From April 15 to May 30, 2025 at the Ayyam Gallery in Dubai, artist Sama Alshaibi constructs a speculative space for understanding historical Arab cities as microcosms of broader global crises, where past and present collide, and modernization, conflict, exile, and revival intertwine.

Yasmine Al Awa and Sama Alshaibi

What’s it like to return home after 40 years? Born in Basra, Sama Alshaibi is an Iraqi-Palestinian artist who has been living and teaching in the States for decades. Her new solo exhibition at the Ayyam Gallery in Dubai is ‘طرس’ (Tterss). The exhibition brings together mixed-media collages and video art that reimagine Baghdad’s transformation — its peaks, declines, and latent possibilities. Here, Baghdad becomes a site of physical presence and alternative visions, one that Sama Alshaibi describes as “always mediated, annotated, and glimpsed through shifting thresholds.”

Sama Alshaibi’s project focuses on the spatial, material, and technological fragments that narrate the story of a place and its people. After a 40-year separation, Alshaibi returns to her homeland on multiple trips between 2021 and 2023. Longing to reorient herself with a city she had once known more through imagination than lived experience, she does so through various layers of mediums and imagery to reconstruct an abstracted and interrupted history and reality.

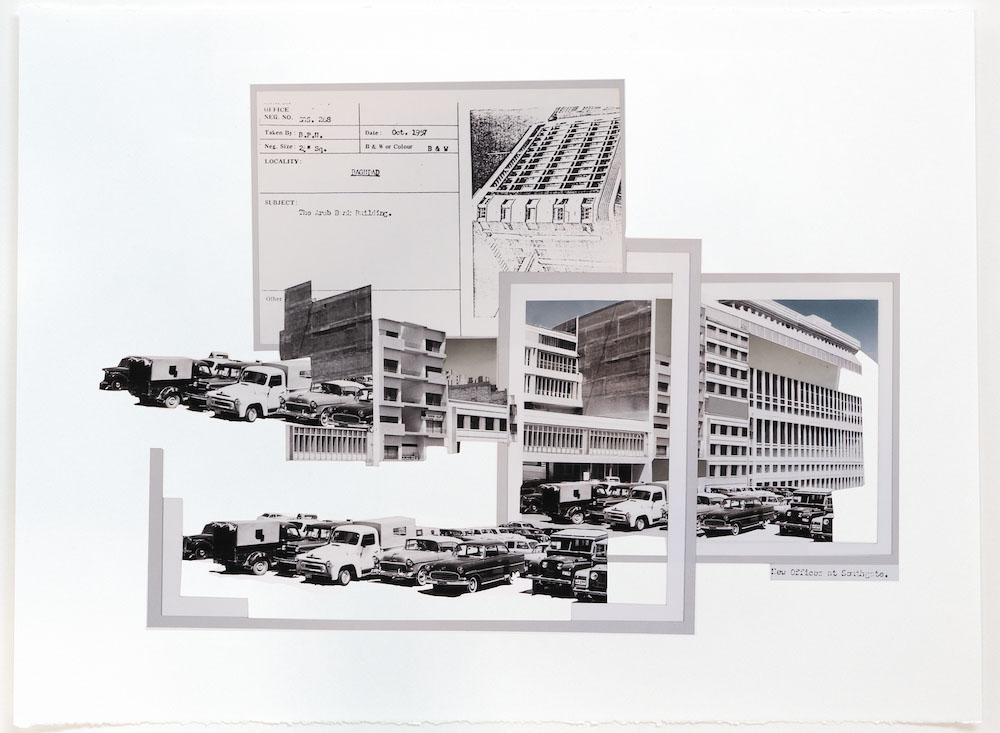

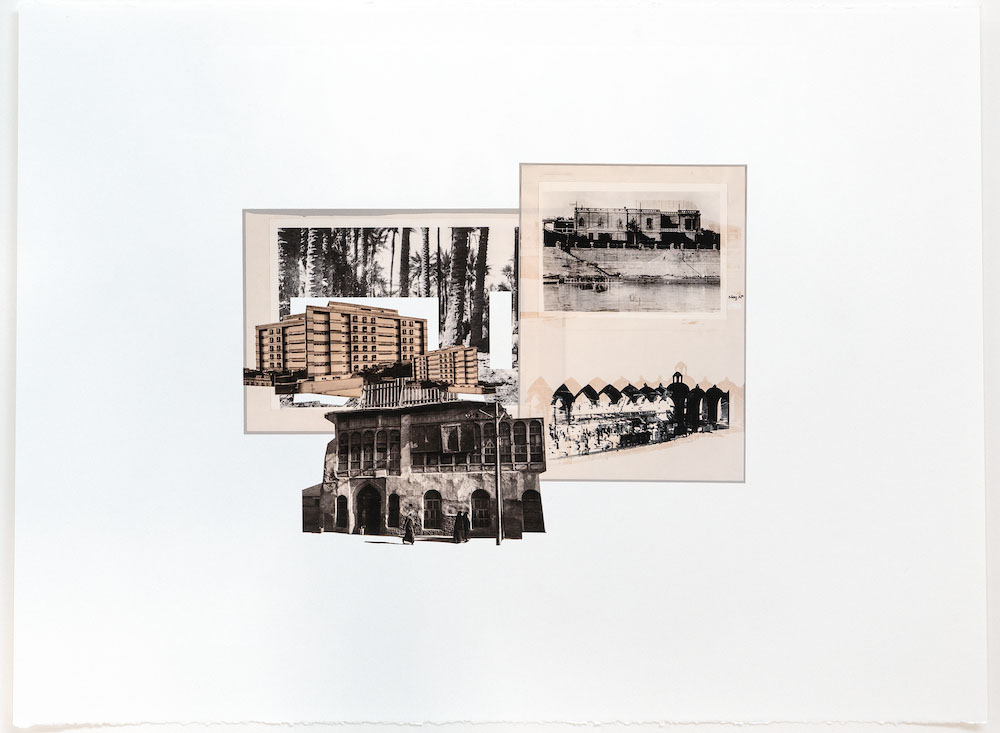

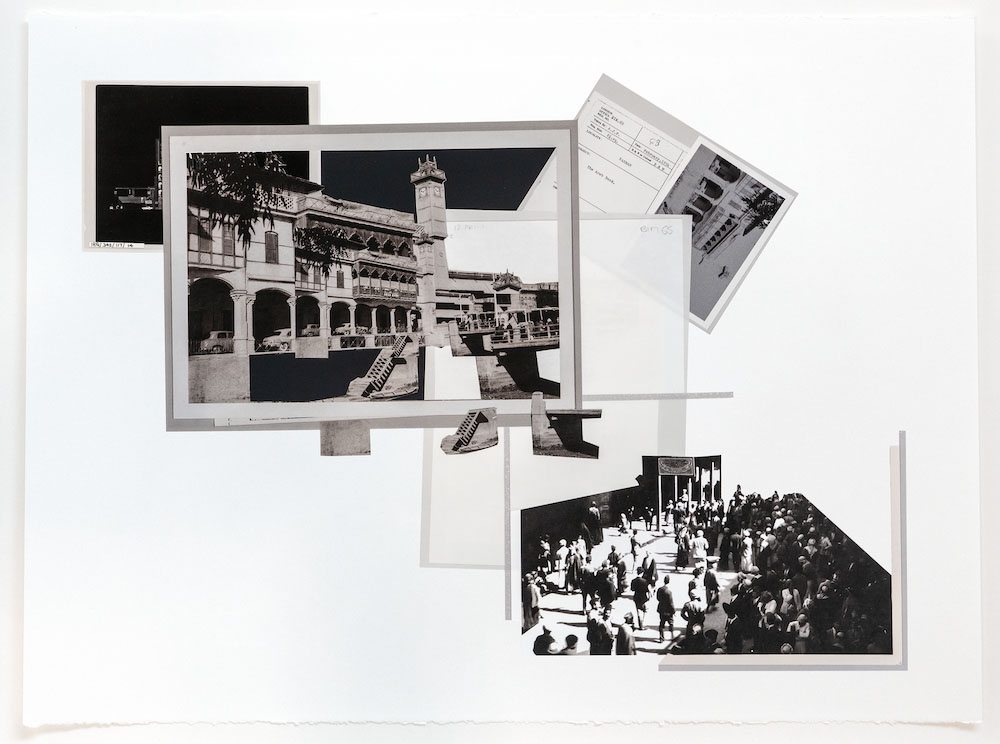

Working with the archives of several architects, including the renowned Iraqi Rifat Chadirji, ‘طرس’, also draws inspiration from Andreas Huyssen’s writings on “miniatures” of urban reality, using them to frame Baghdad through Alshaibi’s lens.

The Arabic title ‘طرس’ evokes the idea of a palimpsest, a concept Alshaibi explores through collages — a medium that mirrors Baghdad’s complex and fragmented urban narrative — layering political, historical, and perceptual imprints to capture its contradictions and progression. The superimposed strata of imagery within the collages immerse the city’s ruins and infrastructures into a deeper narrative of alienation. Alshaibi interweaves the weight of engraved historical memory with the city’s ongoing modernization, emphasizing the tensions and complexities that persist in the aftermath of war.

Using LiDAR technology to scan the urban landscape, Alshaibi built an extensive repertoire of factual measurements, mapping the city’s neighborhoods. Her laser-precise data mappings are interwoven with her photographs and archival materials — including vernacular imagery and architectural renderings — to craft compositions that explore the elasticity between imagining and depicting. The bricolage layers temporalities, technologies, and fragmentations, tracing the evolution of a city shaped by imperial interventions, shifting ambitions, and impossible desires.

Through this complex portrayal, Alshaibi constructs a speculative space for understanding historical Arab cities as microcosms of broader global crises, where past and present collide, and modernization, conflict, exile, and revival intertwine.

Sama Alshaibi on her return to Iraq

Returning to Baghdad after 40 years wasn’t about finding what was lost — it was about meeting what had formed in its place. The city is a layered site of historical sediment, compressed by time, conflict, and survival. It holds traces of what was, alongside new forms that refuse to be erased. There’s a strange kind of resilience in that. Baghdad doesn’t just persist — it speculates, adapts, and rebuilds from what remains.

I was never looking to recreate a sense of home. I knew that any project I’d make would need to reflect the condition of exile — even for the one who returns. That dissonance between memory and material, between presence and loss, became central. But rather than just mourning what’s absent, I try to leave space for what’s still forming. I am thinking about the identities that emerge from the cracks, from what’s been ejected, forgotten, or deliberately excluded from the frame.

This connects deeply to how I think about Palestine (my maternal homeland), and what it means to experience overlapping forms of dispossession. Watching artists be misrepresented or silenced — especially those standing with Gaza — reminds me of the post-9/11 climate, the pressure to flatten or disown parts of yourself just to be heard. But that pressure also sharpens intention. It makes me work with greater urgency, drawing connections between propaganda, water politics, revolutionary longing, and the visual residue of conflict. Each project becomes a movement between mediums, histories, and imagined futures.

One of the most surreal experiences was inside the Iraq National Archive. There’s this tension in the air — an unspoken understanding that these documents hold more than just history. Archives, especially state archives, are never neutral. They reveal what they want to, and they conceal just as much. And sometimes, they become instruments of power, reinforcing a version of events that’s been carefully curated, sanitized, or weaponized.

The archivist never left me alone. He hovered, watching each page I turned like I might smuggle the past out in plain sight. He also wouldn’t let me photocopy anything. So I used my phone instead — snapping images quietly, knowing that OCR could convert them later. It felt both absurd and completely fitting: the gatekeeping of a nation’s memory reduced to a failed attempt at control.

It made the experience of working with the Rifat Chadirji archive at the Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT all the more poignant. There, the trust was palpable — an openness, even an invitation, to let his legacy be reinterpreted and reimagined. There was a generosity in that gesture, one rooted not just in access but in belief: belief in what creative practice can do with an archive. And yet, both of these moments — tense and open, guarded and generous — found their way into my collages. They coexist. One resists interpretation; the other encourages it. But both reveal the stakes of memory, and how fragile the line can be between preservation and control.

One of the things that struck me about Baghdad most was how light — and its absence — felt so familiar. In Baghdad, blackouts aren’t just relics of the past; they’re part of the everyday rhythm. I remembered how, as a child during the Iraq-Iran War, the lights would cut out just before the air raid sirens came. We’d grab what we could and run to the basement bathroom, waiting in the dark, listening, bracing for whatever might follow.

Now, decades later, the blackouts still happen — but the response is different. The power drops out mid-conversation, mid-meal, and no one flinches. A generator kicks in, and the conversation just keeps going. It’s like an accepted ellipsis in the middle of the day. That kind of normalization — of rupture, of absence — says so much about what it means to live through and beyond war. Even working with the LIDAR scanner, which doesn’t rely on light, became symbolic. It kept functioning, indifferent to the blackout. It made me think: what else have we taught ourselves to keep doing, even when everything around us goes dark?