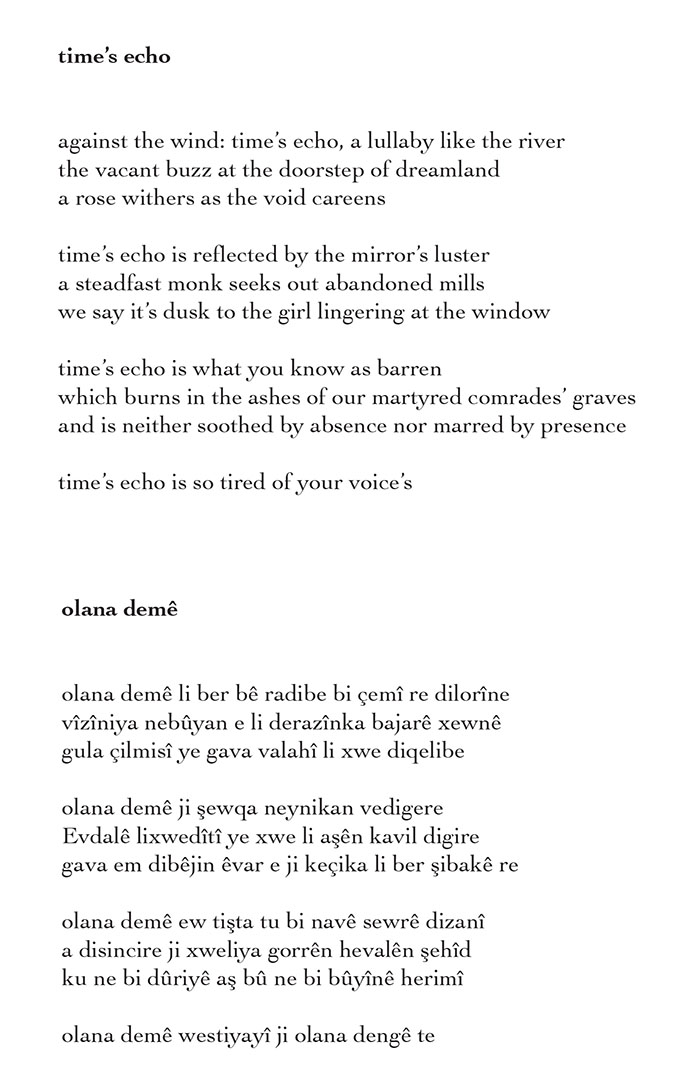

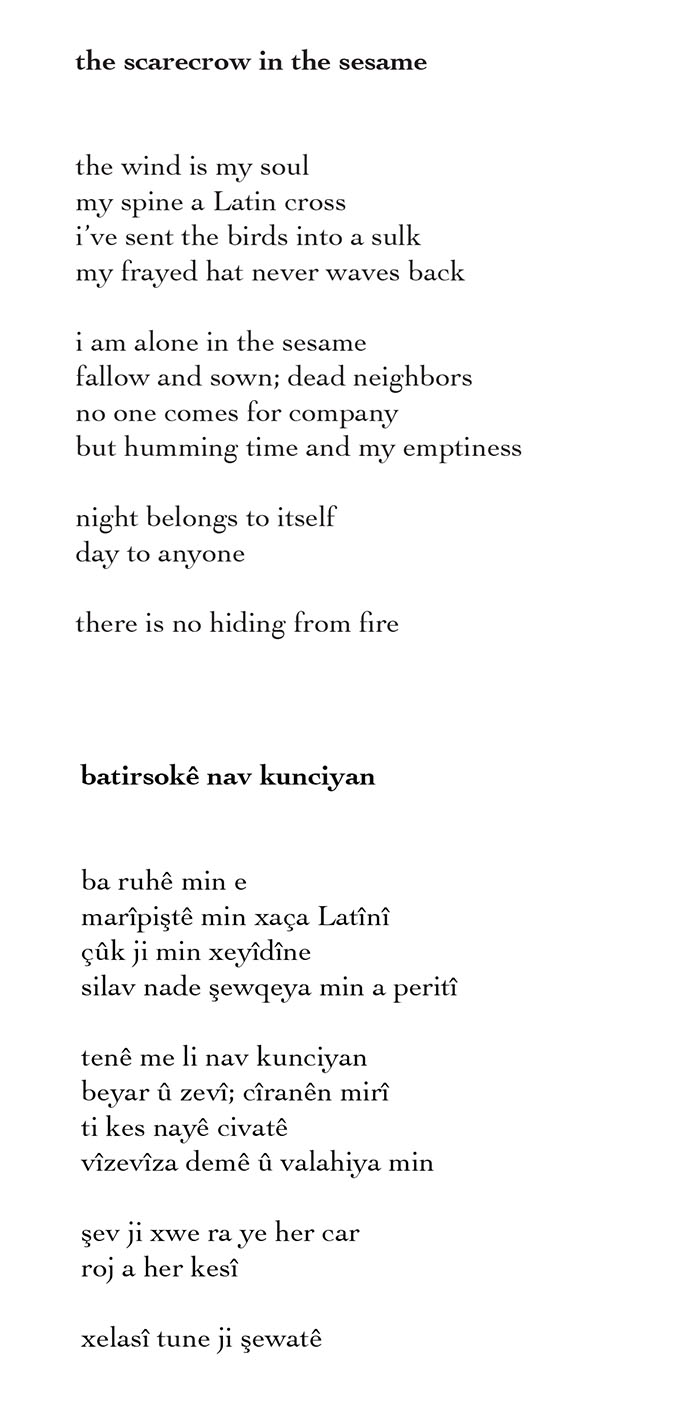

To celebrate the forthcoming publication of Selim Temo's Nightlands, we present here Zêdan Xelef's introductory essay* and two poems from the Pinsapo Press edition, "Time's Echo" and "The Scarecrow in the Sesame."

I was born in Iraq, between a remote village south of Shingal Mountain and a farm to its north, on the Iraqi-Syrian border. I grew up in a Kurmanji-speaking family in a predominantly Kurmanji-speaking region that underwent a massive forced integration, called Arabization, which relegated our language to household whispers. School and state-run television, the only source of information, both used Arabic, Iraq’s only official language under Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime. In disputed territories like Shingal, the more brutally the state imposed Arabic, the more fiercely we continued to whisper in Kurmanji.

In late 2014, after surviving the Islamic State’s genocidal campaign against the Ezidi people, I became aware of my mother tongue as a language of cultural production. I made my first attempts at literacy in Kurmanji. The ruling authorities wanted Ezidis isolated, cut off from the wider world, so our community, enraged, struggled to connect itself, outside of state channels, to the global conversation. I joined the trans-border community of Kurmanji speakers as my first protest to the state-sanctioned violence I had grown up with and the extremism I had recently survived. I also learned English. In that early literacy, I found I needed to address the Arabization not just of my tongue, but of my mind as well, turning back to my community’s oral traditions and searching constantly for any written literature in Kurmanji.

When I came across Temo’s work for the first time, I realized that the way I had started writing in Arabic after forced Arabization in Iraq was how Temo had started writing in Turkish after a century of Kurmanji language and culture being banned in Turkey. In both our nation states, our language was unwelcome, suspect, and, for large spans of time, outlawed. I saw myself clearly in the shift he made from writing in Turkish to Kurmanji, a shift he made after he won a Turkish prize for his debut poetry collection as a Turkish poet. Two decades before I first discovered him —when the general use of Kurmanji was a Turkish offense— he had begun to reconcile identity issues that were critical to me. He was a poet, translator, and scholar who tended to the same oral traditions I was trying to rediscover, not only in his original verse, but in such works as Horasan Kürtleri (Alfa Yayıncılık, 2018), his book on the Kurmanji literature of Iran’s Khorasan region, for which he earned my lasting admiration, and Kürt Şiiri Antolojisi (Agora Kitaplığı 2007), his thorough anthology of Kurdish poetry in Turkish translation.

Temo’s poetry is key to understanding the Kurdish experience in Turkey. His poems invite us into the Kurdish households where folk songs and folktales still flow despite the hardships of speaking Kurdish and the state violence against its speakers. Temo’s poems revisit grief and reinvent it; in his poem “pennyroyal in the city,” a woman pitches her mourning tent within grief, standing before the door of existence. His poetry teems with references to the oral traditions his people celebrate, where grief looms large, and through which they survive and preserve both their memories and language. He speaks to Kurdish poets that are contemporaries (Abdulla Pashew) and historical Kurdish influences (Kurdi, Goran). His poetry reaches inward to his people and his traditions and at the same time outward, to the broader history of violence spanning from Barbarians invading Rome to Nazi generals to the Roboski massacres. In his devastating poem “in Roboski,” he recounts the mothers’ sit-in, the communal vigils they held to grieve their departed children:

in Roboski, they live with their sons’ pictures, my son

they take them everywhere, clutched to their chests

they take them to their gardens, like new-ripe fruit

they sleep on cold, sunken bosoms.

By depicting the quotidian lives of mourners, Temo turns their grief into the torment it is for those who have lost someone. In these poems, grief has a palpable, physical quality that is bound to move his readers:

Temo is one of the leading voices in contemporary Kurdish and specifically Kurmanji poetry. He has published three volumes of poetry in Kurmanji — sê deng / three voices (Agora Kitaplığı 2011), keştiya bayê / air ship (Weşanên Lîs 2016), and punga li bajer / pennyroyal in the city (Weşanên Dara 2021) — and three in Turkish before that. He has also authored Serê Şevê Çîrokek (Weşanên Dara 2006-2010), a series of 12 children’s books. He has received numerous awards including Yaşar Nabi Nayır Poetry Award in 1996, Halkevleri Award in 1998, and the Lights of 2011 in the World from the Hrant Dink Foundation. In 2009, he was appointed Assistant Professor at Mardin Artuklu University, where he attempted to found the Department of Kurdish Language and Literature. When the state refused to grant Kurdish Language and Literature departmental status, he resigned his position. Most recently, Temo was a visiting scholar at Paul Valéry University in Montpellier, France.

* Published here by special arrangement with the author and Pinsapo Press, this text prefaces Selim Temo’s Nightlands.