The group exhibition “True Love Leaves No Traces,” in Istanbul, approaches hospitality as an intimate coexistence between bodies and beings. In the exhibition, Hale Tenger and Kostis Velonis, two prominent contemporary artists from Turkey and Greece, engage in an indirect dialogue on the traces of life and death.

Arie Akkermans-Amaya

Hospitality without end

The vegetation at Şelale is so rich and exuberant that it feels almost like a throbbing body, and you would be easily led to believe that it’s a site destined for magic. Known in Arabic as Beit el-Ma, Şelale is the name of a massive waterfall, located on the outskirts of the small town of Harbiye, in Antakya, Turkey originating in several springs that burst out of the mountain, collecting clear water in various basins and ponds that subsequently flow into a valley before entering the Orontes River. It would be a spectacular sight to behold on a summer day; it felt like a temple without walls, a temple destined for love, or for falling in love, or simply for falling. And in fact it was all of that, as we will find out. On the basins, turned into eateries, overflowing with fresh but cold, ankle-deep water, visitors lunch in the company of elegant geese, unable to hear almost anything other than the cascading, tinkling waters. But the waterfall is the site of a myth: Known historically as Daphne, it has been associated with the myth of Daphne and Apollo, since the Seleucid era.

When the god Apollo killed the Python, a great snake that terrorized mankind, he became full of pride, and upon seeing Eros, the god of love, himself a famous bowman, he turned to mock his winged nature. Eros didn’t take this offense lightly and he struck Apollo with one of his arrows, shot right through the heart. With the second arrow he shot beautiful Daphne, a nymph who was a virgin huntress of goddess Artemis. The arrow that hit Apollo was one of intense love and passion, and the moment he was hit, he spotted Daphne in the wild and was unable to contain his passion for her. The arrow that hit Daphne, on the other hand, filled her with repugnance for the god that appeared in front of her. The revenge of Eros was cruel. Apollo tried to approach Daphne, but before he could even blink, she had fled. The god was running and running while Daphne was becoming exhausted and Apollo could almost grab her—he finally did.

At that very moment, Daphne could see the waters of her river-father Peneus and screamed at the top of her lungs: “Help me father! If your streams have divine powers change me, destroy this beauty that pleases too well!” Peneus helped his daughter, and she began metamorphosing into a tree. The topic of the myth is not only love and power, but the possibility of transformation and change. Artistic representations of Daphne’s escape are numerous through the centuries, from the late 3rd century CE mosaic pavement excavated from Harbiye, to the very famous interpretations by Rubens and Bernini (including many others by painters such as Giovani Battista Tiepolo, Francesco Albani or Cornelis de Vos). And yet there’s a contemporary sculpture, “Apollo e Dafne” (2022), by Greek artist Kostis Velonis, which reflects both the nymph’s flight and the condition of her sudden transformation through the perspective of historical change and especially the notion of historical failure.

The sculpture confronts us with this failed couple, of predator and prey—in words of the poet Ovid, who handed down to us the most authoritative version of the myth. It is a reference to failed utopias, but not necessarily drawing our attention toward the state of failure as such, focusing instead on the remains of the utopian project (modernism, constructivism and the avantgarde are Velonis’ primary visual language), and its inscription onto the striated surface of history. Grounded in Tatlin and Rodchenko’s constructivist proposal, and its rejection of style as form, Velonis rejects beauty in a predisposition that he shares with Daphne’s request to Peneus. The destruction of beauty is in the context of 20th century utopias and the artistic movements that accompanied them, a demand for a minimalist realism that will show the inner structure of reality in its truer appearance: All the constituting parts are fragile, endangered, subject to decay, perishable and almost imperceptible to historical memory.

But in fact, beauty is destroyed constantly, and this destruction is one of the fundamental markers of time: It was likely Alexander the Great, the first to discover the springs at Harbiye following the victory against the Persians at Issus, in the 4th century BCE, where it’s told in legends that he drank the sweetest water he ever tasted. But it was his general Seleucus I, who laid the foundations for Daphne, Seleucia and Antioch (present-day Harbiye, Samandaǧ and Antakya). Relying on oracles and divinations, he believed with certainty that he had located the original location of the myth, because of the ubiquitous laurel trees. The healing springwaters at the shrine of Apollo, built on order of the general, in a grove called the Daphnaion, were widely visited as pilgrimage sites in antiquity. The temple was subsequently burnt down completely in the year 362 and Emperor Julian the Apostate blamed the Christians. Although the ruins of the temple survived many earthquakes through the centuries, no traces of it can be found today.

Isn’t this also what happened to Daphne? Didn’t she disappear without leaving traces? Her hair turned into leaves, her arms into branches, and her legs into roots. Before Apollo could fully gaze into her, she had already disappeared. The only thing standing was a beautiful laurel tree. But even after Daphne’s transformation, Apollo did not abandon the pursuit of love: “Since you cannot be my bride, you must be my tree! Laurel, with you my hair will be wreathed, with you my lyre, with you my quiver.” And since then, the laurel tree became a sacred tree for Apollo, and the wreath of laurels his symbol. The wreath of Apollo is an image of his unfulfilled love, but also a symbol of victory, glory and power. These utopian remains are something other than a fossilized moment or an archive; it is a transtemporal symbol that articulates the contradictions of history. And this history is not a continuous narrative but a mere fragment, the material taken out of context, the impossibility of permanence. The throbbing body of an ancient spring today.

Velonis’ sculpture of duality and symbiotism—two bodies attached to each other, is part of the large group exhibition “True Love Leaves no Traces”, on show in Istanbul at Galerist, attempting to grapple with the question of hospitality, but not within the Biblical tradition or in a context of vertical hierarchies between guest and host, but in a more complex setting where there exists an unconditional reception of the other, the uninvited, and the stranger, in such a way that the constituting parts merge into a seamless organism—whether you call it life, the body or politics.

This hospitality does not depend on whether the guest may be welcome or not, but on a relationship in which something not technically alive, becomes a living organism only by association with its host. The curator of the exhibition, Burcu Fikretoǧlu, drew inspiration from a fascinating, autobiographical text by the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, “L’intrus”, where he speaks about a heart transplant that he overwent and the strangeness of this experience.

Saved by an anonymous donor

In receiving an organ from an unknown donor, the boundary of life and death expands, as Nancy explains: “What is this life ‘proper’ that it is a matter of ‘saving’? At the very least, it turns out that in no way resides in ‘my’ body; it is not situated anywhere, not even in this organ whose symbolic renown has long been established?” L’intrus isn’t a stranger whom we can invite into our homes, but an intruder, one that will claim the space on his own, and will make the host someone other than himself: “A life ‘proper’ that resides in no organ but that without them is nothing.” The intruder is not a living being yet, but will become living through the host’s disposition towards life. The traces of the strangeness will eventually disappear but the acknowledgement of risk, of contingency, of unpredictability—an organ might still be rejected, becomes an act of unconditional acceptance. The strangeness becomes an ordinary event, and it is precisely the memory of this foreign body that the exhibition is attempting to highlight.

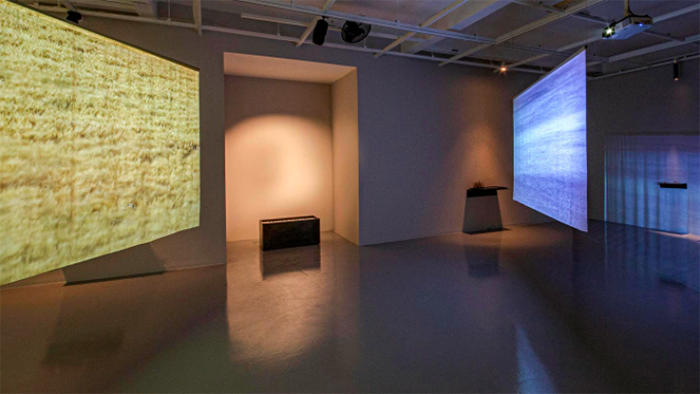

The heart as an organ is here a metaphor for the throbbing of this physical body, undergoing change, assimilating, becoming sentient but also becoming other. “Happens to the Heart” (2022), a microprocessor-controlled sound installation by Turkish artist Hale, invites us to experience the living heart, invading the host and becoming alive in the process. The work is a structure floating up and down, composed of loose orange silk fabrics forming a cube, creating a vacuum effect, as if we were in the presence of this new heart, nestling in the rib cage, and the person is breathing out a sigh of relief at the improbable but amazing continuity of life. The rhythmic sound of the motor pulling up the silk pieces inside of the airy cube takes the place of a life support machine, animating the heart, transforming dead tissue into a living organism. Is this a miracle? In fact we’re dealing with very secular wonders, for as Nancy tells us, the wish for survival and immorality is an element in modernity’s program of mastery over nature.

After taking Nancy’s “L’Intrus” as a point of departure, both Tenger and Fikretoǧlu turned to the songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen for insights on the oneness and sameness of feelings, embodiment and experience. The title of the exhibition derives from the chorus of a 1977 song, which tells us:

True love leaves no traces

If you and I are one

It’s lost in our embraces

Like stars against the sun

Tenger’s inspiration was “Happens to the Heart,” a song written in the summer of 2016, a few months before Cohen’s untimely death, and said to be largely a reflection on the five years that he spent as a Buddhist monk in California. The song was released as the first single of his posthumous final LP, “Thanks for the Dance.” There’s a striking correlation between Nancy and Cohen here, in regard to the possibilities afforded by life and death, the surrendering of the self and the seamless surrendering to and into the other. In the song, the rapprochement between living and nonliving is smooth but unavoidable. The installation is enveloped by a tune extracted from Cohen’s song, recorded by Serdar Ateșer.

Sure it failed my little fire

But it’s bright the dying spark

Go tell the young messiah

What happens to the heart

In her recent work, such as “Where the Winds Rest” (2019), inspired this time by Turkish poet Edip Cansever, Tenger deals with surfaces of history that at first seem ordinary, innocuous and neutral as images, but that soon become latent, and reveal dangers lurking underneath, unexpected threats and risks, unknown layers in a fragmented narrative. Similarly in the current exhibition, the installation stands not only for the diastole and systole of the heart, but also for the way in which modern life unfolds: The narratives of civilization are artificially sustained in a world that is both chaotic and violent, and always in constant motion and change. The invisible cube of the heart, both organ and container, formed by the emptiness around the floating silk, blurs the distinction between inside and outside, in our history, in our personal lives, in the physical borders of politics and reality, and in our bodily existence. This constant loop of ups and downs is nothing like an extraordinary event—it is just bare life itself.

The uncanny element in the installation is not the surprise or unpredictability of the event—a new heart, new beginnings, the renewal of a narrative, but the sense of continuity: The cycles of the living heart, not unlike those of time and nature, continue on account of the hardships of conflict and love, and not in spite of them. It is through the encounter—which can result in other ways than desired, that the human person as a whole, in the singular only a combination of atoms and particles, becomes a plurality of stories and experiences, always shared with others. Hospitality here becomes more than simply hosting, it is also a common production of space which saves passing time from total ruin by means of memory. Artifacts of memory, whether archaeological, technological, or simply historical, however, have no context or life of their own without the entire dynamic system. What is an organ without a body? This speaks also to the alienated individual, unfree insofar as he does not partake in the common world.

Leaving no traces

What does it mean then to leave no traces for Velonis and Tenger? After the destruction of the temple of Apollo, the waters of the spring of Habiye continued to be identified with the myth and practices of divination and dream incubation are still carried out today in neighboring sacred sites by Arab Alawites, the present inhabitants of the region. Coins are left often in the many water basins by those asking for good luck, making vows or wishes. The traces of lived history, though invisible, are symbolically carried by generation after generation of words, supplications, images. As Daphne fled her captor, she fell out of balance, in the same way that the world falls out of proportion and scale, during times of crisis when perspectives are shifting. After stumbling, she changed her world—for her world had changed as well, by becoming something else. This transformation of the nymph from naiad to dryad, from human to nature, is not a mere disappearance, but a transition between culture and nature. It is the violence of civilization.

Nancy tells us about becoming this strange self: “It’s not that they opened me wide in order to change my heart. It is that this gaping open cannot be closed.” Once the body has been altered, a plethora of contradictions arise between inside and outside, self and other, that can no longer be overcome. Who is the intruder after all? He concludes his text thus: “The intrus is none other than me, my self; none other than man himself. No other than the one, the same, always identical to itself and yet that is never done with altering itself. At the same time, sharp and spent, stripped bare and over-equipped, intruding upon the world and upon itself: a disquieting upsurge of the strange, conatus of an infinite excrescence.” In Tenger’s “Happens to the Heart”, the physical configuration of the heart is rational, a model of nature, but in the presence of the unexplained, unaccountable, living breath, the heart remains only a faint trace.

If we’re speaking spatially, for Velonis, utopias of the European 20th century also represent a sense of alienation, but in his case, from the unstable architecture of the present. This alienation is then translated into an inverted nostalgia that sees the future as the restoration of an unrealized or disfigured past. In terms of the laurel wreath, of the god Apollo, what kind of glory wreath is this? Perhaps the “κλἐος” of the Greek epic, with the implied meaning of what others hear about you—the hero’s glorious deeds. But this kleos can come only to those who have become immortalized through their heroism on the battlefield, and who are, therefore, no longer mortal or living. The accumulation of historical cycles of collapse, embodied by Tenger’s translucent time surfaces, by no means linear, tell us that in the absence of gods, there’s no beyond or afterwards. It is the impossibility of permanence, what constitutes the only horizon of transcendence in the world. Is Daphne alive or dead then? As the pumping heart signals, we’re always living and dying, changing, passing, returning, at the same time.

“True Love Leaves no Traces” is on show at Galerist, Istanbul. The exhibition continues through March 26.

Acknowledgements: Burcu Fikretoğlu, Karina El Helou, Jens Kreinath, Hale Tenger, Barıș Yapar. In Memory of Sarkis Buchakjian.