This is Part II of Rana Haddad’s Syria Through British Eyes.

What a British person imagined Syria or the Middle East to be, what he or she thought about us Syrians without ever having set foot there, was still more important than what I or people like me thought. We were subjective, but their opinions were objective. That was the message.

Rana Haddad

When I moved to England with my family in 1985, it was a shock to realize that the way we Syrians saw ourselves was not how the world saw us. School children asked me if we rode camels back home. Most people simply had no idea where Syria was or who Syrians were. On the rare occasion that I heard the name Syria mentioned on British television or other media, it was always in the context of some dreadful event.

For example, there was the breaking of diplomatic ties between Syria and the UK in 1986 due to the bombing of El-Al flight 016. My Dutch and Armenian maternal grandparents, who lived in England at the time, tried to persuade me to give up my Syrian passport, to put that identity behind me.

“You are not Syrian, you are Dutch and English,” they insisted.

Am I? I wondered. Was it really possible to delete nearly 16 years of life in Syria, to erase all my memories and impressions of that beautiful land and people, and to replace them with images from television screens in my adopted country?

In A Room of One’s Own (1929) Virginia Woolf asserts: “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.” It took me many years to understand that what men had done to women for centuries, the West had done to the East, and for similar reasons — not in order to reach any objective truth, but to feel better about itself.

The East did not always reflect the West back to itself at twice its size, but sometimes ten times so.

In my thirties I landed a job with the BBC as a freelance journalist. I worked with them for more than 12 years and over that time something extraordinary became gradually more apparent to me. Time and time again, before commissioning a story, the editor would write down its contents-to-be — including the conclusions. Accordingly, my job as researcher or producer was no more than to find footage, or proof for said story, often commissioned by an editor who had never set foot in the Middle East, and whose sole source of information was Google, and only in English. If the story on the ground did not “fit,” the footage was rejected during the editing process. Thus one piece after another was produced, telling and re-telling to the audience the same rigid story they were expecting to hear, but with increasingly gory or tragic details. The details in high demand were always those that would elicit from the audience feelings of concern, desperation and pity, and also an inescapable smugness. When I tried my hardest to fight for more nuance to be added, or for different, less one-dimensional stories to be commissioned, I would hit a wall. And in the end I gave up and abandoned this frustrating profession.

During all those years, I was slowly writing a novel set in Syria that I had begun working on at least eight or so years before the war that erupted in 2011. The book was cheeky, funny and satirical, but it was also about a character’s quest for her destiny. My eponymous character Dunya Noor was not a victim but a heroine. I found a literary agent soon after having written only three chapters. But when she sent my first draft to publishers, I hit the same wall I had encountered in journalism. Publishers were not able to see how a story like that set in a country no one had heard of, in “Syria,” would find a readership. They loved the writing and style but I was told that had the novel been set in India or Pakistan or some other former British colony then it would have been more marketable. There was no Syrian community in the UK at the time, as Syria was not a former British colony. “You should’ve written the novel in French,” I was told.

For all intents and purposes during those decades before the war, Syria did not exist, particularly in the Anglosphere. Or it existed as a footnote. Labels such as “Axis of Evil” were bandied about. I was still struggling with the continued cognitive dissonance of hearing about my country in a way that did not square up with what I knew. I began to wonder whether I had hallucinated my entire childhood. How could what I remembered be true when all I heard about Syria was the opposite?

What I heard or saw or was presented with (in a repetitive loop) did not fit even minutely with my own experience of Syria, nor with the experiences of countless other Syrians who had lived there, even those who had left and returned for holidays. Nor did it square with the few western tourists who had gone off the beaten track and visited this extraordinarily beautiful and exquisite country, so difficult to describe in only a few sentences. That beauty and unique nature were hidden behind a hostile or dismissive barrier based on an intense and ancient misunderstanding which could only be described as hostility, whose origins I never quite understood.

Many years later when I was ready to send another draft of my novel The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor to publishers, the war in Syria had begun. This story, which was set in Syria from the 1970s to the ‘90s, was rejected a second time by publishers because it was considered too funny for a novel set in Syria. I was told that readers would be offended at so much laughter and a story focused on the quest for the meaning of love and one’s destiny

Such a story was not what the public wanted to read, I was told. It was suggested that I rewrite the book with style and content similar to The Kite Runner, turning Dunya Noor from the heroine that she is into a tragic victim of some sort. Instead of provoking laughter, she should elicit tears. This was needed for the book to fit into any storyline the publisher expected of Syria. Anything outside that expectation somehow did not belong in the cannon of Arabic literature in English. Those editors had never spent time in the Levant, let alone in Syria.

Did they believe that Syrians don’t laugh, that they are not sarcastic? Do Syrians not contemplate art and love? Do they not have dreams, quests and destinies besides the ones forced upon them by western journalists and historians?

I was told to forget about my unrealistic Syrian novel and to work on my second novel which was going to be set in London. In London you can tell all sorts of stories … about war, about love, funny stories, tragic stories. But if I were to write a story set in Syria then it must be very much a tragic story and a dark story, or else it would not fit. But when I looked into my own truth, I found it hard to write a tragic story about Syria. I was forced to make a choice: either being true to my own experiences in Syria, reflecting that in writing and consequently being ignored in the West as an author, or following the trend of telling tales of suffering and woe to an audience hungry for such tales, especially when they came from the part of the world where I was born and raised.

Cognitive dissonance reigned supreme. Was I crazy to see Syria in this light, and to remember it differently from how it was presented to me in western media outlets? Even publishers with little to no experience in Syria seemed to know more than I did.

Had I been watching TV in Beirut, Dubai or in Damascus, I might have seen all the usual dark current affairs stories about Syria, but not only that. I would also be watching comedies, and seeing singers, artists, professors, business people, designers and filmmakers from Syria. I’d be going to restaurants, meeting people and listening to their conversations, learning about their lives. My picture of Syria would bear no resemblance to what I saw on British or American, or even German or Dutch TV.

So I decided my book would tell my story of Syria, not the story the publishers wanted to hear. What you’ve been hearing about Syria over the past ten years is a single story, only one story or even half a story repeated over and over again until it became a rigid fact that overshadowed all others. The soundtrack to Syria has become that of bullets and bombs, set against images of flattened cities and an exodus of biblical proportions.

Before that story of bombs and exodus began, what did you hear about Syria? I bet nothing of much depth or significance.

Telling only one story about anything is not simply lazy, it is dangerous. Why? Because by telling that one story, you take part in making yourself ignorant. You dig yourself into a hole where you only see things with a narrow perspective, and you make yourself incapable of acting in the most successful way, because you are dangerously out of touch with reality, and you also justify your actions and your lack of action.

It’s dangerous to tell only one story about Syria, the story of war.

My novel was finally published in 2018 by the American University in Cairo Press’ imprint, Hoopoe Fiction. The sole British newspaper review, in the daily Independent and its i-news, was accompanied by a photo of refugees walking on a beach in Greece. There were soundbites bandied about describing my novel as set “in war-torn Syria.” But my novel was set 40 years earlier, during long decades when there was no war in Syria and the concept of Syrian refugees did not even exist. Before its own war, Syria had provided refuge for Iraqis, Lebanese, Palestinians and before them Armenians and Greeks.

What a British person imagined Syria or the Middle East to be, what he or she thought about us Syrians without ever having set foot there, was still more important than what I or people like had to say. We were subjective, but their opinions were objective. That was the message.

Life is comprised of many attitudes and moods. Fiction and other forms of expression must give voice to all of them, reminding us that life goes on regardless of circumstances. The British also lived through a war, in fact two major world wars, and before that, a good number of wars in the 19th century and earlier. Yet they do not see themselves as victims of war, but rather as heroes and as people who can and do overcome.

Before all the changes that took place in the modern era, the British did not live in a functional democracy. Yet this does not mean that before all those changes, everything that ever occurred in Britain was of no value, that the British had no culture, no laughter, no love, no happiness. Shakespeare wrote all his plays and poems during an era of tyranny.

In Italy, Leonardo Da Vinci produced his genius artwork during the era of the murderous Medicis. The same is true with Voltaire in France before the Revolution. The examples are endless. So why do the British accord this privilege of nuance to themselves and to the European cultures around them, but not to other nations with whom they have a long history of a power imbalance? Can the cause of this be pure unparalleled objectivity, or something else a little more irrational?

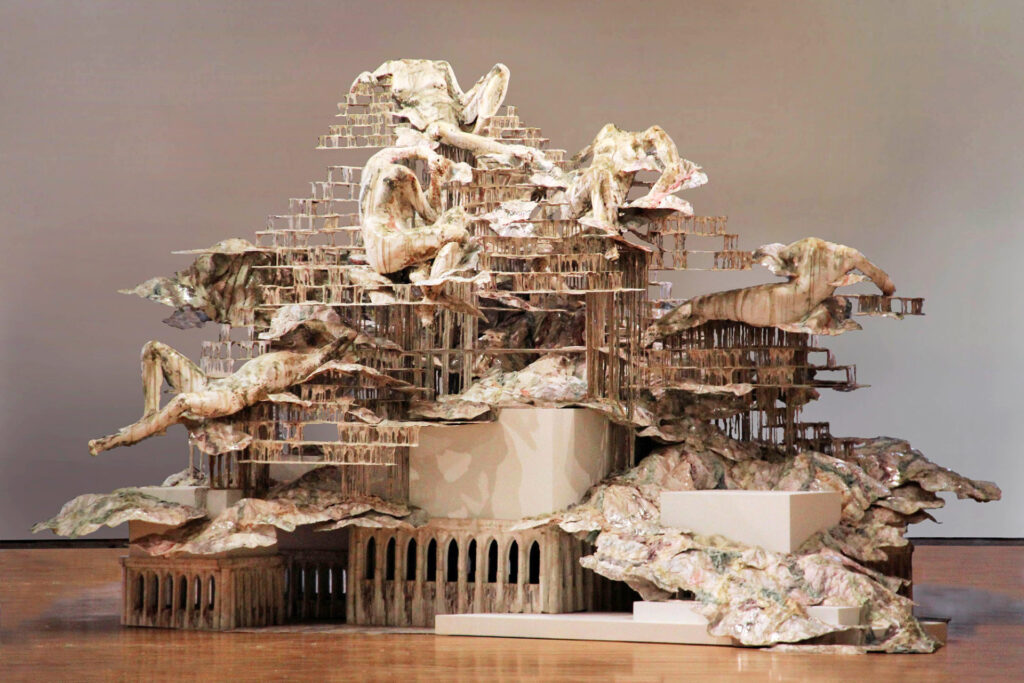

Born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1981, artist Diana Al-Hadid grew up in the American Midwest. She received an M.F.A. from Virginia Commonwealth University in 2005 and attended the prestigious Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2007. Working from her studio in Brooklyn, Al-Hadid is known for a practice that spans media and scale, and examines the historical frameworks and perspectives that shape our material and cultural assumptions.

When the Other is portrayed as different from ourselves, whether by accident or intent, we dehumanise him or her. You can laugh or cry, you can be courageous and overcome, but the Other is always monotone, always oppressed, always tragic. It is you who becomes the savior, often, it seems, by launching justified bombs always presented as some sort of gift or favor to the lucky nations on their receiving end.

This dangerous narrative has been going on and abused in rather glaring ways for too long! And as a side-note, these prolific bombs remind me of the following scenario: a woman and her children are being beaten up by her husband in a terraced house in the east London district of Hackney, where the police cannot gain access to help them. So they contact military officials who dispatch a helicopter and bomb the house, killing not only the abusive man but also his wife and children, as well as the neighbors. After this successful “rescue operation,” the military turns over the house and land to their developer friends, who build new homes and enrich government coffers significantly. Meanwhile they continue to feel rather pleased with themselves for having saved the woman and her children from the violent husband, and they secretly wish them a good life in heaven.

I used to say to some of my colleagues at the BBC: imagine if one day China becomes the global superpower, and the voice of the media is no longer in English but in Mandarin. Imagine that Chinese reporters come to England and cover only a certain type of story from a specific point of view, and commission books about England that only support their media coverage and their foreign policy stance. How would you feel? How would you feel if China also happened to have bombed parts of Europe and had a history of exploiting Europeans and causing chaos for economic gain, as well as installing dictators?

How would you feel if the people who bombed your countries, and had vested interests in the wars that had been waged there since the Middle Ages, were the ones who wrote the books about your homeland and told your story their way? They would thus make it look as if somehow all the chaos was solely your fault and that you had brought it upon yourselves single-handedly. And it would appear as if their only involvement in your part of the world was that of a rather saintly innocent, bumbling savior?

When the truth was anything but.

In a way, the West is putting itself and its own people at a huge disadvantage by refusing to understand others or to see them as they are, while those others understand western peoples so well, and are keen and open to learning from them. A Syrian person (for the sake of argument) who speaks Arabic and English fluently, and understands both East and West comprehensively, is able to see the world with two pairs of eyes. As a result, he or she has access to so much more culture, knowledge and life skills than an average western person. They are learning from you, but you are not learning from them. They know they have things to learn, but you are not aware of all that you could be learning that is lacking in your culture and society, things that foreigners can see but you cannot. Think of that disadvantage and its consequences.

Syrians do have something to bring to you, a gift of something your culture lost some time ago, a deeper awareness of what life and even love are all about. And at the same time, they also have something to learn from you, the gift of a kind of freedom they have never had.

What Syrians like me would like the world to know is that Syria is its people and its culture, Syria is not its dictators, nor its invaders, nor those who covet that land and who are willing to kill its people so that they can get their hands on it. Syria will survive all this, and will outgrow it, just as it has many other tragedies in its long history of destruction, followed always and consistently by resurrection. This is not only a land of death but also of continual rebirth and creation. We mustn’t forget this fact of history. Meanwhile, only art and creation will show the way to a brighter future. We cannot create the future if we forget our past, and forget who we truly are. And remember that Syrians do not see themselves the way western TV screens or newspapers portray them. They know who they are, even if others don’t.

On a final note, this poignant African proverb comes to mind, “Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter.”