Despite Ragab's significant contributions to literature in the '60s, he struggled to gain recognition for his work. Many accounts suggest that his unique style and his courage in challenging prominent figures of his time led to him being rejected and overlooked. Furthermore, his impoverished upbringing and his non-Cairene origins may have posed significant obstacles to his success from the beginning.

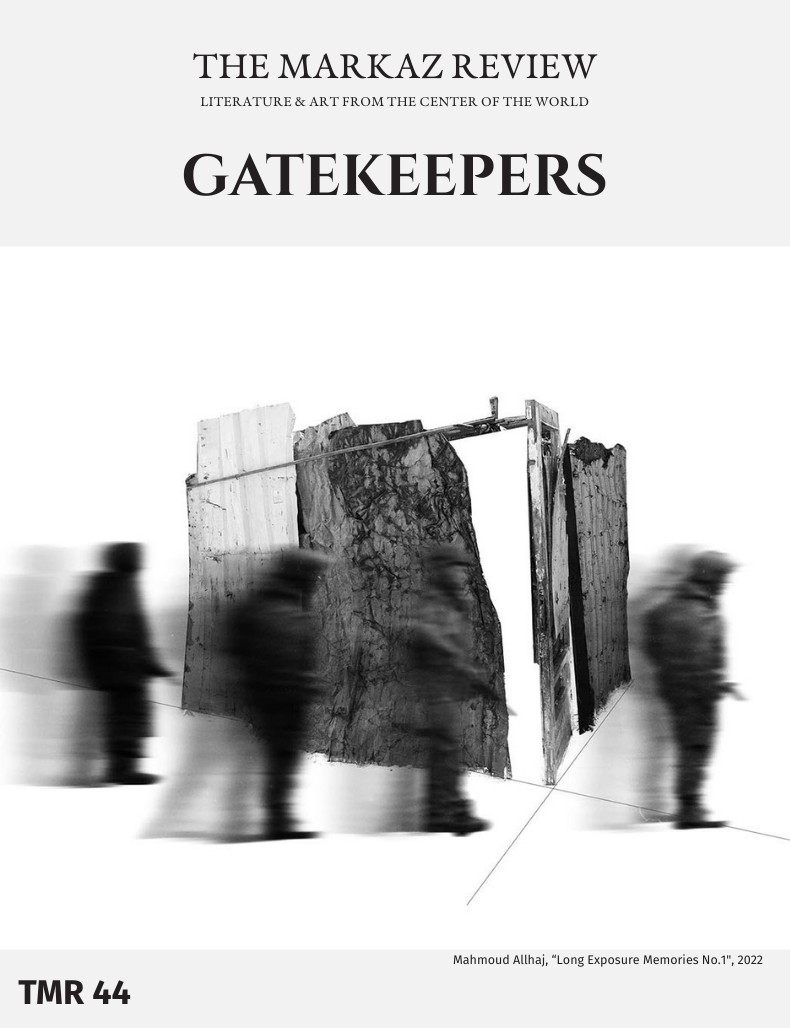

I hadn’t heard of Mohammad Hafez Ragab before his passing in 2021. His obituary described him as the “nut vendor turned great writer,” a fitting title for someone renowned for his statement: “We are a generation of young writers without teachers,” (meaning we are a generation of self-taught writers). Driven by curiosity, I combed the internet to learn more about him. My initial findings exposed a typical story of the center crushing the margins.

The Egyptian writer was born in poverty in Alexandria in 1935. After completing primary school, he dropped out of formal education to work as a candy and cigarette vendor. In 1950, at the age of 15, he established the Cultural Association for Emerging Writers in Alexandria (Rabitat AlEskandaria Lil Nashee’een), after which, in 1956, he founded the Association of Avant-Garde Writers (Kuttab Al Talee’a).

Ragab’s career kicked off when his first story was published in Al-Masaa’ newspaper, prompting him to relocate to Cairo. Working at the Supreme Council of Literature, his unique and pioneering style became increasingly apparent in the stories he subsequently published. However, he found himself at odds with a Cairo that rejected him. He left to Alexandria, where he spent decades living in isolation, dedicating himself to writing.

Ragab received very little recognition during his lifetime. He won the Best Storyteller Award from the Writers Union in 2007 and received relative attention after the publication of his complete works in 2011 by Al-Ain Publishing. I came across press coverage for the book’s signing ceremony, an interview, and finally a discussion about the book months later at the Narratives Lab at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, where he was feted and honored for his contribution to Arabic storytelling.

I am not in the habit of researching writers’ lives until I’ve read their works, but in Ragab’s case, it’s difficult to do otherwise. Legendary tales about the writer surround him, and readers inevitably have these tales in mind while reading his short stories. I’ve read some deeply saddening accounts about his confrontations with Cairo’s “dinosaurs” — the gatekeepers — of 1960s culture. The prevailing online narrative suggests that he was rejected and overlooked not only for his unique style but also for his courage in challenging key figures of his time. However, his impoverished upbringing and his non-Cairene origins were essentially a death sentence from the start.

In 1960, Ragab published a collection of short stories, which he compiled and titled Aysh wa Malh (Bread and Salt), co-written with young writers of his generation. In 1968 he published two further collections Al–Ghorabaa’ (The Strangers) and Al-Kura wa Raas al-Ragul (The Ball and the Man’s Head). In 1979, he published a collection Makhloukat Barrad al-shay al-Maghli (Creatures of the Boiling Teapot), featuring a mix of his old and newer writings.

It wasn’t until the ‘90s that he went back to publishing. In 1992, he released Hamasa wa kahkahat al-Hameer al-Thakiyya (Hamasa and the Giggles of the Smart Donkeys) and Ishti’al Ras al-Mayyet (The Dead’s Head Ignited), which he followed in 1995 with Tareq Layl al thulumat (Night Wanderer) and Raqasat Mariha Libighal Albaladiyya (Merry Dances for Municipal Mules) in 1999. His final collection ‘Ashek Koub Algawwafa (Lover of a Cup of Guava Juice) appeared at the start of the millennium, before his complete works were collected and published in 2011.

I spent days immersed in his writings from the ‘60s and found myself captivated by a narrative that felt incredibly distinctive, especially within the Arab context, even by contemporary standards. His writing style underwent a noticeable transformation after The Strangers, which became especially evident in the subsequent collection, The Ball and the Man’s Head. This stylistic shift persisted in his later works as well. His incredibly intricate images and short sentences leave a bitter aftertaste that lingers in your mind. The stories are so captivating that you can’t help but want to read them again and again.

M. tore tore at his chest releasing his frustration: “Look inside me and you will always find sadness, and yet I still go on. You have not experienced living as a mute, where you walk the asphalt alone for months, without a soul to talk to. You lived with your tongue intact. No one cut it out for you.” — “The Tedious Tour of M.” from the story collection “The Ball and the Man’s Head,” (1968).

However, I often found myself questioning whether my admiration stemmed from sympathy for the writer’s life story or from a genuine appreciation for his writing. It felt important for me to take a step back and distance myself from his work in order to form a more objective evaluation.

Three years after setting aside Ragab’s work, Zawya Cinema in Cairo announced the screening of a documentary on Ragab titled Mohammad Hafez Ragab: The Tedious Tour of M, directed by Hend Bakr (2023). I decided that I would go back to re-acquainting myself with the author’s other works for a more comprehensive viewing experience.

Picking up from where I’d left off reading his second collection, I observed minimal variation in style from his first work:

I shed my name while crossing through the crowds. I carried a book tucked in my bundle of clothes, and dreamed of entering through the doors. Honestly, I am in extreme pain. I do not know how to restore the heat of the fading spark. He who has lost the ability to transmit nostalgia feels nothing but pity for the self. — “Passing Through the Congested Bridge,” from the collection “Hamasa and the Giggles of the Smart Donkeys” (1992)

…

“I was disturbed by a car horn bleating a broken tune. All of a sudden, I saw my friends who’d returned from prison. We embraced, although vacuously and coldly. I shivered as one of them kissed me. I looked into his eyes and found two glass eyes staring back at me. I inserted my finger into one of them, and knocked against it, but my finger still wouldn’t go through. My friend smiled at my surprise:

—Don’t be surprised. Glass has become prevalent in all industries, replacing eyes. Have you not seen this before?

I concealed my tears.

—Allow me to leave. I cannot handle glass eyes, I said —“The Speech of a Defeated Poet,” from the collection “The Dead’s Head Ignited,” (1992).

However, the conspicuous incorporation of religious motifs, references, and symbolism suggested a deliberate exploration and inclusion of God within his more recent writing. “The Stick of the Prophet,” a story within Ragab’s collection “Merry Dances for Municipal Mules,” is based on the tale of Moses. In his final collection, “Lover of a Cup of Guava Juice,” the author incorporates Qur’anic verses and directly addresses political issues by integrating news headlines within the body of the stories:

We witnessed everything. How they tossed our bodies into the deep sea, and then effortlessly transported them from the Ghurbal Pasha supply office to the other in Mina Al-Basal.

—”I am selling my ships and freeing the great sailors who stood with me during this ordeal,” I shouted, while I retrieved my ration card. I was engulfed by an unidentifiable feeling as though I were being asked to kill myself in order to prove my sincerity. I was shocked. Today, the triumph of God and His servant is among the most intricate. As I clutched the ration card, He appeared on the ship’s, clearing the way for us to please Him.

—“May God keep you safe for Egypt,” cried the teacher, Ibn Qabbari.

His words carry weight. He wants me to do a big job for the ships. But it was then that the notion seized me: this is an invitation for suicide, despair, and abject dejection. I took out the ration card and began tearing its cover, piece by piece, and threw them into the stormy sea while I screamed from the deepest, darkest reaches at the bottom of the ocean — “The Valiant Ship Captains” — from the author’s complete collection published in 2011

These stylistic changes were quite surprising and left me wondering about the underlying reasons for the author’s decision to make such significant alterations in his writing.

I thought I might find the answer in the documentary.

2

At the screening, director Hend Bakr revealed that the documentary “Mohammad Hafez Ragab: The Tedious Tour of M” was named after a beloved story from Ragab’s book The Ball and the Man’s Head. Almost three weeks after watching the documentary, I can still vividly conjure the wry expression on Ragab’s face as I struggle to put into words the elements of the film that have stayed with me.

The documentary was filmed in Ragab’s apartment, where he confined himself for 30 years. Bakr captured Ragab’s daily life at 80 years old, showcasing his eating and drinking habits, daily routine, the room in which he spent most of his time, and his midday nap. In the beginning, Ragab appears not to notice the camera, the director, or the audience. The film skillfully switches back and forth between close-up shots of Bakr’s expressive face and still shots of the unadorned house and its walls. In one haunting shot, Bakr strategically positioned the camera in the living room to encompass both his bedroom and an adjacent room, complete with a comfortable sofa and a television. Additionally, Bakr’s perspective often extended out onto the balcony, which served as Ragab’s gateway to the outside world. There is a poignant scene where a train leisurely traverses a canal, surrounded by the lively residential neighborhood that compels the audience to question the authenticity of what they are witnessing, blurring the lines between reality and fiction.

Bakr projected video clips from a famous 1960s TV seminar onto the walls of Ragab’s bedroom, closely observing his reactions. In a particularly striking scene, Ragab sits cross-legged on his bed with his back against the wall on which the seminar is running, appearing as though he is seated among the peers who had once rejected him. The director astutely weaves in videos and photographs showcasing Alexandria’s landmarks, which Ragab had discussed but is unsure if they still exist. Having rarely left his home in decades, he had started to forget what the city looked like.

Throughout the film, Bakr urged Ragab to open up and share his thoughts, yet he seemed to struggle to remember details or find the right words. He would stop mid-narration as though realizing that none of it mattered.

The film did not offer any new insights into Ragab’s life. Additionally, the only other person shown in the film was a writer who was famous in the nineties. It appeared that he was disappointed when he first met Ragab, and in the film, he seemed angry with him. However, the film did not provide any background for his frustration. Where were Ragab’s contemporaries, friends, and family?

In the film, there was one story that was new to me. Ragab shared an incident that happened with Louis Awad at a conference they both attended for the Writers’ Union of the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization in Egypt. At the end of the conference, Awad motioned to a pile of papers he expected Ragab to collect, carry, and deliver to him. Ragab felt insulted and refused to do so. As a result, Awad rejected Ragab’s application when he applied to work for Al-Ahram newspaper.

The director was editing the film when Ragab passed away, leaving her unsure about his opinion. She felt a deep sense of responsibility, believing that the film could shape Ragab’s legacy in the eyes of the world. As a result, she made careful choices to avoid including any content that could be seen as taboo or that might influence how people remembered the late writer. Could the director have functioned as a gatekeeper, despite her well-meaning intentions?

Bakr did not provide her audience with details about her extensive six-year journey with the film’s subject or include dates on any of her shots to illustrate the time lapse and its significance. I only became aware of the prolonged filming process when Bakr engaged with the audience after the film. I think not including this information was a missed opportunity.

3

At the post-screening interview, Bakr explained that the film, which was her debut, was self-produced with the voluntary assistance of supportive friends. She discussed the challenges she faced in getting her film proposal accepted by traditional donor institutions, emphasizing the influence of Western donors and their intermediaries in determining which projects receive support. Bakr emphasized that these gatekeepers have had a frustratingly personal impact on her and on Ragab as they seemed committed to preventing both their works from reaching a wider audience, even after Ragab’s death.

4

I decided to start a research project on Ragab in the context of 1960s literature to understand the literary landscape of that period. I wanted to comprehend the dynamics of the various publications and literary circles, the influence of adults on the younger generation, as well as the impact of political oppression. The cynical Egyptian remark, “The sixties, and how do you know what the sixties are?” echoed in my thoughts each time I unearthed a new piece of information.

I realized that my fascination with the 1960s era was stronger than my interest in Ragab. This reminded me of how people who experienced the June 1967 defeat of the Arab-Israeli war might have felt, and how my generation now feels after the failure of the 2011-2012 Arab uprisings who turned back to study the 1919 Revolution. Sometimes, when faced with defeat, we are compelled to delve into the past when we can’t see a clear path to the future. I pondered over the lessons we could extract from this period. Are there parallels with our current situation? Is there still a way to resist, or have we exhausted all possibilities for forging new paths forward?

5

Since the beginning of the 1960s in Egypt, and even before the June ‘67 defeat, a new generation of writers initiated a revolution against the prevailing literary trends of the time. The new writers rejected the common liberal, nationalist, and conservative Marxist beliefs and writing styles. They came from the lower middle classes, laborers, peasants, and political dissidents. They resisted the existing stories that were full of empty phrases and one-sided characters that didn’t reflect their experiences of oppression and disappointment with the new republic’s unmet promises. They expressed their viewpoint using a stream-of-consciousness style in their writing and avoided using elaborate language and sentimentalism.

Ragab, in particular, took a unique approach to writing his texts by presenting them as composite images, straying from the traditional storytelling structure. Meanwhile, others embraced a bold, in-your-face style that didn’t hold back on graphic descriptions some of which included torture and sex. The older established writers criticized the new writers for their unconventional styles, insisting on traditional story structures and reader preferences. Even though some of the new writers’ works were published in literary magazines, they lacked genuine critical evaluation. Instead, influential figures frequently directed harsh and disparaging criticisms at them. During this time, young people had to print their stories themselves, often in low-quality books, to avoid detection by local authorities. They also published their work in Arab newspapers and magazines without attracting too much attention from the self-appointed literary guards.

During this time, several new and experimental literary groups formed in Egypt. One of these groups was the Unity of Communists (Waw Sheen Collective), which included Ibrahim Fathi and Salah Issa. Another was the Democratic Movement for National Liberation, which included Sonallah Ibrahim. These groups suffered imprisonment and torture, leading them to issue a manifesto against the cultural scene in 1966. Additionally, a group including Ragab and Ezz El-Din Naguib published the Bread and Salt collection in early 1960 and later experimented with the Gallery 68 magazine. Notable figures from this generation included Majeed Tobia, Yahya Al-Tahir Abdullah, Youssef Al-Qaid, Ibrahim Aslan, and Jamal Al-Ghitani.

Sayed Hamid Al-Nassag’s book Voices in the Egyptian Short Story offers a comprehensive exploration of the literary landscape in Egypt during the 1960s. It includes excerpts and summaries of critical articles that provide valuable insights into the era’s literary discourse. One notable aspect mentioned in the book is Edward Al-Kharrat’s characterization of the new generation’s writing as reflective of “a new sensitivity.” Al-Kharrat also introduced the concept of “objectification,” which involves the transformation of a human being into a thing. Within this framework, he classified Ragab and others as being depicted as objects themselves.

What I noticed is that beyond the flowery language, there seemed to have been a pervasive inclination among the writers to claim credit for the emergence of a new trend. They excessively referenced themselves and their peers from the same generation as the supposed originators of what they termed as “seeds of renewal” within the old trend, rather than engaging with the stories in a meaningful way. Moreover, I observed a gradual disassociation from identification with the official institution, which seemed to be particularly significant.

In the early 1960s, Ragab’s work received a significant amount of critical attention, much of which was focused on his now-infamous objectionable statement “We are a generation of young writers without teachers.” This statement led to clashes with the older generation, further fueling the controversy surrounding his narratives. Critics held diverse perspectives on his narrative style. Some described it as surreal or fantastical, while others categorized it within the realm of the absurd. Despite drawing inspiration from the downtrodden class to which he belonged, Ragab faced accusations of being disconnected from reality and accused of engaging in meaningless abstraction. Paradoxically, his stories, derived from his own milieu, seemed to deconstruct reality rather than shy away from it, challenging the traditional notion of narration and confirming the inherent instability of meaning.

The older generation’s established writers often supported the idea of fairness and giving everyone an equal chance. However, the people closest to them didn’t always get to take advantage of these beliefs. As Foucault observed, power is pervasive and manifests in numerous ways throughout society. It’s not confined solely to the ruling regime. Expanding on this, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu proposed that various forms of capital, and thus power, go beyond purely economic factors, although economics did play a significant role in Ragab’s case. These include cultural capital, such as prior education, certifications, or experience; social capital, such as social connections that can provide access to opportunities and resources; and symbolic capital, such as fame and status, which can be leveraged to gain respect and recognition from others. But what about individuals like Ragab, who lack resources and have to rely on gatekeepers for their breaks?

In the turbulent landscape of bourgeois “revolutionary” society, power dynamics were deeply ingrained, leaving a lasting impact on the hopes and aspirations of the era. Those who were in positions of power exerted their influence over others, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural movements of the 1960s. The avant-garde writers of the new generation found themselves facing intense scrutiny, with individuals like Ragab bearing the brunt of this oppression due to his lack of connections and support, as well as being a struggling newcomer to the city. He found himself constantly on the move, alternating between staying at friends’ homes and inhabiting tiny rooftop spaces dedicated for laundry.

The aforementioned sheds light on Ragab’s enduring isolation and stagnation within his social class, which ultimately led to his declining health. It highlights the reluctance of bourgeois intellectuals to acknowledge the contributions of individuals from different backgrounds to the literary landscape, unless they offer extraordinary interpretations that cater to the intellectuals’ egos or align with their existing beliefs to avoid causing any internal conflict.

Ragab championed his unique style in an article he wrote in response to the gatekeepers’ attitudes of the time in which he suggested they “belong to a generation that feels completely unfamiliar to us. Let’s allow the public to make their own judgments. And let us join you on the stage. The one whom the audience applauds will carry on singing… Previous generations didn’t give the current generation the chance to be by their side… It’s true that some of them penned introductions to the new collections… but then they left everyone behind… We were the children of suppressed uproar, with successive bursts following one after another, without receiving support from others. We wrote plentifully and documented with great detail and accuracy.”

6

In his 1884 memoir Confession, Tolstoy openly criticized himself and his fellow intellectuals, even going so far as to label them, and himself, as “madmen.” He observed that the real driving force behind their actions was “the desire to obtain money and praise,” and that they believed the only way to achieve this was through writing books and newspapers.

Tolstoy expressed his discontent with the lack of substantial and critical dialogue among his intellectual peers, noting that their interactions often devolved into superficial exchanges of praise and flattery. He lamented that their conversations seemed to consist primarily of individuals sermonizing without truly engaging with one another, except to offer insincere compliments while anticipating reciprocal flattery and financial rewards. Tolstoy observed a pattern in which these interactions would eventually lead to conflicts and discord among the group. Furthermore, he likened their collective behavior to a chaotic narrative populated exclusively by individuals exhibiting extreme irrationality. Tolstoy recognized that he was part of a privileged class within society, intent on maintaining the lucrative status quo.

7

When analyzing a literary work, it is essential to consider various factors to be fair to the writer and their text. In his 1969 essay “What is an Author?” Foucault emphasized how social and institutional contexts influence the interpretation of a text, rather than viewing the author as the sole source of meaning. According to Foucault, any discussion is shaped by social, institutional, and authoritative forces, including the critical discussion surrounding the writer and how their texts are received, both at the time of creation and later on.

In his important essay “The Death of the Author” (1967), Roland Barthes said that we should focus on the text itself, rather than the author’s intentions and background. He believed that the text is always being created through its interaction with readers, which leads to countless interpretations of any creative work.

This brings us back to Mohammad Ragab, whose work is often overshadowed by the narrative of personal life, rather than receiving a fair critical analysis of his texts. Ragab’s work has often been overlooked in its historical context, leading to criticism and praise being directed at him personally rather than at his ideas. In the absence of a literary critique reference, the prior knowledge of the writer’s background, or what is believed to be his background, and sometimes the personal relationship of the reviewer to the writer, influences the appreciation of texts. This has resulted in a wide disparity in the reception of Ragab’s writings over the years, from the sixties to the present day. As Ibrahim Aslan, a close friend of Ragab, noted in his book The Solitude of the Conquered, many commentators on Ragab’s work have been “true asses.”

8

In commenting on Ragab, Aslan mentioned that the writer suffered occasional bouts of ill health but didn’t specify what the illness was or connect it to his writing. Although I wasn’t sure either, recent comments after his passing suggested that his ‘unique’ writing might have been affected by his struggle with schizophrenia. Ragab wrote many articles defending himself and others from his generation passionately throughout his life. Calling him crazy and dismissing his stories as nonsense is not just insolent, but conveys ignorance. This unfair stigma creates another barrier for Ragab, which I will defend by leaning on the works of the intellectual descendants of Freud.

In their 1972 book Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari criticize Freud’s traditional views on mental illness. They examined psychoanalysis as a way to understand mental illness and as a tool of social repression. They mentioned Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) to explain how desire drives society. Artaud was a French Surrealist poet and playwright known for creating the Theater of Cruelty. This form of theater used strong images and intense language. At first, Artaud was part of the Surrealists led by André Breton. Later, he developed his own ideas. When describing his experiences with mental illness, Artaud saw it as a different way of understanding the world, not just an illness. He thought that society couldn’t understand his unique view of the world.

Ragab defended himself against critics in Egypt explaining that “the traditionalists in Egypt labeled me as insane for my beliefs, while the progressives accused me of being out of touch with the common people… I wanted to have a profound impact on the reader, so I made sure my writing was rooted in reality … During that time, expressing ideas in Egypt had to be done indirectly and symbolically, much like playing a sneaky game. Faced with these constraints, I rebelled and declared my insubordination through my writings.”

9

In the early 2000s, there was an increase in funding for civil society organizations, partly as a response to the September 11 attack. This led to greater support for civil and human rights education in order to address extremism. During that decade, many organizations that had been established in the 1990s grew and new ones were also set up. In Egypt, cultural work became more organized through non-governmental organizations (NGOs), following the NGOization of feminism and activism. However, these organizations tend to have rigid and non-democratic structures that limit non-institutional initiatives.

In the 1960s, despite reports of oppression, there was a lively cultural scene characterized by open discussions of ideas and criticism in various magazines. While I haven’t read everything from that time, much of the current material I come across seems to lack the depth and breadth of genuine criticism.

10

In his thought-provoking book, The Solitude of the Conquered, Ibrahim Aslan shares his thoughts on Cairo and the 1960s. He delves into the deep connection between the city and its people. He writes: “Surviving the ‘60s was a reality for individuals like me, as we were the genuine offspring of Cairo. Our love for the city came from not expecting anything from it and at the same time feeling disappointment and resentment.” In an interview, Ragab offered rare insight into his mindset by saying, “Under oppressive conditions, individuals may feel compelled to silence themselves. In such circumstances, my natural response is to cocoon myself in enduring silence when confronted by unseen forces.”

In the film, Ragab appears for the last time as he eats a lunch of boiled egg, fried fish, and stale cake. The film concludes with a close-up of him attempting to slice the cake with a fork, leaving the result uncertain. Finally, a few brief lines on the screen sum up Ragab’s death, as though echoing the succinctness of his life. Sadly, two months before his daughter’s passing, Ragab lost his grandchild. He himself passed away two months later.

Pingback: Mohammad Hafez Ragab: Upsetting the Guards of Cairo – Maha Al Aswad