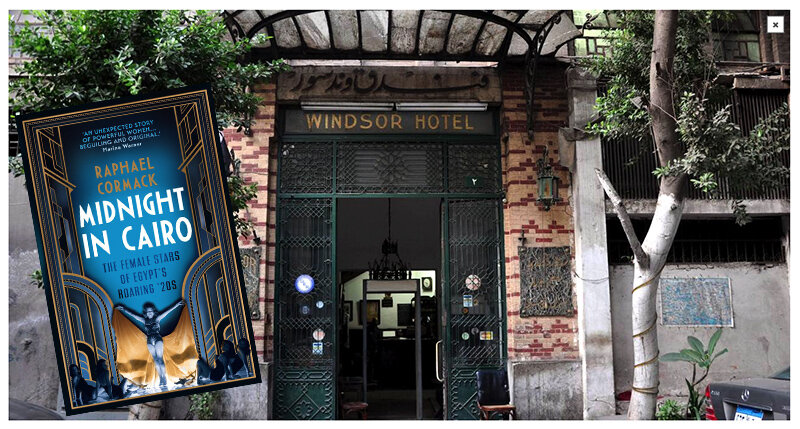

Cairo’s venerable Windsor Hotel enjoyed a revamp in 2010 but retains much of its original 1920s charm.

Midnight in Cairo: The Female Stars of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s, by Raphael Cormack

Saqi Books (2021)

ISBN 9780863563133

Selma Dabbagh

At the center of this book is a street that I sense I have always known existed and where I feel I have always needed to be, but it took a historian like Raphael Cormack to show it to me in all its glory. It has cafés, cinemas, bars and nightclubs that range from the highbrow to the seedy. It is place of glamor and tackiness, poverty, potential, and artistic invention. It combines the louche with the luxurious, the French with the Turkish and the English, the American, the Arab and the African. It’s Cairo’s Alfi Bey Street in Ezebekiyya during the interwar period.

Physically, it is not a street entirely unknown to me. In the nineties, I occasionally went for drinks at the Windsor Hotel, where the bartender would show off his boxing photographs and I would feel like a dramatized, more intriguing version of myself sitting in the dark carved wood chairs by the arched windows — an Agatha Christie murder suspect perhaps? Outside only scant remnants remained from the time-period of the bar; Ezbekiyya had few traces of the party atmosphere of the interwar period that Cormack re-creates in Midnight in Cairo.

Cairo has had many more serious things to contend with since the roaring twenties: getting rid of British rule, putting out fires, encouraging and discouraging revolutions, nationalizing and privatizing, the strictures of peace deals and structural adjustment programs with a government becoming increasingly more repressive to its own people throughout. All this had transformed the buildings and the spirit of the earlier time beyond recognition. The Al Hambra Casino where Cormack tells us the former French Prime Minister George Clemenceau once presented the singer Naima al Masriyya with a bottle of champagne is now a shop for auto parts, for example.

I’m always slightly uncomfortable with the pleasure I find in being in these colonial residues in cities — normally in 1930s hotels — when the city is proud of having rebelled against colonial occupation, but the aesthetics of colonial architecture were designed to attract and to inspire awe, and I am not alone in occasionally falling sway to tantalizing forces of nostalgia. In his seminal work, Colonising Egypt (1988), Timothy Mitchell explains the objectives of urban planners, by quoting the French colonial administrator, Marshal Hubert Lyautey who described the need for two Cairos:

Midnight in Cairo is available from Saqi Books.

“There are two Cairos, the modern, infinitely the more attractive one, and the old, which seems destined to prolong its agony and not to revive, being unable to struggle against progress and its inevitable consequences. One is the Cairo of artists, the other of hygenists and modernists.”

He goes on to quote Frantz Fanon’s distinction between the “the settler’s town, a strongly built town, all made of stone and steel,” and the “the native town, the negro village, the medina, the reservation, is a place of ill fame, peopled by men of evil repute.” The impression from Cormack’s Midnight in Cairo is that this area of Ezbekiyya, for a brief period, provided an intersection between the two worlds, where oppression did exist, between classes, nationalities and genders, but where it was challenged and subverted by the equalizing forces of music, beauty, theatre and sensuality. Cormack focuses on the lives of individual women to reflect on how the lines of battle were pushed back and remolded.

Cormack’s prose style is light, lucid yet measured and he has an eye for colorful anecdotes. He evidently relishes his subject matter, whilst not fetishizing or exoticizing the women he writes about. The style is similar to that of Stephen Greenblatt, author of The Swerve: How The Renaissance Began, telling history as a tale, a series of stories to be recounted with verve; the sources familiar and at hand, but not overly referenced in a way that would detract the reader from the emotional pulse of the characters’ lives and personal quests for freedom.

With a PhD in Egyptian theatre and an evident feminist bent (so gratifying to encounter in a male historian), Cormack divides Midnight in Cairo according to the traditional play structure, of three Acts: “Setting the Scene”, “The Leading Ladies” and “Curtain Call.” The cast of this play is vast and all the parts are leading characters, for they are, as the subtitle alerts the reader, divas of the highest order.

The women (and some men) featured, range from the well-established internationally reknown singers like Oum Kalthoum, to the almost forgotten stars of the stage, like Naima Masriyya, whose granddaughter is now taking it upon herself to resurrect the singer’s name into the annals of history through a project in her name. Asmahan, the subject of several studies, most notably one by Sherifa Zuhur (Asmahan’s Secret, Woman, War and Song, 2000) is not among those to whom a full chapter is dedicated. The final selection Rose el Youssef, Fatima Rushdie, Fatima Sirri, Oum Kalthoum, Munira al Mahdiyya, Aziza Amir and Badia Masabni, is excellent however, as through each one of these stars, the use of different innovations and strategies are explored: journalistic, entrepreneurial, legal, those to do with image formation and brand management, the production of films, the use of the gramophone, the radio and the running of a casino.

An example of one of the seven leading ladies is Rose el Youssef, whose name lives on as a political magazine in Egypt. A gifted vaudeville star who played the main roles in a series of melodramas for Egypt’s main theatrical troupes went on to establish a magazine, which challenged social and political norms (not without resistance, between 1927-1929 of the 102 issues that should have appeared, 62 were banned). Riled by theatre journalists dealing with “nothing but gossip, lies and personal attacks,” El Youssef set up her own magazine, with her name of course — “she was the star, and she was going to call it what she wanted.” Like many of the women in Midnight in Cairo, El Youssef’s aptitude in her professional life was matched by disasters in the personal sphere. She was not alone in becoming a single mother. Fatima Sirri most famously had to pit a complex battle against the father of her child for paternity, possibly thwarted by the father’s mother, Hoda al Sha’arawi, the feminist icon. The reader celebrates her tenacity and ultimate win in the law courts. The formidable Rose al Youssef, also stigmatized by her acting profession — that was seen to be akin to prostitution at the time — was divorced while pregnant and her son, Ihsan Abd al-Quddus, spent his early years apart from his mother, although the two later became reconciled with Ihsan writing for his mother’s magazine. “Fight oppression,” she advised him, “wherever it is, and always be on the side of the weak against the powerful. Never ask the cost.”

The Egyptian singer and actress Munira al-Mahdiyya (1885–1965), photographed in the 1920s. Courtesy the Abushady Archive

In a recent podcast for Bulaq, Cormack explained that his original idea had been to write a biography of the singer Munira al-Mahdiyya. For those readers more familiar with the life of Oum Kalthoum, the subject of Virginia Danielson’s The Voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthum, Arabic Song and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century (1997), and the 1999 Egyptian TV serialization of Oum Kulthum’s life, Munira al-Mahdiyya may appear as an unsympathetic choice of subject matter, for she is depicted as being behind the negative press coverage of the young singer when she arrived in Cairo from her Delta village in the early 1920s. Dramatized versions of Oum Kulthum’s life have depicted al-Mahdiyya as vengeful, talentless and manipulative. Cormack however, casts an admiring light on this enterprising, cross-dressing actress who reshaped Egyptian theatre. There is no doubt however, that al-Mahdiyya loved being in the public eye, attention-seeking being the name of her game, and was as self aggrandizing and mystifying about her private life, as Oum Kulthum was closed — “she was publicly linked to a succession of men, some of whom she married and then divorced, others whose precise relationship to her was less clear.” Her parties were known to attract the political elite and such was her social reach that myths circulated that parliament once held a session on her houseboat.

Politics and these powerful performers were never far apart; if politicians were not guests, political causes could be stridently upheld by performers, from the belly dancer Tahia Carioca, who mesmerized Edward Saïd in his youth, to Oum Kulthoum. The need to distinguish oneself from the rises and falls in kings and presidents being particularly mastered by the latter.

It would glut this review to try to summarize each one of the exuberant lives of the people in Midnight in Cairo, which also includes well-known characters like Youssef Wahbi. Each reader will have their own favorites, as followers of the music scene at the time had sympathies for particular stars, closely tracking their personal and professional careers and the coverage of them. Cormack blends in the gossip with reality, being cautious about the inclusion of unevidenced sources, but mindful of the power that rumor and gossip could play in making and breaking some of these diva’s careers. Also wonderful are the descriptions of audiences, their participatory role and the need for their interaction felt by the actresses and singers, the notion of tarab, or ecstasy being developed between performer and audience, blending the two into harmony.

One of the most liberating aspects of Midnight in Cairo, however, is the depiction of a sense of space, of freedom of action and movement, related in this zone of Cairo in the interwar period. “Egypt is a country where the Egyptians reign, English rule and everyone does as he pleases,” wrote two residents of Ezbekiyya, Billy Brooks and George Duncan, in a letter published in the American newspaper The Chicago Defender in 1923. Having previously been required to play music on bones in a cage with fully grown lions in Belgium, the two African American musicians may well have had their standards lowered by the racism of the time, but a sense of open-ended possibilities, racial and gender fluidity runs through the deeply loveable accounts in this book.

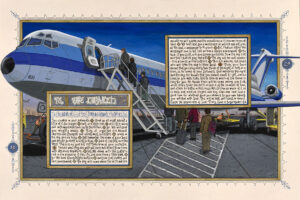

By the interwar period, the vast, rambling Ottoman empire was no more and colonial powers, through the mandate systems and otherwise, were establishing the borders of what were to be the Arab nation states that dominate the region today. Although new restrictions were in coming up everywhere, most menacingly with the building of Tegart’s walls around parts of Palestine, the sense of a relatively unboundaried Arab and European geography is exhilarating to the modern reader, as the musicians toured with their shows to Jaffa, Jerusalem, Beirut, Baghdad and as far afield as South America. These relatively open borders not only allowed for performers to travel, but for others to arrive and with them, new ideas, that were adapted and blended for the appetites (sometimes enforced appetites) of the Egyptian audiences.

In his conclusion Raphael Cormack writes of the stamping out of hope in the 21st century, “for the most part, by those in power.” He goes on to say that “life in the interwar period of the twentieth century remains so seductive because many of its people were convinced that the world could, and would, improve. The women of interwar Cairo who made their way into the limelight were fighting to exert their power and be heard. Their struggles and successes remind us not that things were perfect, but that they can always be different.”

Cormack’s book achieves what deceptively appears to be a modest endeavor, by presenting these women’s lives sympathetically, he inspires us to see how the way to the future can be partially lit by a knowledge of the past. Most of these women started in poverty, few grew up with fathers, but for a time, some until their death, they blazed uncharted trails though a treacherous landscape, through innovation and nerve. Well-researched, even-handed and frequently amusing, Midnight in Cairo is a joy to read during these times where hope is in such short supply. May it lead us to roar through our twenties.