Noreen Moustafa

As my father’s chronic health issues started to catch up with him, there was a slow peeling away of the life he’d built. He’d spent the last year in a converted residence called a “board and care,” akin to a nursing facility except there weren’t any actual nurses. Just underpaid caregivers who in fact, couldn’t care less. The unmarked house on a tranquil, suburban street of the San Fernando Valley looked like the kind of family home any immigrant would be happy to end up in. But it wasn’t. Inside were five or six very sick people, each separated from their families who could no longer care for them. And when I visited, I found its white picket fence ironic and utterly heartbreaking. My dad was falling through the cracks of the very systems he exalted, though he would never admit it. He was “too rich” for government assistance but “too poor” to pay privately for the level of help he wound up needing. Yet he bore it all with true American grit and the spirit of rugged individualism he admired. He never complained and rarely asked for help. He contentedly hung in this balance for a long time. As long as he could watch the news, talk to me everyday by phone, and got sugar-free cookies delivered every now and then, he insisted he was fine. For him, the dream continued.

But when he also lost the ability to fully extend his fingers it became harder for him to use his phone. He also had some lingering delirium from his most recent hospitalizations, which were becoming alarmingly more frequent. The television became harder to follow. And even when the coast looked clear, a cloud of confusion always threatened to come over him. Especially when he was alone, which was almost always these days. After his retirement, he slowly lost touch with his colleagues and saw friends less and less. And when he became handicapped, he couldn’t just drop into the flow of the city that had long been his companion, to people-watch or chat someone up.

“Nor, Nor. Sweetie, sorry to bother you, I need your help. I can’t log into my Kaiser account. It’s all locked up. Jojo here says I’m missing a prescription for three days now. Shit. This button…”

“Daddy, what do you mean? You can’t miss your medications for three days! They didn’t refill it?” Feeling so far away and helpless on a transatlantic call, I was furious.

“I don’t know, I pressed too many buttons. I can’t remember my password. I tried Noreen123, Noreen321…everything. We need to send a message to the pharmacy on the website.”

“A message? I swear I hate Kaiser — why can’t we just call?”

“Noreen, Kaiser insurance is great. If I lived in Egypt, I’d be dead by now,” my dad laughed, trying to keep things light.

“Ok, I’ll figure it out, daddy. I’ll reset your password and call you back. Don’t worry.”

“Thanks baby, I’m sorry. I love you.” His voice dripped with humiliation.

Even though I was now living on another continent I was a part of the daily charade that everything was okay, when it clearly wasn’t. I opened my laptop but for a moment was paralyzed with sadness. My capable father was receding each day. I shook myself out of it and launched into the familiar yet dreaded “Forgot password?” procedure. Mother’s maiden name? Got it. Birth date? Sure. Last four of his social? I knew that, too. But the final question…what is your dream job? Really? This was a security question? Seemed so deeply personal. I knew that if I answered incorrectly, it would only deepen the mess he was in, so I thought hard. And then almost instinctively, I typed in “engineer.” And when the green checkmark indicated that I had answered correctly, I let out a sound that was equal parts laugh and cry. His dream job had been his actual job! I just loved my daddy so much, I thought, as tears clouded my eyes and streamed down. Of course, he didn’t pine for a dream job he never pursued. That just wasn’t him. He had lived his Los Angeles dream.

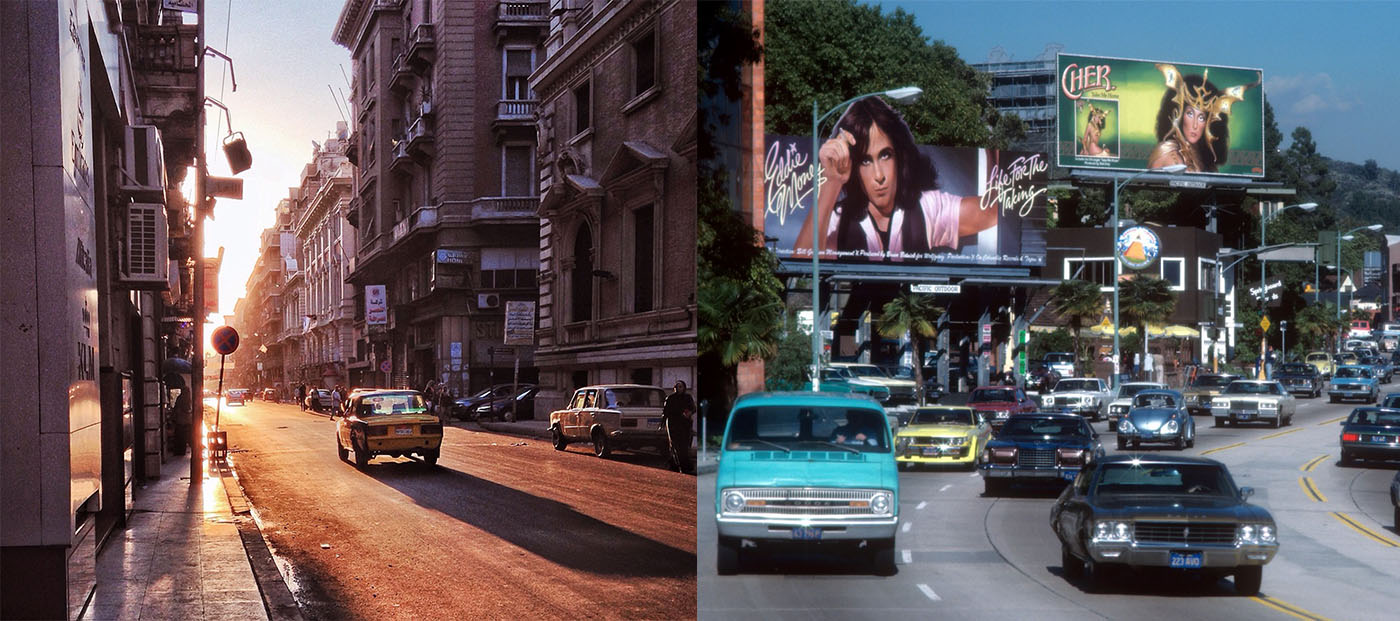

Growing up in Alexandria, Egypt my dad lived in an upper middle-class, cosmopolitan neighborhood called Smouha. He recalled vividly one neighbor in particular — an American diplomat with a proclivity for bubble gum, Bazooka bubble gum. Who knows how this man obtained a limitless supply of the classic confection but my dad said that this envoy of the US would often pick up the young neighborhood kids and take them for a joyride. He would hand each child a piece of gum, almost like a ticket to board, as they clambered into his Cadillac convertible. The kids were ecstatic, blowing bubbles, giggling, and bopping to Chuck Berry or Elvis Presley. Turns out, American soft power comes in many forms including this saccharine pink delight. My dad was enamored with this character, and it was in his boat of a car that he was first sold the dream that is America. Bazooka bubble gum with its red, white and blue wrapper is quite hard at first, then softens. Suddenly succulent and delicious, it very soon after becomes completely void of flavor — perhaps the perfect metaphor for how so many see the American Dream now: artificial and disappointing.

But not my dad, who held onto a gilded view of Los Angeles over the forty years that he lived there, no matter what life threw at him. It was a different time when he arrived in the late ‘70s. Patriotism and love of country hadn’t been coopted by the right yet and immigration was high, generally welcomed and facilitated. Though we were exoticized and just hounded by that Bangles song (you know the one) my dad made integration look easy. Despite often mixing up his “b’s” and “p’s” — a common pitfall of native Arabic speakers — he never let his accent get in the way of his liberal use of American idioms and slang. Growing up, he was constantly embarrassing me by high-fiving people hello and ordering “Diet Bebsi and bobcorn.” He didn’t burden himself with duty to claim roots or to enlighten the ignorant. He just wanted to be free and being American did not feel complicated to him as it sometimes does for me.

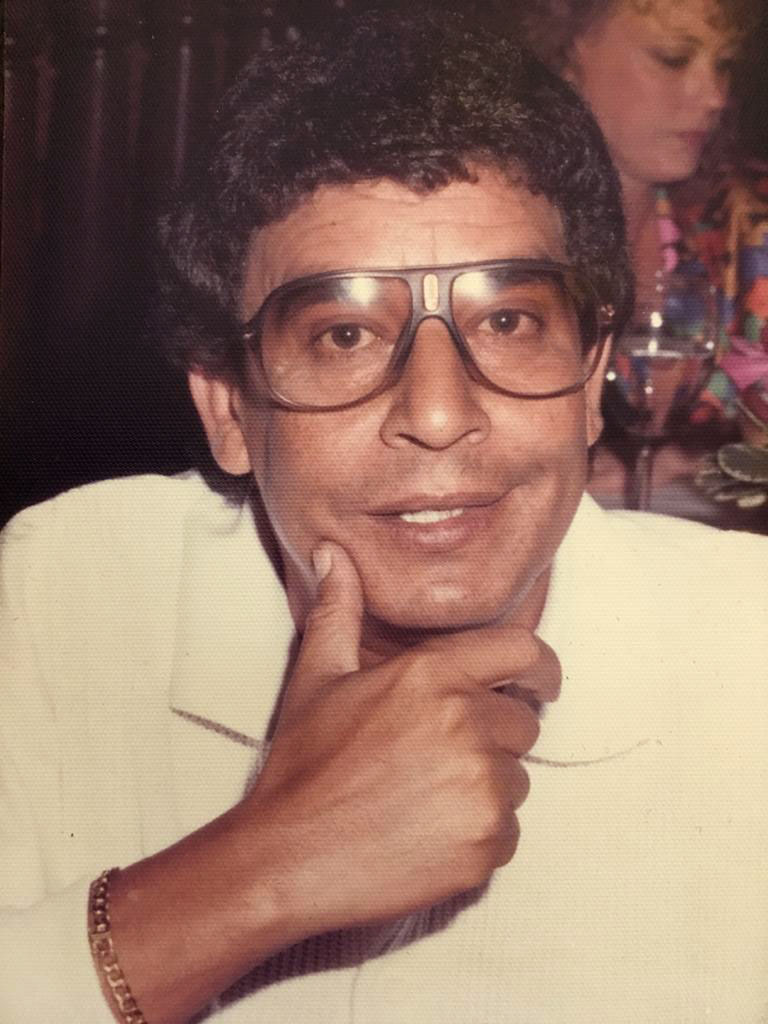

My dad always hated his name, Mahrous, even while he lived in Egypt. He said it was ballady, low-class, showing how much he had internalized the rigid stratification of Egyptian society. He was the eighth of nine children. And with a laugh, he told me that his parents never even bothered to find a name for him when he was born. Instead, on the way to the hospital, my grandfather asked their bawab (the doorman) to choose one. I think my dad was relieved when he was rechristened at work with his anglicized name, Ross. He didn’t find it xenophobic or racist. Ross was just who he was and perhaps, whom he had always wanted to be. And he had to come to Los Angeles to become him. That is why for me, forever the two, the man and the city are inextricably linked. So much of what I love about my hometown of LA comes from my dad’s view of the city of his dreams and our ritual weekend drives. But as a second-generation American, more sensitive to American society’s shortcomings, I could see things that he couldn’t. And since his passing, I have been questioning which of us really saw my dad’s LA story for what it actually was.

Just as my parents did, I eventually left the city where I was born, ostensibly for work but ultimately for adventure, love, and a desire for self-actualization. But unlike them, I ended up somewhere that wasn’t on my radar at all — Italy. Conversely, my dad’s goal had been fixed for years. It had to be LA, as it has to be for the many bold dreamers who seek to make a home there just so they can be themselves. (And avoid winter completely, of course.)

Los Angeles is at once the manufacturer, dealer, and consumer of a certain dream — the intersection of endless possibility and equal opportunity. An illusion projected all over the world and then self-reflected back onto the nation itself. And it is in this reflexive turn that the American dream is perceived as real, when the manufacturer forgets the origin of his invented product and actually comes to believe in his own creation. My dad’s believed fantasy was that he was all American, full stop. No hyphens. No complications. No questions. When we would both eventually experience discrimination down the road, it ran so counter to my dad’s initial immigrant experience, he had a hard time recognizing it.

I remember telling him about a job interview I went on, shortly after the invasion of Iraq.

“Baghdad? I don’t get it, why’d he say that?” My dad was puzzled.

“Daddy, that’s what he said. He was looking at my resume, read my name out loud with an accent and said, ‘Where’d you grow up, Baghdad?’”

“So, what’d you say?” The look on his face changed.

“I said I grew up one mile from here, on Elm Dr. in Beverly Hills.”

“What an idiot, doesn’t he know this is America?” my dad protested.

Somewhere along the way, our perspective on the promise of America had diverged. Because even when he did get it, he thought of it as an aberration, an exception. He had so fully embraced his new country, he just didn’t have any room for detractors of the dream or even for his former identity.

The times when we were together in Egypt were few and I remember him against that backdrop mostly as a misplaced item. Though he was born, raised and educated in Alexandria, he just didn’t belong. Serving in the army and going through a harrowing experience as a prisoner of the ’73 war with Israel did not increase his connection to Egypt. It motivated him to take responsibility for his own life and he moved to Saudi Arabia for two miserable years to earn enough money to emigrate. Everything that came after was the payoff. Driving his convertible in Santa Monica, wearing a white Fila jogging suit, aviators on, smoking a Benson & Hedges cigarette, his combed-out curls shining in the sun — that’s where he belonged. In this portrait in my mind, he embodies the time and place completely: 1987, Los Angeles.

My dad had been a civil engineer with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power for over thirty years. He worked a few odd jobs upon arrival as a new immigrant, but it didn’t take him long to start a career in his actual field of study. Working for the city meant that he had good benefits, general job security and he was so proud. He was not exceedingly accomplished but he was a fulfilled man, and probably the most contented person I have ever known. As much as my dad was attracted to the materialistic parts of the American dream, and Los Angeles in the eighties had plenty of that on offer, what he really appreciated were the reliable and what he saw as fair systems that were in place. For example, your credit score. “Noreen, in America nobody cares what your name is or how nice you are. The only thing that matters is your credit score. If you ruin your credit, the system will chew you up and spit you out,” he admonished when I got my first card. My dad didn’t find this scheme predatory, callous or threatening but instead reassuring. He felt there was a transparent system and if you played by the rules, anyone could eke out a peaceful, happy life. He didn’t need to be rich, he just wanted to be comfortable. When you consider the haphazard chaos, injustice and corruption that defines Egyptian society till this day you can understand his appreciation for order. A points system that determines your trustworthiness — American commodification at its finest. He just loved it.

There was also an order by which my dad sought to “level up” in LA. From apartment to a house. The city to the valley. A Toyota to a Mercedes. And it was all happening because he played by the rules. A year after I was born, my parents moved from their rental apartment in Hollywood to a single-story house in Northridge. The dream of home ownership in idyllic suburbia was in fact within reach for them as a dual-income family. They bought the house for a tenth of what it is valued at now. It was a different time. He must’ve felt that he had it all.

My memories there come in incoherent flashes. The neighbor’s tire swing. Me, wobbling on training wheels. Dripping creamsicles, shared with neighborhood kids on the sidewalk, “Eye of the Tiger” and “Thriller” on MTV. A magician at my 4th birthday party with an actual bunny. A suburban paradise where kids ran through sprinklers on manicured lawns when it got hot.

But the center did not hold. Shortly before my parents’ divorce when I was 4, my dad booked an appointment at Sear’s Portrait Studio for us to take a family picture. My mom refused, saying she didn’t like being photographed. They fought and my dad took me anyway. This photo — of me in velvet and ruffles, my dad in a suit, and a mottled blue background where my mother should be — is a frame-able testament to my dad’s ability to gloss over reality. Right when he thought his American dream had been fulfilled, his family fell apart, and he didn’t know how to fix it.

My mom was going through her own self-realization journey. Forced to work full-time just months after having me, she also started rising up the ranks in her career. And like my dad, she found a great job in her field working for the Beverly Hilton Hotel, an icon of glamor at the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica, where the Golden Globes are hosted every year. Exposed to a new world, she started to dream her own dream. And supported by her colleagues and new friends, she gained the courage and self-esteem to recognize that my dad’s learned misogyny and temper were not things she had to tolerate. And so, she divorced him. The American ideals my dad had spent the first part of his life admiring — independence, self-reliance, and freedom — actually ended up destroying his family. He felt that my mom had changed too quickly. But it was he who forgot to bury this certain part of his “Egyptianness,” as he had done with so much else of his culture. He was heartbroken and resentful. I was fortunate though that for all his shortcomings as a husband, I only knew him as an attentive, playful, and cheerful father who absolutely adored me. He was a great dad. And I have to thank my mom’s grace for that, too.

When I think of my dad, I think about how the ordinary can take on magical meaning. The way he made normal life come alive for me when LA was our playground. I smile remembering how he’d pretend to trigger the streetlight changing to green by shooting it with his index finger (with one eye on the crosswalk signal, of course). My dad always found a shortcut into the soul of LA by just talking to everyone. He always chatted up the cashier at the gas station or the supermarket. He’d ask waiters when they were getting off and what their plans were. On the way out of a movie, he’d ask complete strangers what they thought. And everybody loved my dad in the Hollywood courtyard apartment complex where he rented for over a decade. There was always someone to greet us when we carried the hamper to the shared laundry room, stopped to check the mail or pulled into the carport behind the building. He’d honk his horn and wave to anyone in the garage from his new pride — a black, Mercedes convertible. “Ross the boss, you’re the man!” they would wave back. He still loved listening to Chuck Berry with the top down.

Although he loved talking politics and was a vocal critic of the government’s foreign policy, my dad was so grateful for his American life. And that translated into real loyalty. After the 9/11 terror attacks, he even applied to the FBI when they made a public call for Arabic translators. We laughed uproariously when after his second interview he was rejected because of his subpar Arabic proficiency. So he just kept showing up for his other dream job with the DWP until he jumped at the chance for early retirement. More time to cruise in his convertible. I remember looking at him once waiting at the car wash, amazed at how much peace he had. With the sun on his face, he closed his eyes and smiled, as if he was meditating on how lucky he was to be there.

In his final year of life, bed bound and declining in the San Fernando Valley, the pandemic endlessly separating us, he told me that in most of his dreams he was driving. I can still hear his booming and jolly voice command, “Come on, let’s go for a ride,” as we did so many times in my childhood. To the beach and back. Up one canyon, just to come down another. When the drive itself was the destination. I wondered if he dreamed about the magnolia trees in Hancock Park that solemnly watched over us for years, like the elders they are. Or was he winding through the palm-lined streets of Beverly Hills, where the trees looked like they were wearing hula skirts? Maybe he was sailing down the California Incline, driving headfirst into the marine layer, taking big gulps of the ocean mist. I had a dream recently of us singing with abandon to KOST 103 ballads on the freeway, our voices evaporating into the wind.

In that period, he also started watching old, black and white Egyptian films. Something he had never done before. I laughed, asking him if he could even understand the Arabic anymore. He said he appreciated the simple plot lines. “So and so wants to marry so and so, blah blah blah” and that he loved the music. He also just liked to think about the “good old days.” With a lot of time to think, I imagine it was his way of reconnecting to his former self, his former home and closing the circle of his life. “A good life,” by his own assessment. Maybe it was also his soul’s way of reaching out to the collective he had left behind in pursuit of well, himself so many years before. If he ever had any regrets about how that pursuit served him in the end, he never let on. Just the opposite, he insisted that I continued my own, no matter what. (Though he did always wonder how I could live somewhere that got so cold.)

Although often stereotyped, LA can be a hard place to figure out and an even harder place to explain. There are so many moments of fleeting and sublime beauty only an Angeleno can appreciate. Like a power line’s shadow bending at an illogical angle, against a concrete wall, in the purple dusk. Or the camaraderie of sitting in traffic on the 405, all of us in union, facing a sea of brake lights. Each face glowing red, just trying to get home. These things were never explained to me, just shown to me. By my dad and through his eyes. The reliability of June gloom. The unnerving Santa Anas. And how you should always, always take Fountain. I’m so grateful that his romantic view of Los Angeles, is my Los Angeles.

Thank you, Noreen, for a beautiful portrayal of your father and his/your life in LA! It was an absolute joy to read and I was so impressed with the complex and complicated, yet totally relatable, description of your dad’s immigrant experience. As an immigrant myself who came to the US at the age of 7, I empathized with both your dad’s and your perspectives of life in America – the love for this country and the desire to be and be seen as 100% American as well as the sad disappointment when confronted with racism and other shortcomings of American society. This is one of the best essay’s I’ve ever read! Thank you again!