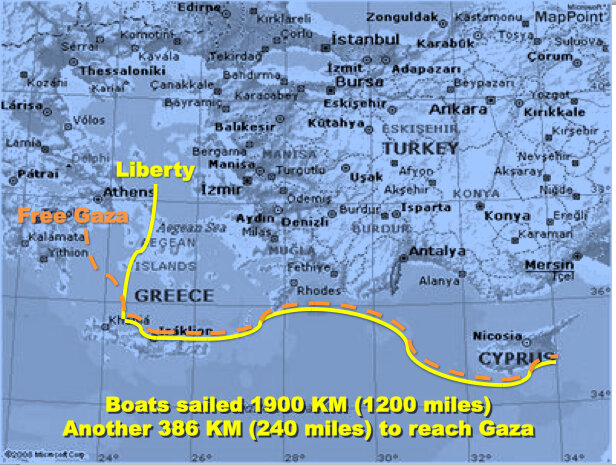

During the summer of 2008, Greta Berlin, Mary Hughes Thompson and other activists from California and around the world sailed for Gaza to break Israel’s siege. What follows is excerpted from the book, Freedom Sailors, an account of how the Free Gaza Movement, which began with a small group of ordinary people, conceived and executed what seemed like a grandiose and audacious plan to break Israel’s illegal military blockade of the Gaza Strip. In a little over two years, they raised the money to purchase two dilapidated fishing boats stored in secret ports in Greece, collected 44 passengers, crew and journalists, aged 22 to 81, and chose Cyprus as their embarkation point. The first voyage achieved exactly what they hoped it would, opening the door just a bit, proving it could be done.

Greta Berlin

They said we would never make it.

The sun was shining in Cyprus when Free Gaza and Liberty finally pulled out to sea at 9:00 am, and 44 passengers, journalists and crew had this overwhelming feeling of joy. We were finally sailing to Gaza. Crowds lined the dock and cheered us on as Free Gaza cast off her lines and headed out of the port, only to find that Liberty had engine trouble again. We had to wait for two hours as the engineer climbed down into the engine room and fixed the fan belt. Finally, the Cypriot Coast Guard escorted us to the 12-mile limit before sounding their horns and turning back. We were on our way, three weeks late, but finally leaving, sailing 240 miles across the Mediterranean to the imprisoned people of Gaza.

The Israeli government had been threatening us for weeks, demanding that we abort the mission, telling us they could not be responsible for our safety (as though we were somehow sailing to Israel and not to Gaza, a territory that Israel had been telling the world was no longer occupied.) We had found Israel’s Achilles’ heel, and we were exploiting it in the media.

Israel had said it no longer occupied Gaza and had not occupied since the government pulled out its illegal settlers in 2005. Therefore, by Israel’s own admission, Gaza was free to invite anyone who wanted to come and visit, to sail into its port and be welcomed. We were not asking for Israel’s permission. We didn’t need to. Gaza was free, and we were coming.

Our two boats could only travel at 7 knots an hour, so we were in for a long and treacherous voyage, 33 hours until we would arrive, the threats from the Israeli government and its supporters of sinking us, then letting us drown, ringing in our ears. The day before we left, my phone rang.

“Do you know how to swim?” said the muffled voice. “What?” “Do you know how to swim?” he repeated. “What?” Shouting into the phone. “DO YOU KNOW HOW TO SWIM?”

Off the top of my head, I said, “I’m sorry. I can’t hear you. You sound as though you’re under water.” At the time, I thought my answer was pretty funny.

Our high-profile passengers like Lauren Booth, sister-in-law of Tony Blair, had been threatened constantly, one caller saying he knew where she lived in France, and she had better go home and watch over her children.

Those of us working with the media had our phone numbers posted on the website as contacts. We often got ‘anonymous phone calls’ in the middle of the night. “There is a bomb on board.” “You will never make it.” “We know how easy it is to sink you.”

We had scuba divers checking the undersides of the boats four times a day, looking for sabotage. Even the Cypriot Coast Guard went under the boats while they were docked in Larnaca. They didn’t trust the Israelis either after the bomb attack in Limassol in 1988, and many in the port authority had talked to us privately, telling us that Israeli agents had been down to the port asking questions.

This afternoon, they had given us a thumbs-up and said we were ready to sail.

We knew the Israeli government was watching us. We knew they wanted to stop us. We also knew the story of the Ship of Return, due to set sail in February 1988 from Cyprus. It was carrying Palestinians and supporters who were sailing back to Haifa to return to their homeland. Israeli frogmen blew up the engine with a mine stuck under the vessel. It was attached to a time fuse, according to port officials in Limassol.1

The blast came less than 24 hours after a car bomb on the waterfront killed three senior Palestinian organizers who were involved in plans for the voyage. There was only one possibility who killed them, and that was Israel. So we took their warnings seriously.

No boat full of internationals had docked in the port of Gaza for 41 years, as Israel tightened the screws of their 20 year illegal blockade ever tighter since 2000, a blockade they said was all about security, and we knew was about stealing the natural gas of Gaza. They just didn’t realize their threats made passengers more determined than ever to sail. We had come on this journey from 17 countries, from Palestine to Pakistan, from the U.S. to Europe. Most of us were activists and had worked in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, some for decades. Threatening us was completely counter-productive.

So far, everything was working, as the boats sneezed and snorted their way across the waves, their diesel engines complaining. The two captains, John Klusmire from the U.S. and the Greek captain, Giorgios Klontsas, were talking to each other on Channel 16, used for transmissions for by ships of the world. Their readings said we might be in for some rough weather but no rain, just choppy constant waves.

We watched Larnaca twinkle into the distance as a cheer went up from both boats, “We are coming.” The journalists from Al Jazeera and Ramattan got on their satellite phones and called ahead to Gaza, “We Are Coming.” It was to be the last set of phone calls made.

Within two hours, beam seas started rolling the two boats around like pieces of debris. Those of us on Free Gaza were doubly pitched from side to side, because the boat had a useless mast that tipped dangerously close to the water as Captain John tried to wrestle it upright. Almost all of us were sick, and the misery was made worse by the spray coming up and over the boat, drenching us and making the deck a slippery mess. We held onto the rails, some even crawled along the outside of the deck, as we tried to navigate to narrow benches set into the sides of the boat and lie down. The Dramamine pills and patches were of little use, as our own fear of what might happen added to our sickness.

After ten hours at sea, the sun began to set, a filmy disk slipping into the water’s edge. We had long lost sight of land and saw no boats. Sharyn Lock, a major organizer from Australia, announced that we were 70 miles away from Cyprus, and we all groaned. It was going to be a long night.

Thirty minutes after the pitch black descended on the two boats, our radio, mobile and satellite phones went dead. The Israeli navy had blocked all communications. We had made plans to keep one satellite phone off at all times, so they couldn’t pick up the number, and we didn’t dare turn that one on until there was an absolute emergency. Captain John said the Israeli communications system would pick up the number almost at once. The only means of communicating with each other over was the low-tech equipment we had brought on board; walkie-talkies. Jeff Halper, chairman of the Israeli Committee Against Home Demolitions was on board our boat and told us we wouldn’t see or hear the Israelis coming if they decided to attack.

One of the journalists was clutching his camera to his chest and lying on the deck of the boat, determined that, if anyone attacked us, he was going to get footage. My friend, Mary, was propped up in the Zodiac, the little rubber boat used for emergencies. She was throwing up in rubber gloves, tying them neatly at the top, and handing them to me to throw overboard. We had laughed at Kathy Sheetz, the emergency room nurse from California who was on board. She had insisted we buy biodegradable rubber gloves, never thinking they would be used for vomit.

“Here,” Mary whispered, “Throw this one overboard and give me a new one.” The glove bobbed off into the waves. “If the Israelis board, they’ll have to lift me up or shoot me right here in the Zodiac, because I don’t have the strength or will to follow their orders.” I hoped that was not going to happen.

Even though it was August, it was cold on the water, and we had not prepared ourselves for the damp. The water had drenched everything and everyone. We had two options; stay above on the deck and be cold and wet, or go down below to the six cabins and inhale the diesel fuel. The cabins were dry, but the diesel fuel made even the experienced sailors gag. Most passengers chose to stay above.

At 22:00, a fire started in the engine room of the Free Gaza, and Derek was down in the hold covered in ash and soot, trying, with two volunteers, to put out the fire and keep the engine running.

I closed my eyes and thought of the two years it had taken us to buy and board these boats and head out to Gaza. People thought we were insane, and, at the moment, I was beginning to believe they were right. The entire journey had been organized through the Internet, and every passenger coming with us had been recommended by at least two other people. Our original passenger list of 88 had dwindled down to 44 as the voyage was postponed, then postponed again, then postponed again. Everything from the suicide of one of the organizers to running out of money had delayed the trip.

Many of us were veterans, working in the occupied territories, but some, like Mushier Al Farra, an engineer from the U.K., just wanted to go home to see his family. The Israeli government had refused to allow him to attend his mother’s funeral, and he wanted to say his ‘good-byes’ to her. Coming with us was his opportunity to enter Gaza without the humiliating searches from Israeli soldiers that all Palestinians trying to enter or leave Gaza endured.

Since 2006, when we decided we would sail to Gaza, the five of us who had organized this voyage had split our responsibilities; Paul Larudee was in charge of the boats, I was in charge of the passengers, Mary Hughes-Thompson was in charge of finances, and Renee Bowyer and Sharyn Lock were in charge of logistics. We had managed to grow from five dedicated people to over two hundred in two years, working together via Internet with the overriding goal of sailing to Gaza.

I crawled into the other end of the Zodiac to try to get some sleep and decided to calm my own queasy stomach by making lists in my head. I ran over the checklists one more time.

Were all 44 passengers checked in and on board? Yes. The oldest was Sister Ann Montgomery, an 81-year-old nun from the U.S. who had worked in Palestine for the Christian Peacemaker Teams and had also worked in Iraq. The youngest, Adam Qvist, was a 22-year-old Danish activist from the International Solidarity Movement whom I had met in 2007 as he was walking Palestinian children to school in Hebron under the malevolent gaze of the illegal settlers.

Had everyone made out a will? Yes. We had no idea what was going to happen, and Ramzi Kysia, head of our land team in Cyprus, had insisted everyone write a will, then send or give one copy to family or friends and leave a copy with him. Some of the passengers thought we were being overly dramatic. It turned out, two years later when the Israelis murdered nine people on our Freedom Flotilla, that it was a good idea to have a will. We also had to leave a contact number, our passport numbers and country of issue and our wishes for getting rid of our bodies.

Almost everyone agreed to be buried at sea, although some wanted to be refrigerated and sent to Gaza, a lofty goal considering the refrigerator on board could only hold soft drinks.

Had we all signed a waiver absolving the Free Gaza movement of any liability? Yes. We would not have taken them otherwise. We had no money and no liability insurance. Every cent that we had raised went into the boats, more than $400,000 by the time we finally boarded them. These donations had come from all over the world, from people as outraged as we were that 1.5 million Palestinians were boarded up in an outdoor prison.

Did we all have life jackets and had we been at the safety session run by our irrepressible Irish first mate, Derek Graham? As far as I could tell in the pitch darkness, everyone on board the Free Gaza had on a life jacket.

I looked around the boat, seeing small orange humps on the deck and people leaning over the rails retching, attached to the ‘throw-up lines.’ We could see across to the Liberty, where three of their passengers, wearing orange, were also attached. Derek had reminded us that, under no circumstances were we to throw up without being connected to the line.

“I’m not coming to fetch ye,” he yelled in an Irish accent. “If you’re fucking stupid enough to throw up over the side and go over, you can fend fer yerself.”

Later, he told us that would never have happened, but he knew we were unaware of how dangerous the waves really were, and if he had to scare the crap out of us, that was fine. Except for the ten members of the crew, five on each boat, none of us had any sailing experience, except on a lake.

I drifted off to a fitful sleep, counting rubber gloves, only to be shaken awake an hour later.

“We need volunteers in two-hour shifts. People who aren’t sick, four to a shift, front and back.” Derek demanded, and several of us on board volunteered to stand watch in two-hour shifts, not to look for Israeli gunboats, but to make sure our boats didn’t collide with each other. The only way the crews on board could talk was via walkie-talkie, and they had to be pretty close, almost impossible in the tossing sea.

Seventy-nine year old, David Schermerhorn, a film producer from the state of Washington with years of experience on boats, volunteered for the 1:00-3:00 am shift, along with me, Sharyn, and Vittorio Arrigoni, a veteran of the sea and a long-time activist and journalist from Italy. I went back to sleep for two hours, rocking in the Zodiac that was attached to the deck. At 1:00 am, David woke me up.

“Time for us to stand watch. It’s pretty quiet right now, most are asleep, but you’ll have to be careful at the stern of the boat. One person back there is pretty sick.” I wandered back to the stern and looked out to see if there was anything that could be seen. The stars were out, but, other than the light on the stern of Liberty, there was nothing on the sea. How did the captains even know what was out there? We didn’t have a single electronic device to even tell us if a ship was approaching.

Suddenly, at 1:30 am, Captain John and Derek both got violently ill, incapable of piloting Free Gaza. John and Derek were experienced sailors; John had piloted all of his life on big research ships. Derek had spent a good deal of his time on the sea. Had someone poisoned them? Was someone on board working for the Israelis? That had always been one of our fears; that no matter how much screening of passengers, one could be bought off or blackmailed into doing the bidding of Israel. Was I getting completely paranoid? I held on to the stern, looking at the back lights of Liberty and wondered if Giorgios was sick.

John handed over the boat to David and Vik. And the two boats did their best to stay together, Giorgios, who apparently was fine, stayed on the walkie-talkie. I stood watch along with Sharyn.

As long as we could see the lights of the Liberty, we felt a bit safer. In a couple of hours, John and Derek were fine. We never knew why they got so sick.

During the dark, cold, wet, miserable and frightening night, huddled together, those of us awake tried to stay upbeat. The three toilets down below deck had stopped working. Derek had yelled at us not to put toilet paper down them, but no one remembered.

The fan belt on the engine on the Liberty continued to split, and we could hear the boat coughing as it chugged along. They were, after all, old fishing boats equipped to carry 11 passengers each, and we had 24 on one boat, 20 on the other. The analogy of ‘boat people’ kept running through my head. We didn’t want to face the possibility we might have two boats with no engines, one with no captain. The worst possible scenario would be drifting at sea, unable to even send out a distress call, and having the Israeli navy finally rescue us, laughing at our stupidity.

As one of the organizers of this ship of fools, I began to despair. What had we done? Had we put 44 peoples’ lives in danger for some stupid idea of sailing to Gaza? Was our two years of organizing, the death of one of our primary supporters and the massive debt we had incurred trying to get the boats ready… was all of that going to go into the drink?

A little after 3:00 am, David woke up Ayash Darraji, the Al Jazeera journalist.

“Does your sat phone work?” David asked. “I know we said we wouldn’t take the risk, but we have a really ill passenger on board, our equipment is dead and someone needs to know where we are. Maybe they haven’t jammed the frequency on yours yet.”

Ayash turned on his phone, actually got a tone and called his office. Although we couldn’t have known it out there in the dark, Al Jazeera released the story of our lost boats, the Greeks demanded to know where their MP was, and Israel, backing off, stopped the jamming of our electronics. But it took two hours until the two satellite phones were working and daylight before the navigating equipment was back online.

My shift was more than over, and I was exhausted. It was 4:00 am. That night was one of the longest nights in all our lives. As the dark slowly faded, we could see boat lights in the distance behind us and wondered if they were Israeli gunboats.

I curled up next to Mary in the Zodiac and thought about how it had all started.

Extraordinario, digno, humano el relato.

A beautiful story of a remarkable voyage!! Free, free Palestine! End the Israeli Genocide of Gaza and US complicity in giving bombs and weapons to kill Palestinians!!