Secondly, that Arab states support a peaceful outcome and resolution of the Palestinian issue, when in fact they thrive on and profit from outsourcing their security to external security partners and could care less about the Palestinians.

How do you balance your fiction writing with nonfiction?

Fiction is a great training ground for compelling and readable narrative non-fiction. Good storytelling starts with a fertile imagination and the ability to weave a compelling narrative without the benefit of fact or reality. I would feel less accomplished and fulfilled as a writer if I was unable to write fiction.

What advice do you have for writers, politicians, and diplomats of hybrid backgrounds like you? How can they use this difference to build peace, rather than add to the division? What skills of mind, attitude and communication do they need to work on?

The world needs people of hybrid identity to shore up the ability to understand the value of tolerance and diversity and avoid the complete takeover of humanity by tribal identity. As resources shrink and humanity struggles to survive, fear of the other is a growing determinant of behavior. As we have turned inward, so we have become desensitised to the suffering of others, which in turn has undermined the basic values of humanity. People with multiple reference points of origin and identity can help reinforce the understanding and empathy needed to preserve these basic human values.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

Most artists and writers are “claimed” by some kind of community. How do you contextualize your work when the fictions of identity have lost their spell?

That’s an important question. It’s very difficult for writers to be visible if their work doesn’t resonate with the collective unconscious of a particular tribe, unless they find a voice and theme that can transcend tribalism and express something universal and common to us all, but they must somehow not alienate the gatekeepers. Many skills required to achieve that. I will ask Michael to answer you.