An intimate look at two new Arab novels in translation, from Lebanese and Syrian authors.

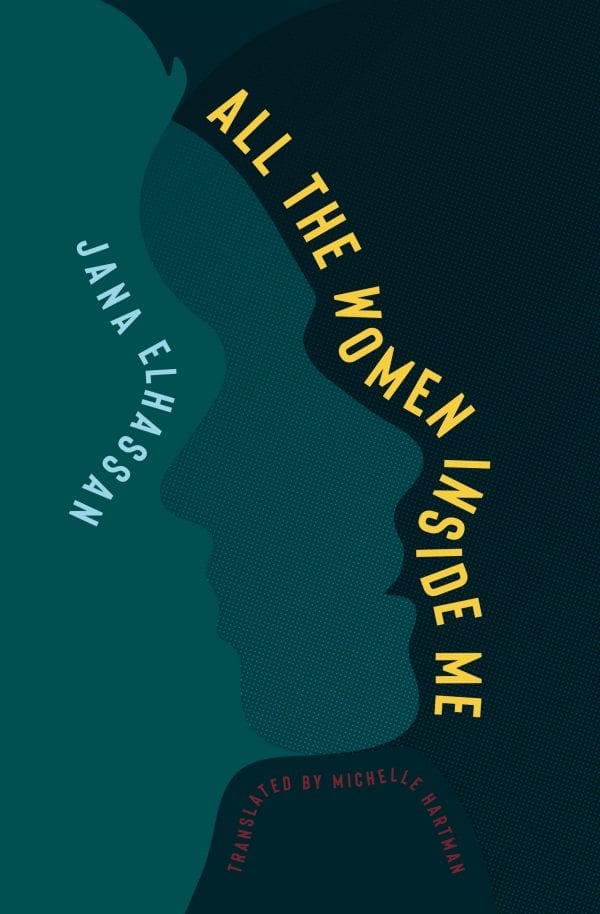

All the Women Inside Me, a novel by Jana Elhassan

Translated by Michelle Hartman

Interlink Books (2021)

ISBN 9781623718862

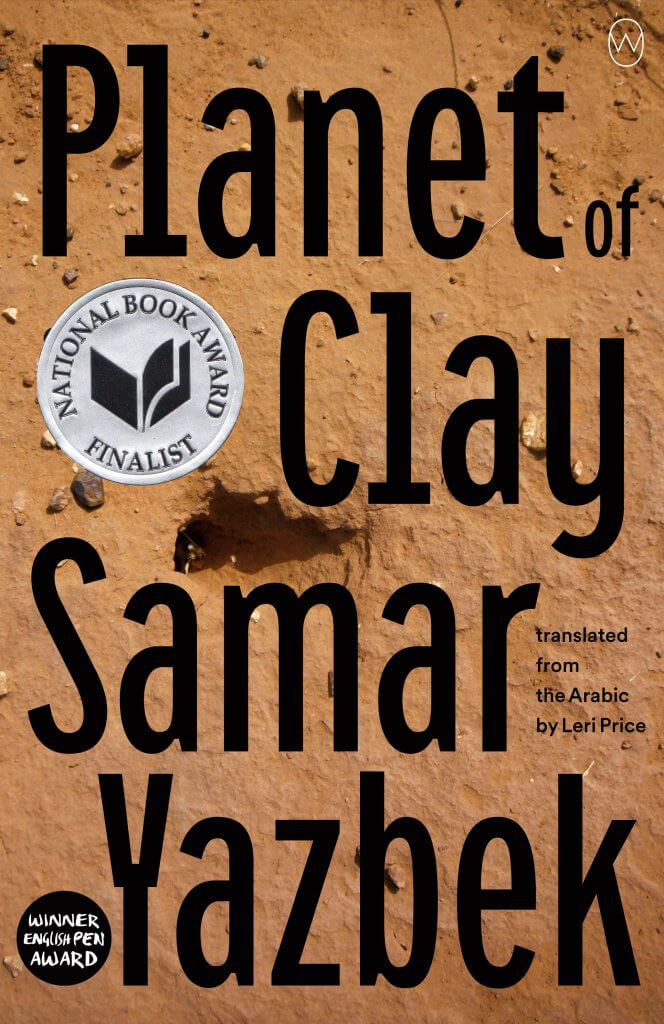

Planet of Clay, a novel by Samar Yazbek

Translated by Leri Price

World Editions (2021)

ISBN 9781642861013

Imagination, as Albert Einstein once said, will take you everywhere, whereas logic can only take you from A to B. Many experts agree that this ability to produce and simulate novel objects, sensations, and ideas in the mind without any immediate input of the senses, creates a place that allows us to make sense of the outside world and to create a new reality within us. This “mental reality” is where most of us escape when at odds with the way things happen to be on the ground.

In Lebanese novelist Jana Elhassan’s novel All The Women Inside Me, her protagonist, Sahar, relies on her imagination to act out all of the desires she has been denied throughout her life as she struggled to survive a cold childhood, overshadowed by her parents’ unhappiness and their distant relationship to her, an abusive marriage, and a series of disastrous relationships. “To be honest,” says Sahar in the novel’s first chapter, “I’ve always loved the things that existed only inside my own mind. I felt safe weaving facts into my imagination, because then I could experience their specificities and be done with them whenever I wanted…I knew that it was Me who was in control.”

Imagination again presents itself as the only coping strategy for the young protagonist in Samar Yazbek’s novel Planet of Clay. Rima is a woman-child traumatized by the horrors and atrocities of Syria’s ravaging civil war. She finds refuge “in a fantasy world full of colored crayons, secret planets, and The Little Prince, as everything and everyone around her is blown to bits.” In a quote published at the beginning of Yazbek’s book she reveals that her choice to remain in the realm of wonder is in fact “to outstrip the violence of the story.”

J.R.R. Tolkien declares in his essay “On Fairy Stories,” that the imagination is a “sub-creative art which plays strange tricks with the real world and all that is in it,” allowing us to morph ordinary elements from the environment, into extraordinary ones. We do this to attain joy, safety, sanctuary, and control, rendering us the uncontested architects of our destinies, free to reclaim the narrative and shape the world according to our desires.

All the Women Inside Me, newly translated to English, is the author’s second novel and was shortlisted for the 2013 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. It explores the reasons why women in abusive relationships keep silent. It also spotlights the social, religious, and political context related to these women’s circumstances, as well as their upbringing.

The novel opens with Sahar, a woman of no agency, recounting a childhood lived in a conservative milieu in Tripoli, in northern Lebanon. Sahar’s father is a lapsed leftist who masks his boredom by busying himself with great causes. Her depressed mother’s nerves are as delicate as the crystal she keeps immaculately polished in her home, and her only hope is for her husband to notice her. Sahar grows up isolated and emotionally stifled, relying on her vivid imagination to conjure up an alternate world of men and women who live vibrant, colorful and fulfilling lives.

In college, she meets Sami, who wants to know everything about her and seems to be the escape she is looking for. Briefly after marrying she realizes that not only is the union an enormous disappointment compared to her fantasies, but that she had “surrendered to her death” under Sami’s domination. Her recourse is to bury her feelings of anger and disappointment alongside her childhood sorrows. Little by little, she is shocked to discover that she has turned into her mother — the woman she had refused to be.

The novel takes a dark turn at this point as Sahar chronicles the abuse and her feelings of humiliation and degradation that come with the beatings as well the annihilation of the self as Sami transforms from the “Absolute” she had fallen for, to someone abhorrent who reduces Sahar to “a body of ashes,” “a black hole, a woman with no scent, a stick broken off a tree branch, lying on the ground for people to tread on as they passed,” while in her imagination she conjures up a magical being with the gift of extraordinary strength.

And while it is evident that the female characters in the novel are a reflection of how patriarchal societies would like their women to act and be — docile, grateful, silent, perfect — the male characters themselves don’t fare much better in such a poisoned environment; a charlatan sheikh trades in religious magic, making a profit off of people’s misery, a boyfriend leaves his great love to marry a “more appropriate” good girl, and a seemingly pious man metes horrendous physical and emotional abuse on a defenceless woman.

Elhassan also explores the dynamic relationship and psychological thread that binds people to place, a process that shapes who we become. As Sami guides Sahar around his childhood haunts in Tripoli and tells her the stories that come with them, Sahar is able to piece together how Sami’s memories of his city, its residents and his family shaped his feelings, behaviors, and identity. In an interview with Arablit, Elhassan explained how she “wrote the city through the body of a woman to show how similar they are and to reflect on how the social context and internal psychological aspects intertwine to produce damaged personas and places.” This conjures American essayist Rebecca Solnit, who wrote how the places in which one’s life are lived “become the tangible landscape of memory, the places that made you, and in some way you too become them. They are what you can possess and in the end what possesses you.”

The novel is a captivating and ambitious undertaking by Elhassan and her translator Michelle Hartman, who according to her note at the end of the book translated the novel in a series of long binge-like sessions during the pandemic, to produce a work that demonstrates how although the life of the mind is capable of offering refuge from psychological and physical abuse, it can also turn into an unhealthy obsession that could blur the line between what is real and what isn’t. Where this novel truly excels is in how it unabashedly poses resonant questions about domestic abuse, religion, motherhood, and female solidarity and insists, despite crushing despair, on life.

Planet of Clay by Samar Yazbek is a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Translated Literature. It is a portal onto the war in Syria as witnessed by Rima, a young girl from Damascus, who is cursed to wander wherever and whenever, as if “wings sprouted between her toes.” Naturally, in a society that places shackles on everyone’s movement, particularly its women “who are forbidden from going around unless it’s for something absolutely necessary and urgent,” Rima’s affliction ensures that her personal space is restricted and controlled from her early beginnings. As a child, she is bound by a rope to her mother’s wrist except for those times when she is tethered to the bed or when she is accompanied by her brother to the mosque. He would tie her to him with a rope long enough to allow him to wait outside the girls’ room in the neighborhood mosque where she eagerly learned to read and recite the Qur’an. “I used to sing the Qur’an,” she says at one point. “Once, I recited the Qur’an to the young man I let touch my chest, he was stunned, and after that a long time passed and I forgot about singing and reciting the Qur’an.”

Although Rima’s “tongue was stopped’ after a harrowing incident at a checkpoint at the early onset of the Syrian war, and she doesn’t understand much of what surrounds her, she soon finds that she prefers to communicate through her drawings, a more apt medium than words. However, after being rescued from a military hospital and tied up in a basement in Ghouta, a besieged suburb of Damascus to which her brother has brought her after rescuing her, Rima, with access to only pen and paper, proceeds to write down her story, primarily about the “disappearance” of her mother, the days “before the summer sky rained those bubbles with the horrible smell,” and the women who sleep in their hijabs who might die at any moment (and they do), worried about their modesty. Young Rima writes and writes, assuring her imaginary readers from the outset that her story is not only real but also the complete truth. She promises more of the same should she survive.

This is a bleak, haunting novel, difficult at times due its heavy subject but nonetheless a powerful narrative from the Syrian war’s most vulnerable. It can be slightly disorienting due to the unreliability of its young narrator, whose voice fluctuates between that of an adolescent and an adult. Yazbek refers to fairy tales and fantasy to hone her themes of women’s freedom, the relationship between writing and violence, and the new language we might construct in the midst of the terrible events we are living through, with multiple references to Alice in Wonderland and The Little Prince, from which the title of the book is derived. “Rima is a woman-child who tells of the war through her initial shock,” says Yazbek in a quotation printed on the first page of the novel.

Leri Price’s translation is exquisite and masterful, a further demonstration of the heights to which language can soar, and a testament to the vividness of imagery, both uplifting and horrific. “I wouldn’t normally recommend translating a book about a girl trapped in a cellar while a global lockdown kept us all trapped in different ways,” Price confesses, “but it must be said that Rima was consistently an enjoyable companion throughout a difficult time … and I hope readers respond as I did to her boundless curiosity, her sharp eye, and her soaring, striving, limitless imagination.”

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)