Melissa Chemam, columnist

As I anticipated in last month’s column, the EDM festival SOUNDSTORM took place in mid-December in the Saudi capital Riyadh, attracting more than 180,000 participants, despite Covid and its new threat of the Omicron variant. Many in Saudi Arabia celebrated the event as a major success for their diplomacy.

This year, the country also welcomed a Formula 1 competition and an international film festival — it is impossible not to see these events as a part of the country’s soft power and policy to whitewash its terrible human rights record.

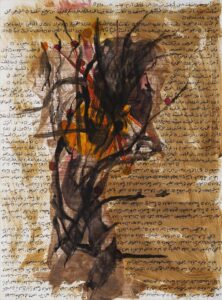

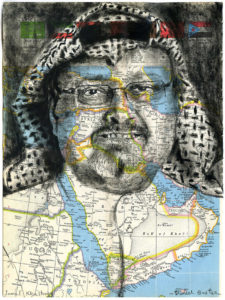

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYSBcOWH5SUFor someone like the Washington-based Lebanese/Dutch journalist Kim Ghattas, author of Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Rivalry that Unravelled the Middle East, it is obviously the goal. During the December 17 British podcast Oh God What Now?, she said that the objective is “to give Saudi Arabia a shiny outside image to the outside world, make everyone forget about some of their past and still present abuses, whether it is women who are still in jail, the murder and dismembering of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Turkey in 2018, and other aggressive foreign policy moves like the war in Yemen. This is all to show the world a different image.”

In a Human Rights Watch opinion about the festival, published on the 15th of December and written under the pseudonym of Arwa Youssef by a staff member, who fears for her/his security, HRW argued, “Global music superstars slated to perform at the upcoming MDL Beast Soundstorm Festival in Saudi Arabia should speak up for human rights or else not participate.” The anonymous staffer went on, “Those performing in the event, which is sponsored by the Saudi government, as well as the influencers who promote it, should distance themselves from the country’s attempts to whitewash its horrific rights record.”

This sad state of affairs unfortunately leaves musicians and artists from the region with very limited freedom to practice their arts in a respectful and progressive environment. On the one hand, the festival has obviously been used by the Saudi government, which invested in it. But on the other, as Kim Ghattas also noted, for Saudi citizens, these events are in part good news, showing that a segment of the population benefits from the ripple effects of this new-found external policy, so they are able to enjoy themselves, and that’s a novelty.

For other commentators, it is the only way for the region to create its own cultural infrastructure. In an article in Music Week, the Tunisian journalist Sofia Guellaty, founder and creative director of creative agency Mille World – an advocate for Soundstorm – explained that with more than 60% of the country’s 35 million population being under 30, a new music-driven culture is emerging in the region, and it should be something to celebrate. “At the core of this has been a government-led initiative to open Saudi Arabia to the world,” she penned, “and more importantly, to show the world what Saudi Arabia is truly made of. I am talking millions of kids who, after years, now have the license to explore who they truly are by being offered cultural content that is unbounded, unfiltered, and, more importantly, authentic and relevant to their own stories.”

Guellaty sees Saudi Arabia as a leader for the Arab world, and an inspiration beyond the Western model. “Here, millions of people who never dared to dream of making it in creative industries are offered incredible opportunities they would never find abroad,” Guellaty added. “And MDLBEAST is one of them.” She concluded: “While I’m not Saudi, I take a huge sense of pride in what’s happening as an Arab, and I want to be a part of this new shift.”

Over the past few weeks, I discussed the impact of this festival with music producers, researchers and other writers.

As I enjoyed the Bristol Palestinian Film Festival, I thought about Palestinian DJs and producers who were some of the pioneers of the scene, from the early 2000s, but could not find enough means to perform at home. Their only way to exist as performers is foreign festivals. Even a singer-songwriter like Kamilya Jubran, who was one of the first to use electronic tools in Palestinian music, ended up moving to Europe in 2002 to be able to pursue her career.

These days, the Palestinian techno queen Sama’ Abdulhadi, who has performed as a DJ all over the world, knows the issue too well. Last year, she performed and shot a music video near a holy shrine at home in the West Bank, near the Nabi Musa mosque. And she ended up being arrested by Palestinian police, then jailed for eight days. The event had been licensed by the Palestinian minister of tourism and was intended to be featured in an international music event to be livestreamed on the music and gaming site for young people Twitch.tv. In the following hours, more than 6,000 people signed an online petition demanding Sama’s release. And her arrest was criticized by human rights groups.

Over the past ten years, artists and DJs like Sama’ have benefitted from the rise of social media in the Middle East, but they still need to either perform or to get funding in order to survive; and these are assets that they can rarely find at home. The electronic music scene benefits from a western business model that has allowed more artists from the Arab world and the Middle East in general to emerge, but it comes with strings attached, a capitalistic enterprise, a money-driven production system. And clearly the Emirates and Saudi Arabia have more financial means than Tunisia, Palestine and Lebanon.

The question is rather, can there be a moral and socially-aware way to produce major music events at all anywhere in the world? And could such a model reach the Middle East? Where does the music come from? Is it authentically broadcast?

Currently neither Tunisia, Palestine nor Lebanon have the infrastructure for major international festivals, but do they even want them?

I discussed this recently with the London-based Gaza-born Palestinian playwright Ahmed Masoud, who offered a stark reminder that Palestinians don’t even have constant clean running water all day or enough electricity, let alone well-equipped venues.

So, one could further ask: is it fair to party when most citizens in such places can barely obtain decent living conditions? And how to keep the arts alive? Of course, spaces for creativity and enjoyment remains crucial, and such spaces are often places where diversity thrives. But they have to go hand in hand with social issues, such as ethical working conditions, access for all parts of society and not only the super-rich, and respect for human rights.

For many engaged artists and activists, the electro scene is symbolic because it emerged from the underground and suburban scenes, as a way to reactivate the Arab sources of modern music. Just like African American music, traditional Arab musicians did influence new movements such as disco and electro. International mega stars like Cher and Freddy Mercury were quite vocal about their origins, in Armenia and Iran respectively, and their interest in non-Western music from Persia or India. And Egyptian musician Halim El Dabh, who later moved to the USA, is considered by many to be the father of electronic music, thanks to his pioneering work in the 1950s in Cairo and in the early 1960s at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. And I’d like to dedicate a coming column to his journey!

For now, what I can conclude is that expansive major festivals are never going to be the most genuine vehicle for authentic Middle Eastern voices and creators. So it is also up to listeners and music lovers to find ways to support alternative music scenes in respectful ways. And these remain to be completely and constantly reimagined.