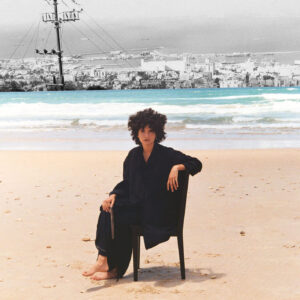

Noushin Afzali

When I was asked to do this month’s artist portrait, my mind wandered through all the artists I know who live in Berlin. As one of the centers of the art world, Berlin brims with creative energy. After much contemplation, I was convinced that Shirin Mohammad is the perfect fit. A young artist whose practice intertwines documentary and fiction, Mohammad’s sharp eyes investigate Iran’s past and present. She then showcases these “unprecedented constellations of historical events” in powerful images.

Shirin Mohammad’s multi-disciplinary practice encompasses archival research, filmmaking, and installation art. Born in 1992 in Tehran, Mohammad earned her BA in Cinema from Sooreh Art University in her hometown in 2015. A year later, she moved to Bremen to pursue her academic studies at the Hochschule für Künste (University of the Arts) in Fine Art. Mohammad now divides her time between Berlin, Bremen, and Tehran.

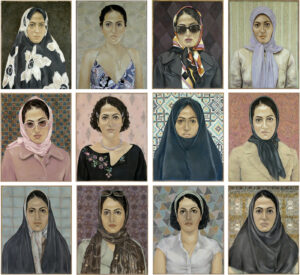

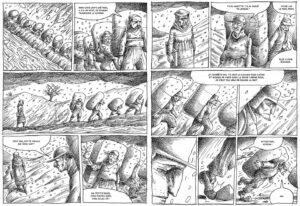

With a particular focus on the socio-political history of Iran, Mohammad creates her own archive by bringing together elements of both documentary and fiction, scrutinizing the remains of lost, ignored, and abandoned narratives. These narratives, either found or fabricated, are in turn an attempt to show how history can be manipulated in different ways. Having received her Diploma in Fine Art from the Hochschule für Künste in 2020, Mohammad spent one year doing her Meisterschule (equivalent to a Master’s degree) with Professor Natascha Sadr Haghighian — in Germany students who have completed the regular course of study with above-average results can start a master class at German art or music colleges.

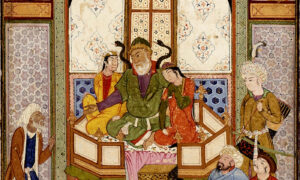

In 2018, Mohammad was the recipient of the Magic of Persia Contemporary Art Prize. The award, which recognizes the talent of emerging Iranian artists, provides them with an opportunity to gain international exposure. The prize led to Mohammad’s first solo exhibition outside of Iran: A house then, a museum now [sic]: Chapter one, Wind of 120 days (2019) at Saatchi Gallery in London. An ongoing project of Mohammad’s, A house then, a museum now researches the history of internal exile in Iran[1].

Having moved to Berlin in the second lockdown in 2020, Mohammad has found new opportunities for her artistic expression in the bustling capital. She is currently a participant of Berlin Program for Artists (BPA), an artist-led organization centered around mutual studio-visits between participants and mentors. Her participation in BPA will result in a group exhibition at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in December 2022. Mohammad is planning on exhibiting A house then, a museum now: Chapter two for this occasion. A research on the history of internal exile as a punishment for political prisoners, the exhibition will bring together hybrid diagrams, assemblages of human and non-human, wind waves and sounds, and multi-channel videos. In this regard, Mohammad rejects the term “activism” in describing her practice: “I see myself in between a reporter and an artist,” she says. To approach this topic, she oscillates between documentary and fiction.

What she most enjoys about her time at BPA is the chance to get to know the art scene in Berlin better, especially through studio visits and the exchange between the participants and the mentors. “The residency has helped me in finding more inspiration and has resulted in building a horizontal community,” Mohammad explains.

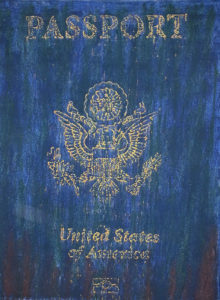

Since many of her projects are location-based, Mohammad has chosen the nomadic lifestyle of moving between a number of cities. Based in Berlin since 2020 — where she has her studio — Mohammad returns to Tehran quite often for artistic collaborations and conducting research. She appreciates Berlin’s active art scene and its abundance of opportunities. However, what she finds problematic is the competitive mentality which manifests itself in various spheres of life. Another hurdle she’s had to overcome is learning to deal with “German bureaucracy.” As an artist, on the one hand, she feels the need to perfect and advance her practice. On the other, the process of familiarizing yourself with the German administration (tax, insurance, etc.) “as an outsider” can be quite taxing and tedious. “You need to find the right strategy of how to situate yourself in this utterly competitive world,” concludes Mohammad.

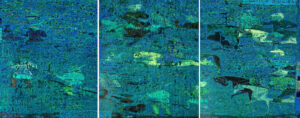

In 2021, Mohammad won the Karin Hollweg Prize for the installation “In the Midst of a Ford.” The installation, which consists of transparent broken glass stickers, milk, fake blood, and LED panel among other things, was about Iranian farmers’ protests against water shortages, power outage, and the high inflation rate in the spring of 2021. The installation accentuated the socio-political relevance of a global environmental crisis and questions of responsibility. The prize has awarded Mohammad with her first solo exhibition in Germany which will open on the 17th of March, 2023, at Künstlerhaus Bremen. The exhibition, a sculptural multimedia installation, is an archival research on certain historical ruptures in the political history of Iran from 1946 to the present and will explore the influence of linguistic expression on political discourse.

“The fatal temporalities of things” is the phrase Mohammad uses in explaining her relationship to Tehran and Berlin. “Shaping your practice in between geographies and in different contexts is like being in a remote bus station. No bus comes and goes and you are unsure where to go. Your practice is shaped as if you are constantly carrying temporalities,” she elaborates.

Her practice has enabled Mohammad to understand the social and political history of her country on a deeper level. One of the challenges of moving to Germany for Mohammad, both personally and artistically, has been how to situate herself in this new environment. “When you displace a person into another geography, it could be very challenging to find your place in your new surroundings and situate yourself,” explains Mohammad. She means this both in terms of human physicality and the body of her work. Playing with this “displacement” has become the core of her practice now. Another challenge Mohammad has been confronted with is how to keep the connection with the reality of life in Tehran. The nature of her practice requires her to be in close contact with what is happening in Iran on a daily basis. Tehran, a metropolis of fast-paced transformations, makes keeping the connection more demanding.

Our stories overlap. I’m also a Tehrani who calls Berlin “home” now. Listening to Shirin talk about her artistic journey through these cities as I’m sitting at my workspace in Berlin and she is some four thousand kilometers away in Tehran (at the time of the interview, Shirin was working on some projects in Tehran), I share her concerns about displacement and the need to constantly situate yourself.

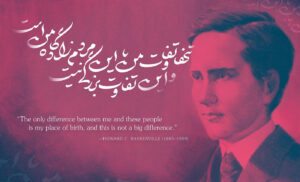

[1] Mohammad Mossadegh — Iran’s first and last democratically-elected prime minister — is perhaps the most famous example of internal exile, as he spent the last many years of his life after his ouster at the hands of Mi6 and the CIA, in 1953, living under house arrest in his Ahmadabad residence, where he was buried upon his death in 1967. Ed.