In Mai Al-Nakib’s new short story, a woman makes a Herculean effort to preserve the memory and artwork of her late husband.

Mai Al-Nakib

Meraki-mou, take better care of your swan’s neck. I thought it was the delirium of dying. I had never seen a living swan in my life. With more energy than he had mustered in weeks, he jerked his head right off the pillow. I leaned over to reposition it, and he pressed his face against my neck, his eyes jelly-cold. He repeated what he said, then slumped back down. His final words a command to take better care of my neck.

That was ten years ago.

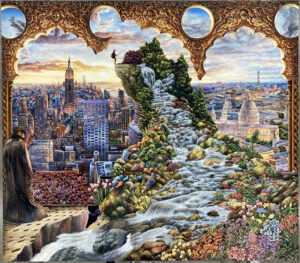

I would rather he had instructed me on what to do with his fucking work. His paintings climb the walls of my apartment, sullen stacks of oversized canvases closing in. I can slap cream on my neck, but what do I do with his avalanche of paintings?

I am tempted to dump them into the sea.

Overnight, Theo was in pain; inside a couple of months, he was dead. By then the girls were in their late twenties, tracing the path of their lives. The funeral arranged itself, like a library. I don’t remember who came or what people said. I only remember focusing on not crying, because sorrow, like dreaming, is private.

The day after Theo was packed tight in the ground, the calls began. His agent, then a few gallery owners. They were sorry, they said, so sorry he was gone, and then they asked where I wanted his paintings sent. I didn’t get it. The paintings were the paintings, with or without Theo, and, to the extent that I understood anything about the art world, death could only add value. They agreed, but the calls kept coming. Later I would learn that his paintings had stopped selling, that he had kept it secret from me.

They arrived from all corners of the earth. Every doorbell announced another one. I wept and moaned as I signed countless DHL slips handed to me by embarrassed deliverymen. By week’s end, the paintings had piled up to the ceiling. I stared in bewilderment at the tower in the foyer. His studio contained at least four additional stacks. His office at the Athens School of Fine Arts, more still. I anticipated other paintings would arrive over the next month as news of his death spread.

The only solution was to put them in storage. My tears dried up, and I spent the next few weeks lugging canvases from the apartment to a large, rented storage space on the outskirts of Athens. Once the apartment was cleared, I moved on to his studio, back and forth. Then from the studio to his office, with its wall of steel cabinets full of endless sketches in labeled folders and hundreds of notebooks arranged by spine heights on shelves. I must have entered and exited that storage space 1,000 times. Lit by a dim bulb dangling from the high cement ceiling, thin shadows fringed my memories as I worked. Scuttling in and out of that place was a version of grief. Remembering all the things, then forcing myself to forget. I terminated the lease on his studio and handed his office key to a shiny young artist singing his condolences as he sped past me.

A few months later, I packed a suitcase and persuaded my girls to come with me to Iceland in the vortex of winter. An outside that I imagined would be an extension of my inside. They agreed to come because I was paying and because they were, they explained, not happy with the way I was handling their father’s death. Their father. Their father had spent hours each day painting, and when he wasn’t painting, he was walking. It was a religion with him. Up and down the hills of Lycabettus, Parnitha, Pentelikon, and when wild brush and trees were scorched by arsonists, he found other hills to climb. He was working, he said, painting as he walked. I never did any of that because our two daughters were on me. They tucked themselves into warm corners of their shared bedroom, mostly raising themselves. They owe me nothing. They owe him even less.

In Reykjavík, I walked out onto a frozen pond for the first time. I could feel the water sludge under my feet, despite the thick layer of ice between my soles and the flow. That dark gray liquid was death. It’s where Theo was. I was shuffling on ice, but I couldn’t make out any difference between Theo under it and me on top. It all seemed part of the same gray mush. But even as I was having that thought, I knew it was more Theo’s than my own. Under and over were opposites, not at all the same. Theo was embedded forever beneath the mercurial light and dark of an Icelandic winter morning. I was still in the thick of things, like the swans gliding across the slice of pond where the water was kept artificially warm for them in winter.

Every year since, always in winter, I pack my bag and head to unfamiliar places to get myself lost. Peru, Nepal, Morocco, Zanzibar. Sometimes with the girls, more often alone. A month each year. That’s something Theo and I never did together. We were always working. Art is work. The fantasy of art as celestial inspiration and flapping around a studio — that isn’t it. There was no room for family travel, no time to pause.

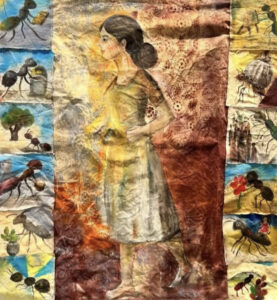

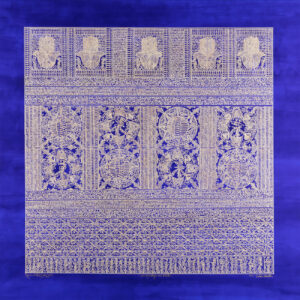

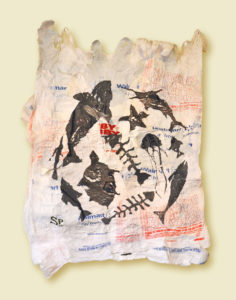

I still paint his designs on my ceramics, organic shapes suggestive of primeval life, of scrawls on cave walls. There’s no getting away from him, everywhere I turn. Even after ten years, his lines still mark my clay.

When we were together, it was like being burned alive. Right away he called me Meraki — creativity and soul. A month after we met at art school, he asked me to go with him to Koufonisia. In those days, a deserted island was a deserted island. We spent two weeks naked under the sun. You belong to me, Merkai-mou. I remember holding his hands up to the sun, thinking how transparent skin was, like porcelain. As the sun set, bats replaced gulls, and he would build us a fire on the beach. Tree shadows slunk across sand like sharp bones. It was a prelude to the life we were going to share.

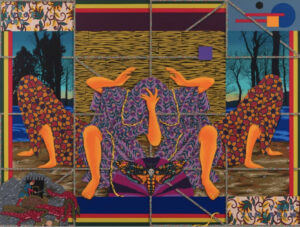

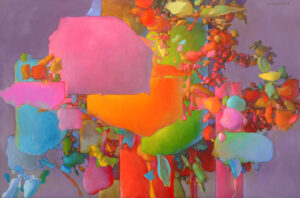

Nikos Dimou says, Man longs for immortality. Whereas the only thing he knows for certain about the future is that eventually he’ll die. So what do we do? Dimou says that the artist fills the gap between desire and lack of fulfillment with forms. Theo was obsessed with death. A long series of his paintings are of aging skin. Putty-colored crevasses over massive canvases like networks or constellations. Stand far enough away and you might make out a hand or neck or breast; step forward again and the less troubling patterns and trails reassert themselves.

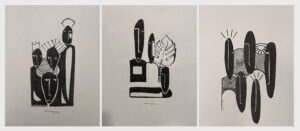

When Theo was a boy, he had a nanny he adored. He spent more time with her than with his own mother. Evangelina seemed old to him when he was little, and of all his nightmares, her death was the most terrifying. She was only forty then, but compared with his young and exquisite mother, Evangelina seemed ancient. Theo used to pray each night for his beloved nanny not to die in her sleep. He invented covert strategies to keep her alive. One of those strategies involved making drawings of women who looked even older than Evangelina. Women with crinkled skin sagging off their skulls and joints. He was seven, maybe eight, when his peculiar obsession with wrinkled skin started. Small squares of paper scratched over with ballpoint blue. Nobody could tell what they were. I still have them. They were filed in one of the cabinets in his office. He filled his life with forms to stave off mortality. And Evangelina? She lived past a hundred. He died before she did. His mother died before her, too.

There’s another way Theo filled the gap between desire and the impossibility of satisfaction. We were young. It happened then, and it happened long after we were young, always with women younger than himself and me. We were not moralistic. He was free, I was free. We must have been jealous, but we would never have admitted it. It became more difficult as I got older. Forty may be the new thirty, fifty the new forty, but that’s not how it was when I was forty and fifty. His line of willing women never shortened, but I didn’t have the equivalent in men. Men are mean that way. All they see is the neck sagging or about to sag. Even almost-dead men, apparently.

A carpenter has spent the last month at my place building vertical shelves for Theo’s canvases across every available wall and corner, shelves that cover up even the largest windows, leaving me only a sliver of access to the balcony and almost no natural light. I’ve gotten rid of many of my own things to accommodate his work.

I can no longer afford to pay for the storage unit. When I first rented it — almost as large as our apartment — it was supposed to be a temporary reprieve so that I could figure out what to do. That storage unit cost more than half my monthly income. For ten years I’ve been storing Theo so that I don’t have to deal with the burden of his inheritance. But I no longer have a choice. I’ve hardly saved a penny. Art pays only the few. I suddenly understand what my girls have been squawking about, why they have become so critical of my annual trips.

I’ve spent the last week moving all his work out of storage and into my apartment, reversing the actions of ten years ago under the flickering light of that swaying bulb. A carpenter has spent the last month at my place building vertical shelves for Theo’s canvases across every available wall and corner, shelves that cover up even the largest windows, leaving me only a sliver of access to the balcony and almost no natural light. I’ve gotten rid of many of my own things to accommodate his work. That wasn’t hard. There is pleasure in ruthlessly clearing out what starts off important and, over years, transforms into clutter: clothes that no longer fit, accumulated kitsch, my daughters’ toys, books I’ve never read or won’t reread, chipped china, dented utensils, forgotten mementos, cassettes and video tapes, reams of paper I couldn’t bring myself to sift through, pillars of faded pink folders. My heart hardened, and I tossed it all away. I felt light until the carpenter arrived. Vertical storage shelves, floor to ceiling. Sawing and pounding and sawdust in every crevice. I escaped to my studio while the man reshaped my walls.

Theo is now the membrane of my apartment. My apartment. It’s the apartment I chose for us in Kolonaki forty years ago. He paid for it with paintings commissioned by Swiss banks, but it was the space I chose. The tall windows let in rose-gold Athenian light. The wraparound balcony was where I went to breathe, away from him and the girls. I was the one who had selected the furniture from a hidden gallery off Monastiraki, mid-century pieces out of sync with the eighties. Theo didn’t waste a second making decisions that, ultimately, he would insist, mattered not at all. In the end it was my saggy neck that mattered. My droopy, unswanlike neck. Not the loft, not the light, and most certainly not the lounge chair and ottoman buried under rolls of artwork that do not slide conveniently into vertical shelves.

No museum or art school or library will have it. He’s not that kind of famous. People forget. He garnered some attention, but it’s been a decade since he died. In the last five years, I’ve organized three exhibitions of his work at galleries here in Greece. Not my work. His. I managed to sell a few pieces, but attention spans are short and seem to be getting shorter. He’s no Kessanlis or Caniaris. In a few years, who will remember? A lifetime of energy expended, a mountain of production, and none of it wins him immortality. After I’m dead, after his daughters die, he will be forgotten.

You are a woman from another time. My daughters say that to me. They may be right. It is terrible to love a man more than he loves you. Then, for the rest of your life, to continue to love him that way. Even after he’s dead, to go on as if nothing much has changed because, if I’m honest, not much has.

But they may be wrong. I didn’t chase after fame. I did what I pleased. I wanted to work with my hands, to inhabit landscapes and weather through color and clay, to ground myself. If people liked what I was doing, well and good. If they didn’t, that was okay, too. Attention, like money, is a kind of filth I wanted nothing to do with.

Theo did.

I don’t normally look like this, frizzy hair, unmade face. It’s been a crazy month.

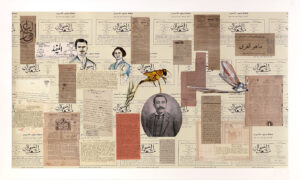

In my studio, I keep an envelope of photos along with brochures from my past exhibitions. They are warped, damaged by a flood in our basement six years ago. The basement is shared by all the owners of apartments in my building. Each of us gets a taped-off square of space where we can heap boxes as high as we can manage to balance them. The flood was unexpected. Not rain, but busted pipes, a vile mix of rusty water and sewage. It hadn’t been prudent to store our lifetime of photographs down there, but I couldn’t bear to keep them in the apartment with me. I had stashed them in shoeboxes after Theo died. I deserved to lose them. The few that survive intact happened to be in a zippered plastic sleeve. Someone had taken some shots of Theo and me in Paris, side by side on the curb outside the gallery where we were setting up his exhibition. It’s late. I’m smoking a cigarette. The images are blurry, but in one of them, we’re grinning widely at each other, our feet pointing in the same direction. What I wouldn’t give to remember what we found so amusing.

Tucked between those photos in the plastic sleeve were a few of my early brochures that used my favorite headshot. Look at me! Twenty-seven years old. It shocks me to see my young face. I’m a stranger to myself. The truth is, I don’t feel different. No, that’s not true. I do feel different. Everything is different. He’s dead, and I carry the weight of his legacy. That kind of responsibility ages a person. I had sharp cheekbones and wore my black hair long, with blunt bangs. My dark eyes spell trouble in that photograph, the kind of trouble some men found irresistible. Theo was right: my neck is as long and slim as a swan’s. It felt like the whole world was mine. But the world proceeds without paying attention to anyone. I find this planetary indifference soothing.

I take reasonably good care of myself now. I didn’t when we were together. Too much to do and still young enough to take elasticity for granted. I’m no fresh cygnet, and I don’t look anything like I did in that headshot, but I don’t normally look as bad as I do today, roots showing, face exposed. My poor, ravaged face — unavoidable extension of my neck.

He’s gone, and I hold his forever in my hands. In the process of disposing of so much to make room for the shelves to store his canvases, I daydreamed about adding those canvases to the growing mound of junk. He saved every sketch, every scrap and note. All of it archived. The pink folders I threw away didn’t belong to him. They were mine: notes for my projects and exhibitions, folders full of my children’s drawings, report cards, invitations to summer plays they staged on the balcony when they were small. I am a demon. I shoved it all into black trashbags and dropped them into the dumpster two neighborhoods down from mine. I didn’t want to be tempted to retrieve anything in the middle of the night. But his notes, his sketches, his scraps — I saved all of it.

One especially aggravating morning, I crumpled a sketch he had done of me into a tight ball. I held it in my palm for an hour, trying to convince myself to throw it out exactly the way I had been throwing out everything else over the last month. I couldn’t do it. The sweat of my palm made the thick paper feel like leather. I unclenched my fist and smoothed out the sketch on the marble table, placed it back in the folder he had labeled MERAKI. How could I throw it away? It had my name on it. In that moment, it felt as if he had just died, and like we had just met. Meraki-mou, your neck. Meraki-mou, you belong to me. Time has me tangled up. The future has been stored for ten years. Now it’s here, and I think I’ve made a colossal mistake.

I put this burden on myself. Everything moves fast and I remain slow as clay. Where do I offload it?

Into the sea.

I don’t care about much anymore, and I’ve become incapable of pretending I do, which makes me a less social being. It’s the privilege of age. To care less, to pretend less, to be only as genial as it suits me to be. The company of my old friends, I find grating. The company of strangers, intolerable. The world is spiraling out of control. The plastic bothers me more than anything. I don’t eat fish anymore. I read somewhere that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea. I won’t be around, but it’s coming.

The vertical shelves are installed and filled. He has been contained, but at a price too high. My daughters refuse to step foot in the apartment, tell me I’ve lost my grip. I glance around my darkened space. The smell of raw wood inflames my lungs, keeps me from sleep. Only the “now” has the value of “forever.” Theo never read Dimou. He should have. Those were Theo’s wrinkles, not Evangelina’s, not mine.

Canvas is not plastic. It is not of this century. I could sink him into dark water now, my footsteps crunching forever the ice between him and me.

This is the best I have read by Mai Al-Nakib. Captivating.

It’s so real! I feel I share so much with Meraki-mou, not only her bewildering style but even the swanlike neck. Thank you Mai for feeding me with this amazing story!