Mexican artists are painting the border wall with the United States to make it disappear.

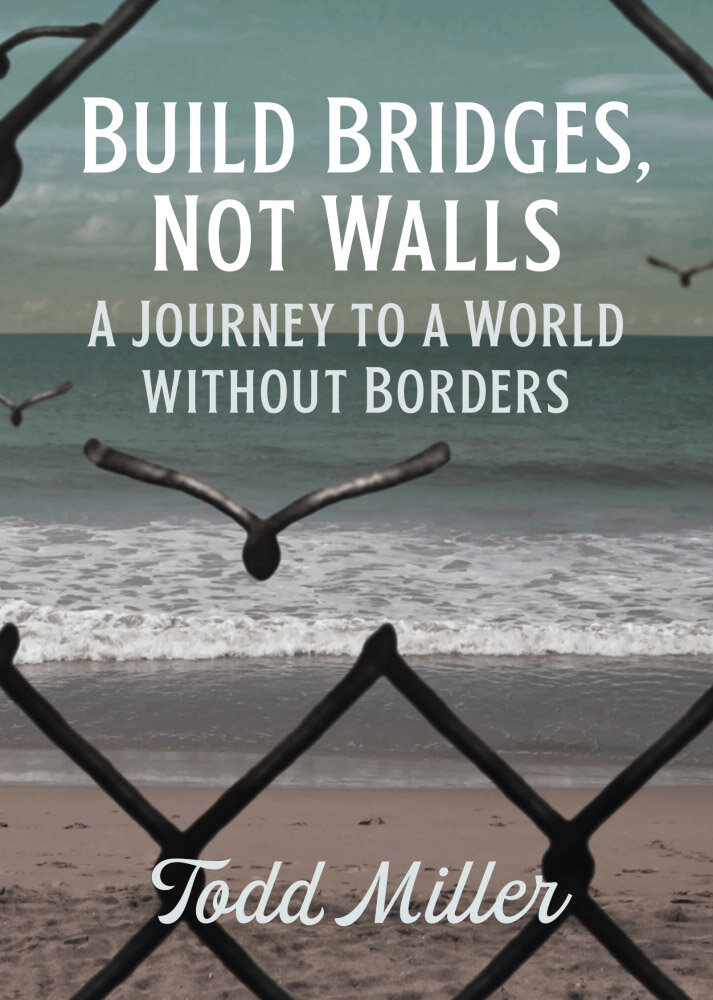

Excerpt from Build Bridges, Now Walls: a Journey to a World Without Borders by Todd Miller

City Lights (2021)

ISBN 9780872868342

Todd Miller

I see a man on the edge of the road. He looks both desperate and ragged and waves his arms for me to pull over my car. We are in southern Arizona, about twenty miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Behind the man is the Sonoran Desert — beautiful twisting saguaros, prickly pear, and cholla cacti — the living earth historically inhabited by the indigenous communities of the Tohono O’odham Nation. As I stop, the man rushes to my side of the car. Speaking in Spanish, he tells me his name is Juan Carlos. He tells me he is from Guatemala. He gulps down the water I offer him and asks if I can give him a ride to the nearest town.

Build Bridges, Not Walls is available from City Lights.

Just an hour earlier, majestic saguaros and elegant ocotillos surrounded me as I hiked out of the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness with Tohono O’odham elder David Garcia. The night before, we had seen two heavily armed U.S. Border Patrol agents monitoring a trail we used to reach the peak of the mountain.

The Baboquivari Peak, where Garcia once fasted for many days to ask for guidance, is sacred to the Tohono O’odham. At points along the path up the slope, we could see layers of mountains extending for hundreds of miles, deep into Mexico. When you are up there you do not see the Border Patrol. You do not see the fleet of green-striped ground vehicles. You do not see the border wall. From up there, the border does not exist. Nations do not exist. The Earth appears as one uninterrupted landscape. Absorbing such a view can alter one’s feelings and consciousness in a way few things can.

Edgar Mitchell was the sixth person to set foot on the moon. He described seeing the large, glowing globe of planet Earth as deeply moving: “It was a beautiful, harmonious, peaceful-looking planet, blue with white clouds, and one that gave you a deep sense…of home, of being, of identity. It is what I prefer to call instant global consciousness.” Seeing the land without political boundaries became an insight into what connects us to one another and the planet as a whole. The revelation was sincere and direct. High in the Tohono O’odham’s sacred territory, I felt something similar to what Mitchell describes.

Parked on the side of the road, Juan Carlos asking me for the ride, awareness of our fractured world comes crashing back. I can’t see the agents, surveillance cameras, and sensors, but I know they are all around. I can feel them. Above, one of many drones in the U.S. arsenal could be documenting the moment and streaming data about our location and movements. Agents are armed not only with weapons and technology, but with laws. One such law forbids me from giving Juan Carlos a ride. Doing so would further his unauthorized presence in the United States. If caught, I could be nailed with a federal crime, a felony. In essence, I could get prison time for showing kindness to a stranger.

But wouldn’t it be a crime to leave somebody there, knowing that doing so could lead to their death? And wouldn’t refusing to help a person in distress due to their ethnicity be racism of the most blatant kind? This sort of racism is encoded into the very concept of “border security” and its regime of agents, technologies, policies, bureaucracies, and violent vigilantes. With no sign of any nearby town, I am forced to contemplate Juan’s skin complexion, his disheveled clothes, and his Spanish-only speech. As one official from the Department of Homeland Security told the New York Times, “We can’t do our job without taking ethnicity into account. We are very dependent on that.”

This is happening in the Arizona desert, but I could have been talking with someone skirting a checkpoint in southern Mexico, or with a person crossing the Mona Strait from the Dominican shores to Puerto Rico in a rickety boat, or with people crammed in a cargo ship going from Libya to Italy or Turkey to Greece. This could’ve been a person crossing from Syria to Jordan, from Somalia to Kenya, from Bangladesh to India, or from the Occupied Palestinian Territories into Israel. There are more people on the move, and crossing borders, than ever before. Approximately 258 million people are currently living outside the country of their birth, a sure undercount given the difficulty of counting undocumented people.

Mexican artist Enrique Chiu (far right) with volunteers, paints border walls and argues for a “world without walls.”

A similar scene could unfold within countries too, since immigration enforcement is hardly limited to national perimeters. In the United States, border enforcement could take place on an Amtrak train in Rochester, Buffalo, Erie, or Detroit, where armed agents board trains and ask people for their papers. We could have been in any of countless U.S. cities where Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents operate twenty-four hours a day, hunting for people who are here without authorization. In Mexico, immigration agents regularly board buses throughout the country. For example, I once saw a man pulled off a bus after he said he lived in San Cristóbal de los Angeles instead of San Cristóbal de las Casas. On another occasion, when I was on a bus in the Dominican Republic near the border with Haiti, an immigration agent asked every black passenger for their papers, but ignored me even as I sat there attentively with passport in hand. And then, in contrast, at the edge of a Somali neighborhood in Nairobi I was stopped and interrogated for half an hour as the immigration agent sifted through my papers.

Now I am in the U.S. borderlands with Juan Carlos, and forced to make a decision. In Build Bridges, Not Walls: a Journey to a World Without Borders, I reflect on why I hesitate when Juan Carlos asks me for a ride. And as I search for an answer, I find that there is a much bigger problem to tackle: Why am I forced to make such a decision in the first place? Why am I compelled to be complicit either with enforcing authoritarian law or with upholding our common humanity, with building a wall or building a bridge?

The book is a journey through more than twenty-five years living and working as a journalist, writer, educator, and perennial student of and in the world’s borderlands. In the process I have met many people who influenced my thinking profoundly —Tojolabal Zapatistas in southern Mexico, a Franciscan friar in the Arizona borderlands, a border crosser escaping the ravages of climate change, an open-hearted Border Patrol agent, and modern-day abolitionists, among many other provocative thinkers and doers in this world who dare defy conventional thought and boundaries.

In Build Bridges, Not Walls I look at the ways that divisions have been imposed, permitted, and accepted over decades, regardless of who is the U.S. president. But I also examine the natural inclination of human beings to be empathic with one another, to forge solidarities with each other, and how such inclinations contrast with the borders that invoke and perpetuate chronic forms of racial and economic injustice. I welcome you to the journey in which you will find a call for abolitionist resistance through kindness — a fugitive kindness that has edge, that shatters unjust laws and is based in solidarity. And you will find an aspiration to create something beautiful, something human, from the broken pieces.