I return to Santiago, Chile in the wake of the global pandemic and “The Estallido” — a social uprising that has changed the nation. A new constitution is written as 35-year-old socialist president, Gabriel Boric, is sworn into office.

Francisco Letelier

On the streets, everyone wears a mask…there are throngs of people in the late summer sun. What’s happened here since I was here last is staggering.

Outside the metro stations vendors assemble wares; they transport goods, conserve perishables, sell them in batches.

Things are practical, utensils unnecessary.

During the social uprising that started in late 2019, Chileans would arrive at the barricades with food and drink for those who held the line against the police, fellow protesters who became legendary for their resistance against the government. Empanadas — a type of baked or fried turnover consisting of pastry and filling — and wine (one of Chile’s most common and appreciated national products) are the primordial nourishment of nomads, workers and protesters. Added to the national menu are lemons and clean water used to soak the bandanas that help protesters breathe, countering the effects of tear gas.

I walk through the recent barricades, marveling at the rebellious graffiti, art and shrines that cover any and everything along the way. Security forces lurk in a line of battered riot vans, parked along the avenue, preparing for the protests and gatherings that continue even as President Boric takes the presidency.

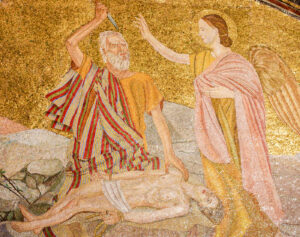

The anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the 13th Century describes recipes for empanadas. They are gathered from a region that extends from Spain and Portugal to North Africa, a crossroads where the west cross-pollinated with the Muslim world. Often these recipes were carried to the Americas by Moors and Jews fleeing the Inquisition of 1492, after 800 years of Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula ended.

Latin America and the Arab world share intimate histories generated by exile and migration. The Arab community in Santiago is felt on the streets and in our food, leaving an indelible mark on the nation. The empanadas of the Americas are close relatives of Arab fatayer or sfijas, and across the river in the Recoleta and Patronato neighborhoods and throughout Santiago, they are widely available.

In Santiago, empanadas are as Chilean as red wine despite a growing number of migrants from Haiti, Colombia and Venezuela, many would be surprised that other nations also have a claim to empanadas. In Chile, a pino empanada is a perfect mix of onion, beef, olives, eggs and raisins — ingredients found in Chile were added to recipes brought across the Atlantic, creating a hybrid relying on a dish the indigenous Mapuche natives called pirru.

But on the Latin American continent many other varieties exist; tucumanas, salteñas, the allaca, arepa or pacucapa, to mention a few. In Argentina it’s a national cult, with many historical varieties and in the Cauca Valley of Colombia there is a monument in their honor.

These are worlds not restricted to lines on maps but molded by pressure; the rise and fall of economic interests and waves of nationalism and political movements, where inequalities and inequities are joined in an inescapable block chain of economic practices.

I have dreamt about this place since the first compelling images of students protests were spread around the world in 2019. With my son and nephews, we walk through what was known as Baquedano Plaza, today called Plaza Dignidad, where only a pedestal remains on a circle ground to dry dirt. The entrance to the metro station has become a monument of memory and a community garden. Below, burned out sections of the station are closed to the masses; destroyed by looters, police provocateurs, or both.

I feel a sense of homecoming to be at the epicenter of a movement that bravely challenged the legacy of the military dictatorship.

But it’s a couple of blocks away when I feel I’ve finally come home. We give our orders to my nephew, Jose Miguel, who calls ahead. As we near our destination, I can smell them baking and see that some people are finding a place to sit along the street or park. It’s Friday and the weekly demonstration has started; we walk towards empanadas and my mantra of Chilean freedom is “una empanada de pino al horno y una empanada de queso frita” (one oven-baked pino empanada and one fried empanada of cheese).

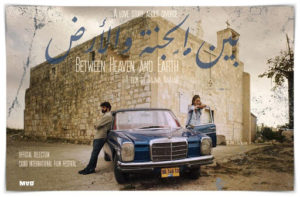

There are many kinds of exile. My family was forced to leave, while others escaped distant lands to arrive here. Santiago is home to one of the largest Palestinian communities in the world, and hosts a notable gathering of Arabs from other countries, including Syria and Lebanon. Consuelo, married to my cousin, describes how her extended Lebanese family exchanges love and memory through food. Uncles argue about how to brew the best coffee, using cardamom and finjan coffee pots. Boiling points, vessels and the addition of cool water to cool and temper the brew become metaphors for the constantly shifting conditions of exile and cultural legacy.

I am crying and it’s not the tear gas wafting towards us from Plaza Dignidad. The sound of sirens and chants blends into the din of the city, as people casually stroll through the park. Street vendors and musicians gesture towards those who sit along outdoor dining patios that have appeared all over the city during the Covid era.

Across the table, my American son, Matias, bites into an empanada. When I bite into mine, it’s more than forty years since I have felt this possibility, a sudden and overwhelming wave that assuages years of loss and exile.

In 1971, before the US government colluded with the Chilean armed forces to overthrow his government, President Salvador Allende promised us that we would build a culture of “empanadas y vino tinto” (red wine). It was his way of saying we would address inequality. Today’s President, Gabriel Boric, was inaugurated last week and he has promised to continue that society we once dreamt of.

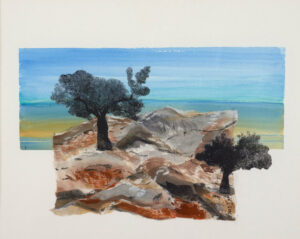

When we come home, we sit up the street on an apartment balcony overlooking the site where the uprising began. Small hawks chase pigeons among the treetops of Araucaria and Oriental Plane trees. Flock of parrots squawk across the park and the Mapocho River. In the distance, the surrounding Andes glow in the approaching night.

A few miles west, street vendors are unhappy with demonstrations by high school students. The National Confederation of Students has called for a mobilization because of government food grants for high schoolers. For ten years, students have received the same amount of 32,000 pesos a month — roughly 1,600 pesos a day or around $2 dollars for nourishment while in school. That amount hardly buys an empananda.

The government closes metro stations on Friday nights when protests are planned in fear that stations may be vandalized or destroyed. Vendors count on the crowds at Central Station, but tonight there is no one to buy their offerings.

When the line of students approaches, vendors barricade the street, armed with long sticks they turn crowds away with violence. On social media, some attackers are seen holding firearms, other wearing the black head coverings often equated with political protesters. Earlier a policeman has shot a protester.

As Santiago returns to life in the streets after two tumultuous years and President Gabriel Boric, 35, installs a feminist cabinet promising reforms and action, new challenges arise that might keep us from quickly realizing the culture of empanadas and red wine that Allende struggled to achieve over the course of many decades.

I have returned to perhaps say goodbye to my mother, who is 91 and in poor health after losing her eyesight and mobility in the long Covid lockdowns that were put in place as the country reeled into the global pandemic. Each drink of wine, each empanada, each pisco, mote con huesillos, maraqueta or pastel de choclo, eases the grief, giving the comfort only food can bring.

My father was 42 when he was killed by the Chilean secret police aided by agents trained by the CIA. It has taken forty-six years for me to taste the empanada promised to me by Salvador Allende and now shared with a living piece of evidence and history, the piece of exiled heart that is my son. Monarch butterflies take many generations to complete their cycles of migration.

That night at the sparse and clean tattoo studio of my niece’s partner, I watch my son and nephew get twin tattoos written on their arms, Presente , Ahora y Siempre (Present, now and forever), a slogan from Chile’s fight against the dictatorship, repeated often when we remember all those we have lost; barricades and loves, empanadas and harvests of grapes, transformed.

The needs of street vendors is acute, many work illegally while new immigrants from Haiti, Venezuela, Columbia and Peru work the streets to survive. The smell of marijuana mixes with that of toast, while smells of food from other places blend with those more familiar.

It seems ironic that students who march for food are beaten by street vendors who may suffer in the short-run but will surely be rewarded in the long run by buyers with more to spend on what is sold.

In some places tonight there will be no exchange. Weary and impatient for change, some believe that it can happen through decree, only a matter of will by those who hold the reins of government. Others who like me have seen things come and go, know that taking things apart is easier than putting them back together and so we will reach for comfort and nourishment as we always have. Creating our own version of a culture based on the free exchange of ideas, empanadas and red wine, we continue to believe in possibility and know that we must work hard to find recipes that work.