Galleries and cultural venues have reopened, but Lebanon still faces canceled international events due to the ongoing war and evacuation orders.

Although galleries and cultural venues have reopened this week, international events have been cancelled. The Lebanese scene is adapting as best it can to the war situation, despite fear, stress and evacuation orders.

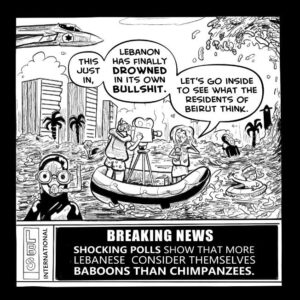

Resilience, did you say resilience? “It’s no longer resilience, it’s exhaustion,” says Lina Kiryakos, director of the Sfeir Semler gallery in Beirut. “It’s an inhuman form of violence. Even if we’re still alive, we’re at our wits’ end. Lebanon is the laboratory of a futuristic war; we’re all part of a game. It’s frightening to realize that this exists.”

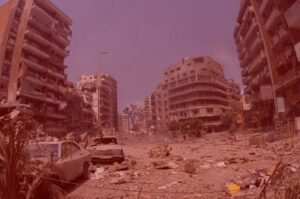

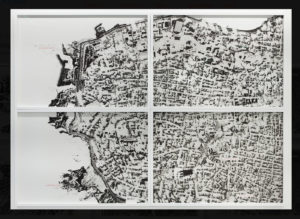

After five years of protests, along with political, economic and health crises, and the explosion at the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, the war in Gaza has spread to the land of the cedars, already on its knees. “As I speak, a drone is hovering overhead, and the southern suburbs are being bombed. Since this morning, there have been 12 evacuation notices. We’re trying to carry on doing our job, but it takes an exhausting amount of energy,” says Lina Kiryakos.

05:10:00, loop (courtesy Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut).

Reality Beckons

In September, when war broke out, the Sfeir-Semler gallery, like all the others, decided to close its doors. But the reopening of public schools at the beginning of November prompted a return to cultural venues. “The rules haven’t been established, but we’re getting a better understanding of the contours of the war,” explains Lina Kiryakos. “We’re getting used to this new reality, even if it puts pressure on programming and opening hours. Our team comes from different parts of the city and we can’t expose them to danger. Despite the situation, people want to keep working, and audiences want to do things that are fun and feel good.”

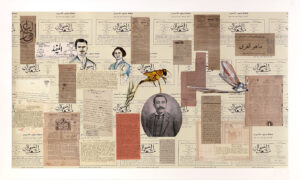

Already this summer, the situation was a heavy one. The gallery, which operates in the downtown area and in the Quarantaine harbor district, had decided to cancel the opening of Walid Raad’s exhibition Festival d’(in)gratitude, scheduled to run from August 7, 2024 to January 4, 2025. “Another exhibition at a threatening historical moment,” stated the invitation. Like many contemporary Lebanese artists, Walid Raad’s works deal with such moments and what they make obvious, possible, probable, thinkable, imaginable and easy to say. His exhibition in the gallery’s two Beirut spaces features both new and recent works.

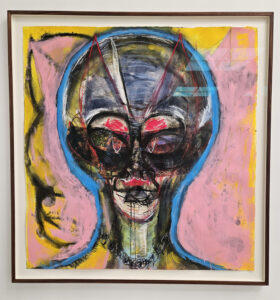

Beirut-based Syrian painter and architect Mohamed Al-Mufti, on the other hand, isn’t working on a new exhibition at the moment. For him, it’s hard to shake off the anger, rage and sense of injustice. “Everything is on hold, for obvious reasons. It frees me from deadlines and pressure, so I’m experimenting a lot, exploring and testing new media, new techniques, maybe new subjects,” he admits.

For most of those working in the arts scene, it’s impossible to look ahead to 2025. Because artists and works are mostly abroad, flights are disrupted and cargo ships no longer arrive. International fairs such as Frieze and Art Basel go some way to filling the gap, as does the presence of a Sfeir-Semler branch in Hamburg. But the gigantic resources put into Walid Raad’s exhibition by this museum-quality gallery cannot be amortized by the passage of collectors and curators to Beirut.

Escape and Meeting Areas

Amid all this chaos, the Nuhad Es-Saïd Pavilion for Culture, a new space dedicated to art and heritage, opened its doors in Beirut at the beginning of November. The National Heritage Foundation, which manages this space, has chosen to remain accessible to visitors wishing to discover its store, café and inaugural exhibition, designed and organized by the Beirut Museum of Art (BeMA), a modern and contemporary art museum in the making.

This new pavilion for culture stands on the grounds of Saint Joseph’s University, alongside the Beirut National Museum dedicated to archaeological heritage, as a space for the protection and continuity of heritage, as well as an affirmation of its influence in the face of the violent destruction and suffering affecting the country.

BeMA co-director Juliana Khalaf recounts how the inauguration, originally scheduled for September 18, had to be cancelled due to the pager attack. “The ongoing crisis situation has multidimensional consequences,” she explains. “In the context of our cultural ecosystem, we must constantly find solutions.” This is the raison d’être of BeMA, created in response to the circumstances of recent decades, which have led to the degradation of artistic heritage. Since 2015, the Beirut Museum of Art has been managing the Ministry of Culture’s collection and restoring some 1,000 works dating from 1890 to 2005, supported by private funds from Apeal (Association for the Promotion and Exhibition of the Arts in Lebanon). In the run-up to its opening in 2027, BeMA is working to pass on conservation know-how, offering training courses in partnership with universities, in particular the science departments which play a crucial role in this field.

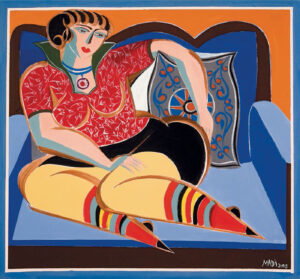

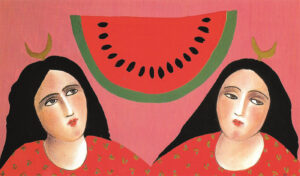

“The important thing is to create public spaces bathed in a culture that unites us,” says Juliana Khalaf. For this inaugural exhibition, BeMA artistic director Clémence Cottard has chosen to exhibit the work of contemporary artists such as Rayyane Tabet, Lamia Joreige, Caroline Tabet and Nasri Sayegh, alongside modern artists from the Ministry’s collection. The theme of the exhibition Portes & Passages, une traversée du réel et de l’imaginaire is linked to the pavilion designed by the Raëd Abillama architectural firm. The public is invited to cross four symbolic passages: memory, myth, perception and territory.

Hymn to Love, an in-situ installation by Alfred Tarazi, questions issues of memory, realities and fictions, the perception of time and space, and a geography rooted in the region. Presented a year ago in a hangar near the National Museum to highlight the lack of interest in the decorative arts — a “neglected aspect of Lebanese museology — the exhibition brings together antique and handicraft pieces designed by the artist’s father in the family workshop first established between Damascus and Beirut in 1860 and destroyed by successive wars. “It’s war that interrupts us, not the other way around,” stresses Alfred Tarazi. “As long as we’re alive, we continue to create because we have no other means of survival, on any level. The public is delighted to see a new space. Culture shows that we still exist.” The National Museum has also reopened, as have dozens of other galleries, as well as the Monnot Theatre and the French Institute of Beirut. “Visitors are flocking in,” says Juliana Khalaf. “Art is a place of escape that reminds us that our culture will never die, a form of resistance.”

A Child of Constant War

The Sursock Museum, a historic monument in the heart of Ashrafieh adorned in the Venetian and Ottoman architecture of the 18th and 19th centuries, closed its doors at the end of October and will not reopen until sometime in 2025. Having just been restored following major damage caused by the August 2020 port explosion, the institution decided to take a break in order to guarantee its mission of accessibility to the general public. The gala dinner planned for December to raise annual funds was cancelled, and solutions must now be found outside Lebanon. “Aid goes first and foremost to the displaced,” says director Karina el-Hélou, who has been crisscrossing European capitals to meet with donors from the diaspora and international institutions.

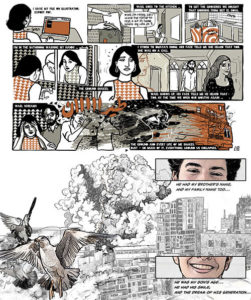

Since the outbreak of civil war in 1975, the Sursock Museum has experienced repeated closures. “We’ve had to adapt to each security and economic crisis, finding last-minute solutions in terms of funding and programming. This teaches us to act quickly with the means at hand to keep going,” confides the young director, appointed in 2022. In response to the massive bombing and destruction in the south of the country, an exhibition of works by the Baalbaki family, originally from south Lebanon, is planned for the reopening. Until then, the museum’s activities will focus on educational initiatives for displaced children, with workshops on modern art led by Lebanese illustrators outside the museum in different venues in Beirut.

On the performing arts front, the Zoukak theater company has also chosen to intervene by helping displaced persons with art therapy sessions in schools and a show for children at the studio, located in the Fleuve district on the outskirts of Beirut. “The cruelty experienced by Palestinians and Lebanese makes us think a lot,” says Omar Abi Azar, playwright and co-director of Zoukak. Every day, the company publishes a “Letter from the Field” on social networks. Open mics are organized at the studio, and all funds raised at events are donated to associations helping refugees. “It’s not a question of adapting, but of rethinking the way we work to meet our belief in the need to be together while we’re still alive,” says Omar Abi Azar, who is keen to point out that Zoukak was founded in 2006 during another war with Israel. In the meantime, the festival organized by the company has had to be cancelled, as have all the international festivals planned for Lebanon.

Since the financial crisis of 2019, Omar Rajeh, director of the international contemporary dance festival Bipod, has been reflecting on how to adapt to different formats by offering interactive performances, creative laboratories and workshops in unconventional spaces. The participation of foreign artists in his next Shift action, scheduled for April 2025 with European partners, seems compromised. “The artists who have stayed in Lebanon feel very alone at the moment. They don’t receive any international support, and this is the time to shine a light on them,” says the choreographer, who has been based in Lyon for several years. “What’s happening in Lebanon and Palestine concerns the whole world. These images of barbarity cannot easily be forgotten. And in the absence of any condemnation, culture is the strongest thing we can do.”

Tom Young, a British artist based in Beirut, highlights that the role of art and culture is to express the unspeakable, to channel unbearable emotions and trauma into something creative which can be a shared experience across borders. “This way, art can be both a mode of healing and processing, as well as bearing testament to unimaginable suffering and injustice. It can also illuminate a positive path forward which cannot be seen now. And, possibly, it can be part of a process which holds those responsible to account. But as we’ve seen with the ineffectiveness of international law, and purely symbolic arrest warrants for Israeli leaders issued today, it is unlikely that the prosecution of those responsible will ever be converted into action. But we will still have the art.”

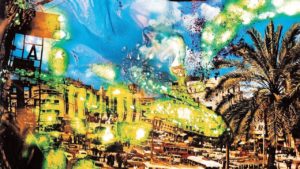

A stunning new museum for the Lebanese sculptress Saloua Raouda Choucair opened in the hills above Beirut, at Ras El Metn this year. Other institutions such as the Dalloul Art Foundation, Saleh Barakat Gallery, and Art on 56th keep opening their doors to the public. Young’s own exhibition Revival at Hammam Al Jadeed in Saida’s Old Souk, which paradoxically celebrates the harmonious history between the three Abrahamic faith communities, remains open daily, despite bombs raining down nearby.

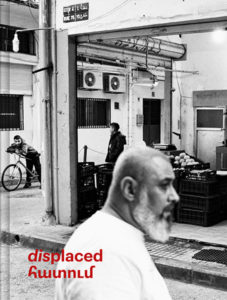

Numerous initiatives testify to the artistic world’s solidarity with Lebanon. Photographers for Lebanon, held on November 14 in Paris, is the latest. Emma Zahouani Burlet, Marguerite Bornhauser, Lara Tabet, Randa Mirza and Yasmine Chemali succeeded in mobilizing some one hundred photographers, who generously offered works for sale, with profits going entirely to the support of families affected by the crisis. At the same time, the Menart Friends association is presenting a boxed set of four photographs created and donated by Guillaume Taslé d’Héliand, a specialist in Near Eastern Roman sites. All proceeds will be used to fund initiatives that help promote Lebanon’s cultural heritage at a time when these historic treasures are threatened by armed conflict.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

Good reading for the art scene in Lebanon. Indeed, in Lebanon art is a matter of survival. Thank you Nada!