Excerpted from the anthology Kurdish Women’s Stories (Pluto Press, 2020), by special arrangement with editor Houzan Mahmoud.

The Prison Speakers Played Islamic Verses

Kobra Banehi, also known as Kasnazani, was born in 1966 in the city of Baneh, in East Kurdistan (Iran). She narrated her story as a refugee in Germany, which was written down by Hatau and Paulien Bakker. Kobra lived in Baneh until 1978, when she moved to the city of Saqez. She studied up to the ninth grade, after which she was expelled from school.

The night I was born was also the night my three-year-old brother died. My mother was mourning. She refused to care for me, so my 13-year-old half-sister went around the neighborhood procuring milk for me or fed me sugared water to keep my hunger at bay.

My parents were tall and blonde; they were good looking people. My mother came from a good family, but my father, my mother’s second husband, was a Kurdish carpet maker and my mother was always telling him he wasn’t good enough for her. The only peaceful moments I recall from my childhood were when I listened to the radio with my father, Radio Taskant, from Russia. I would lay my head on my father’s shoulder and we would sit together quietly.

When I was almost five, my sister, who was by then almost 17, took me to a rally in the center of town. Sitting on her shoulders, I could see three men standing in front of wooden beams, blindfolded with their hands tied. All of them were Kurdish democrats. My sister brought me down just before the men were hanged. But the image of the three men standing there never left my mind. So, although my family members were not very politically active, I was aware of the injustices in my country from an early age.

In 1980, the regime brought down the Shah and held a referendum asking Iranians one simple question: whether they wanted to become an Islamic Republic. According to official results, 98 per cent of the people voted “Yes.” But in East Kurdistan, in the northwest of Iran, the story was more complicated: the Kurds had boycotted the voting.

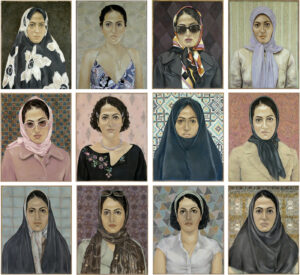

I was 14 when the protests began in my own hometown, the city of Saqez. The deceptive acceptance of an Islamic Republic through a referendum gave new strength to the Kurdish left-wing resistance movement, Komalah. Many Kurds were liberal Muslims, and mostly communist. I, like many Kurdish women, resisted the headscarf and the Islamic Republic it represented. I joined my schoolmates to discuss politics. My Kurdish teachers and neighbors always found the time to talk to me and my classmates about the revolution. Whenever there was a march, I would join in, no matter how cold it was or how far I had to travel. I was mesmerized by the feeling of solidarity, of being part of a greater movement.

The injustices at my school were readily apparent. The Persian teachers who were brought by the regime from Tehran wouldn’t greet their Kurdish students. They only talked to students coming from outside, who, as I noticed, were much better dressed than me and my friends. I started reading Marx. After school, I would go to Komalah lectures. I was fifteen; I knew it was forbidden, and yet I concluded: this is what I believe in. And for the first time, I felt I belonged.

My classmates and I started helping the Kurdish partisans by distributing pamphlets. When Komalah decided to retreat to the mountains so that the army would stop attacking civilians, my friends and I delivered food and cigarettes to the fighters and helped tend to the wounded — all without informing my parents.

I was expelled from school for ruining the decorations for an Islamic celebration by penciling out all the faces of the heroes of the Islamic Revolution. I started working full time as a nurse, handing out medicines and giving injections. I was 19, and I was good at my job.

In April 1981, the Revolutionary Guard of the Islamic Revolution, the Pasdaran, began its war on communism. All over Iran, thousands of communists were arrested, imprisoned or killed. The Pasdaran also attacked Komalah. As our solidarity protests grew, the Pasdaran began raiding Kurdish cities using armored vehicles, helicopters and bombs.

The shelling was relentless. I ran through the city, and stopped at a place that had just been hit by a rocket. I’d never seen so much blood. Saqez was turning into a ghost town. Many of the locals were trying to flee to the nearby town of Bukan when a helicopter fired at them on the road, killing scores of people. My comrades and I followed the survivors to Bukan. On the outskirts of the town, there was a small clinic with ten rooms. I moved in, and the group began to organize. People donated blood and bedclothes, and I went looking for ice. The girls made the place work like a proper clinic even though the oldest among them was only 24.

When Komalah surrendered after a month, the bombing stopped. My mother took me to my half-sister, who had married and was living in Tehran. She was hoping that I would forget the war and stay out of trouble. But four months later, when I returned to Saqez and school started again, it soon became clear that my life had changed forever.

Girls were forced to wear the chador, a long black veil that covered our hair and shoulders, when schools in the Kurdish areas reopened. At my all-girls school, we detested the chador; we had never even worn headscarves. We resisted our teachers, finding new ways to protest every day. During morning appeal one day we all shouted: “Freedom, equality, a worker’s state — we don’t want an Islamic Republic!”

The older girls protested for a week when one of the last Kurdish teachers still working at the school was fired. During the commemoration of the establishment of the Islamic Republic, all 200 girls sang our song of freedom in front of government officials, to the tune set by the violin player. Some of the girls were expelled but we only became more determined because of it.

I started distributing flyers for Komalah, keeping this hidden from my parents. As few people as possible were supposed to know what I was doing because underground work was not without risk. The Pasdaran were constantly on the lookout for Komalah members. In 1983, a hundred of them had been rounded up in a single day. Under torture, most gave up others’ names. Komalah was rapidly losing members.

As a little girl I had heard of grown men who had lost their minds in the torture chambers of the Shah. I was sure that I would suffer the same fate if I were to be captured, but it was too late to turn back now. Komalah needed the women in the towns and villages to supply their fighters with food, medicine and information. They were only allowed to flee into the mountains if there was imminent danger. But, as more and more comrades were tortured and more names were given to the Pasdaran, more women also fled into the mountains. Komalah asked its members if they felt the women in the mountains could pick up a gun too. “Of course,” my friends and I said. “Give us weapons.” And so, Komalah became the first Kurdish-Iranian resistance group that had women fighting as well, and I was proud to belong to them.

One day, I felt a shadow following me. I told my neighbor and she warned me to be careful. “But I haven’t really done anything,” I said, more to calm my own nerves than anyone else’s. The next day, the shadow disappeared and I thought it must have been a figment of my imagination.

Two days later, a man came to my clinic and asked if I was Kobra. He was a clean-shaven Persian man in his thirties. “My brother is ill, will you come with me?” he asked.

“Why me?” I replied. “There are so many you can ask.”

“No, we have asked around and your name came up.” He wasn’t the first to ask for me specifically, and so I joined him.

When we reached the street, I saw an ambulance waiting for me. That was not a good sign. Two men came out of the car, one wearing a full beard. They opened the door and told me to get in.

“What are you doing to me? My parents don’t know where I am.”

“Be quiet, the game is over,” one of the men said. He blindfolded me, and the ambulance drove off. I tried to think. Who could have betrayed me? Three weeks before, a boy I knew had been captured and was released soon after, but I had not been in his unit. Did he even know I was working with Komalah? Then there was a girl from school who had been captured — it must have been her. How could she do this to me?

I had distributed flyers, written slogans on walls, and handed out medicines and food to fighters, but I had never carried a weapon or used any violence. Still, it was better to keep quiet.

The ambulance stopped and they dragged me into the Pasdaran office. In the hallway, girls in black chadors were standing with their faces towards the wall. Were they Pasdaran? I was taken to the end of the corridor. A man walked up to me and asked: “Do you know Komalah?” I smelled the nicotine in his breath. “I have heard of them,” I said, avoiding his stare. The man hit me and my head smashed against the wall. For a moment I thought my eyes were going to pop out. It was only the beginning.

I was taken to a torture chamber in the basement. I could see chains hanging on the wall and a metal bed with a black top. The man told me: “I will make your life as black as the top of this bed.” But instead of beating me, they took me back upstairs into a cell.

A girl was already there when I entered. “Why are you here?” the girl asked. She wore a chador, just like the girls in the hallway, but hers was completely closed.

“I don’t know,” I answered. “They brought me here.” Something was wrong with this girl. The closed chador, that was a sign of conviction.

“How many were you?” the girl asked. “I don’t know,” I replied. “I was alone.”

Two hours later, the girl was summoned away. Then they came for me and led me back into the torture room. I had to squat with my face towards the wall. The man asked me: “Have you made your decision?”

I didn’t answer.

“Have you decided to talk to us?” the man asked again, staring at me.

I kept quiet.

He gave me a paper. “Write down your confession here,” he said. “Did you work for Komalah?”

“No,” I said.

He slammed my head against the wall. Blood started to drip from my nose and mouth. And then his fists and his feet were hitting me over and over again. My blood only seemed to infuriate him more and there was no one to stop him.

In the early morning, I was taken back to my cell. Whenever I tried to sleep someone clanged on the metal door to wake me again.

The next day I was brought in front of a mullah, the Islamic cleric, to be officially sentenced. “Should we use coughing syrup or the needle?” someone asked him. These must be the names for their torture methods, I thought. Were they trying to scare me?

Once I was back in prison, two men took me to the torture room, strapped me onto the metal bed, and tied my feet. “What is your shoe size?” one of them asked while the other placed a bucket under my feet.

“When I’m done with you, you’ll be a size 46.” The man grabbed a cable from the wall.

I listened to Islamic verses being recited through the speakers. I couldn’t move, and deep down I knew what was coming.

The man raised the cable and started whipping my feet. They cracked open, blood flowing out. Sometimes he would hit the wall instead, but after a while I was no longer able to tell the difference. A lump of flesh landed on the wall — a bit of my bloodied foot.

When the men left the room, I looked at my feet. They were black and swollen. See, this is me, I didn’t talk. My feet have accomplished it. They had called me a mule. Yes, I was as stubborn as a mule.

Throughout my ordeal I had refused to scream. I didn’t want to give them the pleasure. But now I realized that if I did not scream, they would beat me to death.

The next day they strapped me onto the metal bed again. One sat on my back, the other hit me, asking me the same questions over again. Had I worked for Komalah? Who did I work with? “I have nothing to say,” I kept saying. “I have sympathy for Komalah, but I never joined them.” Eventually, I lost consciousness.

Two prison guards dragged me outside and laid me down in the snow. I couldn’t walk anymore. The pristine white slowly changed into a crimson red. I didn’t mind the cold. After months in darkness, I was finally able to see the sky again, free for now. I was nineteen and my body was broken. My swollen, bleeding feet could be seen from afar. Prisoners stared at them, a cleaner saw my feet and would tell my parents I was in prison — my feet made me famous. They became an icon of my determination and endurance.

One of the guards untied me when I came to. “Why don’t you talk? They will kill you,” he said. They kept me in the torture room for two weeks and kept beating me. Every half hour someone would knock on the metal door. I could hear screams coming from other torture rooms. Young men, crying for their mother, “Daya!” The guards took turns beating me. Once, when I was alone, I looked at the cable and wondered if I could use it to end my own life.

One night I heard a familiar voice. It was my school friend, the one who had likely given me up. If I talk, this will happen to others as well.

I was given an injection — if it contained something or was just meant to scare me, I’ll never know. Later, a guard told me: “Do you know the Caspian Sea? We will take you out on a boat, shoot you and drop your body in the water. Your parents will never know what happened to you.”

I didn’t bathe for two months. One day, a girl asked me if I was Kobra and then took me to the showers and bathed me. The girl took her time to softly wash every part of my maimed body.

Just when my frail body was about to give up, the torture stopped. I was summoned up again. I couldn’t walk anymore, so I dragged myself up, half sitting down, step by long step. In the corridor, I passed a man who had both legs in a cast and, like me, used his buttocks to move. I looked at him. If they tortured me to this extent, what did they do to the Peshmerga fighters they captured?

For four months, I stayed alone in a windowless cell. Sometimes, the lights were on for twenty-four hours; at other times, they were off for just as long. It was impossible to say if it was day or night. The only interruption was the midday meal. My cell had no water and no toilet, but I was allowed out to the toilets and the showers twice a day. I stopped having my period, a good thing considering other girls had to make do with newspapers. I started talking to myself.

After five months, my mother was finally allowed to see me. I saw her walk towards me. She started screaming: “She is not my daughter! What did you do to my healthy daughter?” I hadn’t seen a mirror in months. I looked at my mother and yelled: “Here I am!” My mother started sobbing and I realized that I had changed.

I was sentenced to two years in prison and placed in a bigger cell with 19 other girls. I had grown used to being alone and didn’t trust anyone. That was the worst of all: being around others but not daring to speak. Only three of them, I reckoned, had kept quiet. Most had a tortured conscience. It’s not so easy. You go into prison as a human being and when you come out, your body has been broken, along with your morale and your soul.

The prison was bombed by the Iraqi army during the Iran-Iraq War. Three girls were killed. It was frightening, but at the same time it didn’t matter, I was no longer afraid of death.

By the end of my sentence, the director of the prison insisted I should give an interview to the Iranian state television to confess my guilt. I refused. I had been in prison for over three years by then. He told me to write that Komalah was a traitor of the people and that I would have nothing to do with them. I refused again.

They kept me for another five months. Finally, they sent for my father and asked him to bring the deeds to our house. If I was caught again, they warned, my family would lose their home. I saw my father in the courthouse. The mullah said he knew my feet had not yet healed. “What will you say when anyone asks you about that?”

“That I was tortured,” I replied.

My father winced and apologized to the mullah. The mullah looked at me. “Who tortured you?”

I said: “You. The Islamic government.”

The mullah turned to my father and said: “Look at her. We were right to put her in jail.” My father whispered to me as we were leaving the building: “Please, never again. Watch it.” But when I looked at him, I could see that he was proud. I was welcomed back as a hero in my hometown. I was one of the few who had resisted, and that lifted everyone’s spirits. The thing is, the Islamic God is so punishing and narrow-minded, it just didn’t appeal to me.

After my release, I tried to live and went back to school to complete grade 10. I worked in a shop in Saqez, but the intelligence service pressured the shop owner to sack me. Later, I moved to Tehran and worked there. Tehran is a huge city; it was slightly easier to find a job under a different name.

I am 52 now. After the torture and continued pressure from the regime, I moved to Germany. I’m an exile here. My body has never fully recovered. I work voluntarily with refugees and youth. After all these years, it’s still not easy to talk about that time. All I can say is that I saw the regime’s true face.

Kurdish Women’s Stories editor Houzan Mahmoud is a Kurdish feminist, public lecturer, and co-founder of Culture Project. She is the winner of the 2016 Emma Humphreys Memorial Award and the 2018 One Law for All Secularism Award. She has been published in The Independent, The Guardian, and New Statesman. She resides in Bonn, Germany.