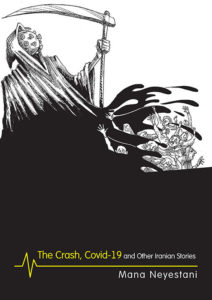

A compelling portrait of a royal lineage whose decline has significantly shaped the contemporary world.

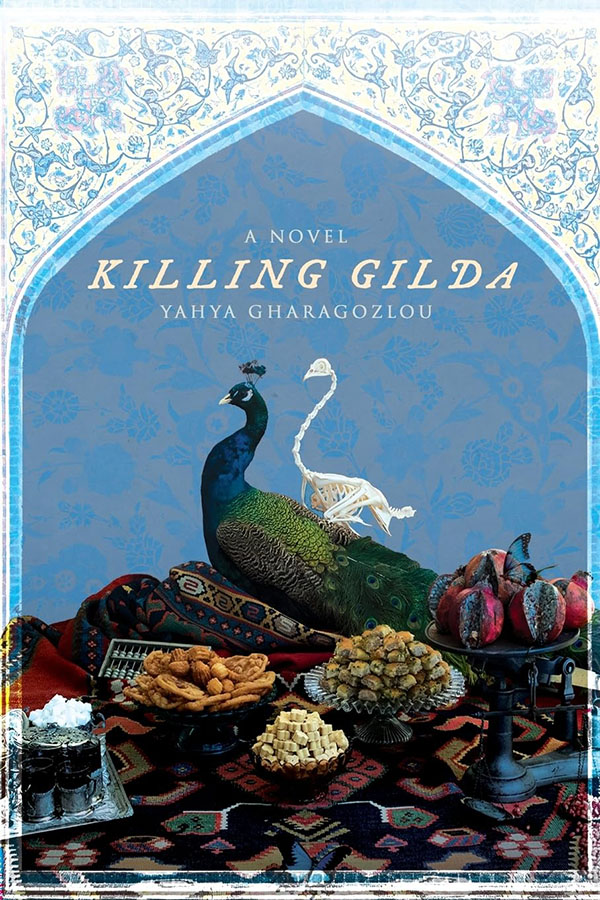

Killing Gilda: A Novel

Armin Lear Press, 2024

ISBN 9781963271409

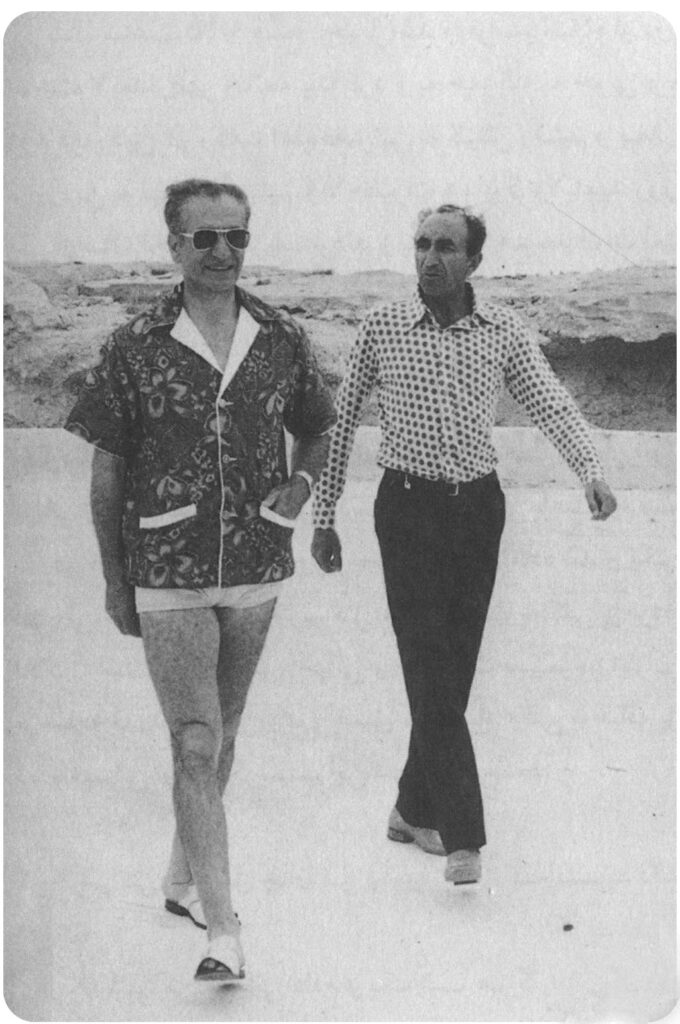

The two of them were a pair, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his Court Minister Assadollah Alam. Forever intertwined by their biographies, bound by duty to crown, unable to get the voice of the British out of their heads, addicted to harrowing high-level womanizing. Alam dressed more elegantly, and was higher-born. The Shah was the Shah.

Their exchanges over the most pivotal moments of Iran’s twentieth century are memorialized in The Alam Diaries, which he recorded daily from the mid-sixties onwards, and dispatched to a vault in Switzerland with some regularity. Alam was the Shah’s only confidant at court, his discreet consigliere and military conscience, his intermediary with the Soviets, British and Americans, his envoy to troublesome minor and major royals, and also his procurer of exquisite women. Their relationship and interactions have been probed for decades by historians, both traditional and revisionist, trying to understand what the Shah was thinking as his reign peaked, tottered and declined, and also to reassess whether the Pahlavi stewardship of Iran was actually more competent, more admirable, and less brutal, than the standard Western media caricature of the seventies and eighties would have had us think.

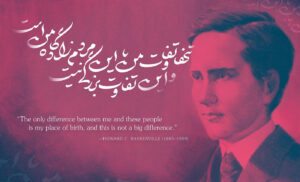

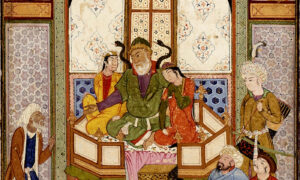

Killing Gilda, Yahya Gharagozlou’s deeply-researched but tonic and playful historical novel, takes up Alam and his nephew as central characters. The nephew, named Samsam but who goes by just Sam, grew up in the Alam household in Sistan and Baluchistan (where his uncle was appointed governor), desperate to become a piano player. Sam aspires to play at Royal Albert Hall, and practices under a portrait of the Queen (not the Queen of Iran, but Queen Elizabeth: the Alams are Anglophiles, or as decades of notes in British diplomatic pouches put it, “friendly” to the British and their interests”). Alam, the uncle, has a sharper sense of how to rule Iran because unlike the Shah, his family had been doing so for generations, minding the country’s sensitive northeast border region while a bankrupt and much interfered-with central government tried to keep control. This lineage, this old intimacy with political power, is what makes the Alams — uncle and nephew both — adept at deciphering foreign agendas and navigating court, reading character and ambitions, anticipating kingly needs; it is also what makes them decisive.

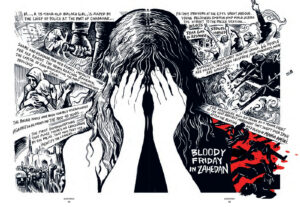

When rioters loyal to the militant Ayatollah Khomeini pour into the streets of Tehran in the summer of 1963, HIM (His Imperial Majesty), as the Shah is described throughout the novel by his advisor, vacillates. They are loyal to a cleric, a man of God, yet they are threatening his kingship. What should be done? Alam, serving then as prime minister, does not brood and hesitate. Let me handle things, he tells the Shah, and if it doesn’t work out, execute me. He means it. “His government flashed metal, borrowed from his backbone,” there is blood, some arrests, but “thirteen years were added to the Persian Empire.” A relieved Alam “drinks champagne and goes to bed with a beauty.” His tactical judgement on behalf of the Shah is vindicated. These episodes in the novel broadly track with the historical record, but Gharagozlou is drawn to the Alams’ interiority. How does it feel to serve a king of whom one often disapproves? To a family of Persian courtiers, to any courtier, to Thomas Cromwell, this is not a meaningful question. “Today a monarchist might look foolish, but not then. We never doubted his legitimacy; his father had won the crown. You buy in, or you don’t. It was just a style of government, a tradition not to be messed with.”

A year after the riots, an assassin opens fire on the Shah on the steps of the Marble Palace. Sam blocks a bullet with his behind and wins HIM’s stiff gratitude. Now he too, like his uncle, has shown the ultimate loyalty, and his reward is to be taken up as a sort of court fool. Not a charmingly disabled or truth-telling fool, but an entertainer who also serves as a private fixer: he juggles, catches plums in his mouth tossed by generals across the throne room, and plays tennis like a jester, lobbing the balls high, to the amusement of the royals who gather on Fridays for doubles or volleyball.

The center of the novel revolves around the turbulent Pahlavi court in the late sixties. The Shah’s household is in disorder: his aspirational mother-in-law is purloining the state silver and monitoring his mistresses; his daughter has become a bohemian religious freak, is often on LSD along with her Range Rover-driving husband (I thought he was a hippie, the Shah muses to Alam, spotting the car), and has built a mosque inside her house. The Shah himself is now middle-aged and married for the third time to the least glamorous of his consorts. He is erotically bored. And his present Empress, in thrall to leftist artists who want to burn down her palaces, fails to offer the steely spousal counsel any leader leads. The entourage around the Shah try to keep up his spirits, vanquish his opponents, and endear themselves to HIM.

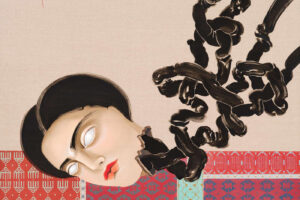

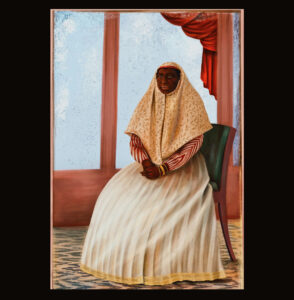

Here the cast conforms with the historical record, and Gharagozlou skillfully brings the court entourage to life, more vividly than in the extant major biographies of the Shah: there is the wise lanky wit Professor Adl, General Nassiri of the SAVAK (the Shah’s brutal secret police), and Davallou Qajar, a touchy foppish courtier (and princeling of the last dynasty) who brokers the introduction to the Shah’s most prominent mistress, Gilda. The Shah preferred blondes, and Gilda, nineteen when she is proffered to the monarch by her parents, is a natural blonde, fair, with green eyes. Her beauty is so extreme that it “had disfigured her life.”

Sam, trusted by HIM to oversee this European side of his life, prepares Gilda for her first royal tryst. Light to no make-up, he advises, and the second person plural for addressing his highness. She asks him, even in bed? HIM is smitten with Gilda, but Gilda is dreaming dangerously big. She wants to become his wife and is foolish enough to say so, in a leaky court. Sam is charged with taking Gilda to Paris for some light surgical enhancements and a reality check. She meets Madame Claude, the famous long-time supplier of extremely presentable blondes to the Shah and much of Europe’s elite. Claude rolls her eyes at Gilda’s ambition. Her girls, or swans, as she calls them, often become the wives of powerful men, but queens? The times are changing, and most are

thickening out to meet the tastes of a new clientele in the Persian Gulf. But a graceful girl like Gilda will always be welcome. Recuperating at a spa in Baden-Baden, Sam softens toward Gilda. Softens enough that when is he is summoned to her modest villa at dawn, back in Tehran, to find her dead of what looks like an overdose, he becomes obsessed with knowing what really happened. Did she take too much cocaine one night, in despair? Had someone heard her floating the intention of writing her memoirs, and silenced her? Had her threat of seeking to marry the Shah reached the ears of someone in a position of intervening?

As news of Gilda’s murder/suicide spreads around the city, the tensions outside and within the House of Pahlavi are growing. The Western press are circling HIM like wolves, and he struggles to contain his rage at their double standards in interviews. Sam fumes at an American reporter, the probably-Ivy League educated son of a CEO, who complains about the Shah living in luxury while some Iranians endure poverty. Can you include a picture of Niavaran Palace, please, Sam asks. Why, asks the reporter. Because “people would recognize it as a modest home in Hollywood.” On another occasion HIM asks a British reporter: does your monarch not live in Buckingham Palace? The old tropes about wily decadent Eastern potentates now shape the coverage of HIM, but adorned in the language of human rights, just two generations out from Queen Victoria and her slave ships.

Killing Gilda fits the contours of a historical novel, but is neither fusty nor ornate nor slow. It is instead acutely consumed with questions of accountability around Iran’s modern predicament: was the Shah really that bad? Why did the country go berserk and commit such an act of epic self-harm? Who is to blame, all these years later, for what went wrong? Why did the HIM, that superstitious, Quran-in-his-jacket-pocket-holding, waffling king, fail to see that the lethal opposition brewing against him came from the mosques, and not the secular leftists? How did he end up, for years, fighting the wrong enemy? Should we not re-examine his legacy, the soaring achievements he secured for Iran, with the failed state, adept only at dispossession, violence, and loss, that has succeeded him?

Alam died in 1977, during the fragile Pahlavi end of times. If he had survived, one school of thought contends, he would have lent the Shah his ruthlessness, brushed off his vegetarian tendencies, and kept 2,500 years of Persian Empire intact.

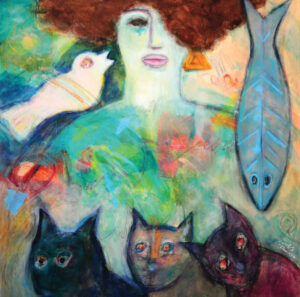

This is a book, in part, of preservation. Like The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, it memorializes the sensibility of people in a place and time that have almost ceased to exist. As events unfold, “the old sclerotic aristocracy of the Qajars watch and grumble from their gardens.” Here is their point of view, the point of view of Iran’s old landed aristocracy, displaced by the British when they elevated a Cossack soldier, Reza Shah, to the throne. “The last Shah took our lands. We retired into our city gardens,” Sam reflects. “The town planners crisscrossed our gardens with highways. Contractors stole our privacy and built high-rises around us. The Islamic Republic hounded us for the last scraps. This aristocracy lost without a fight. No one recognizes the families’ names, not even our American, French, and Swedish children.”

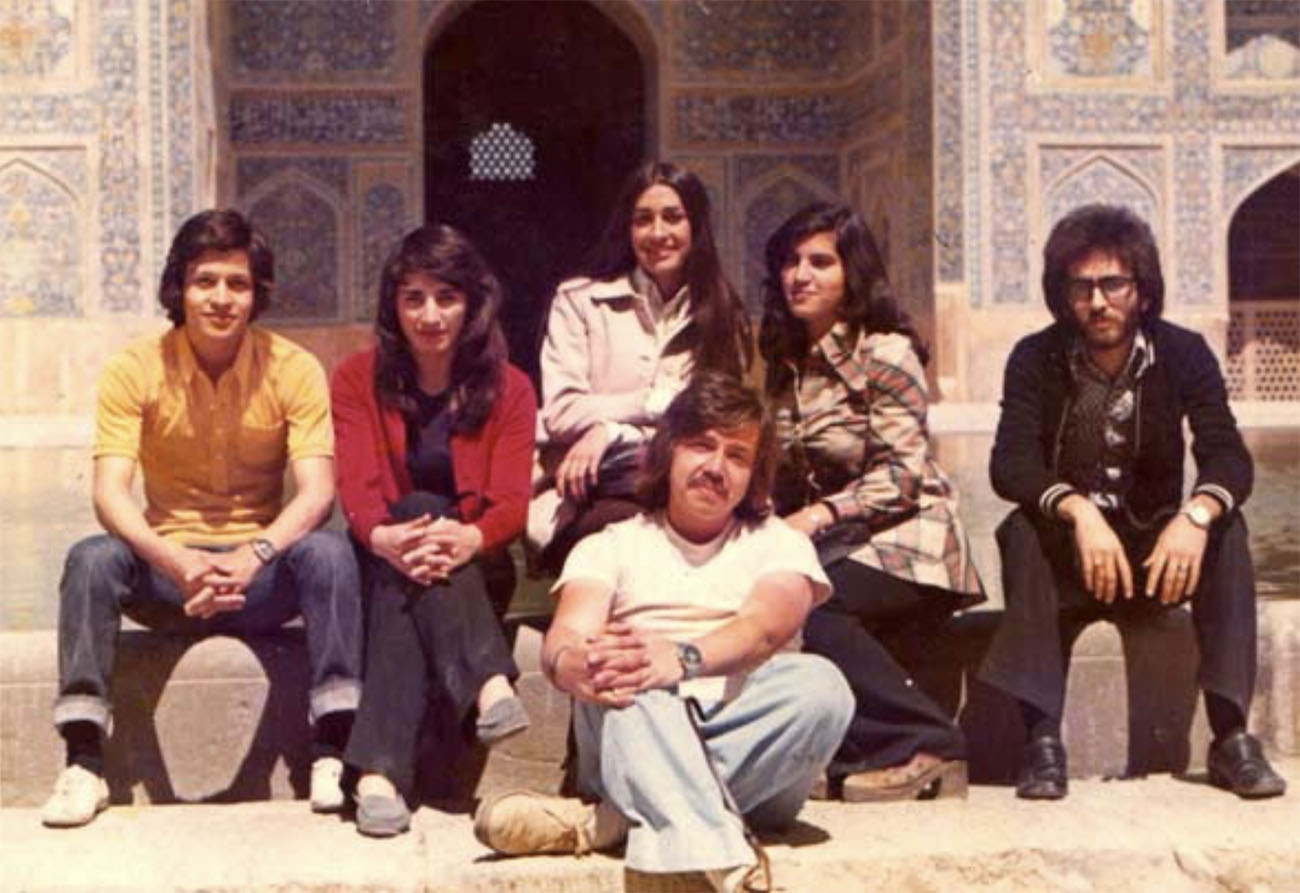

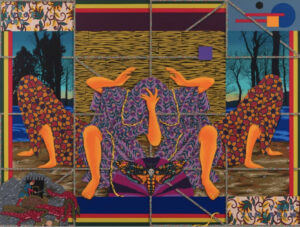

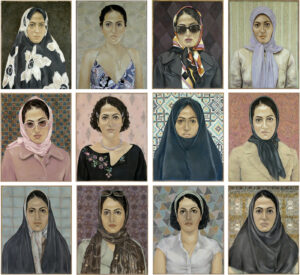

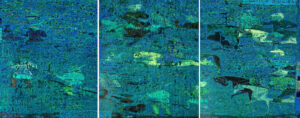

In Killing Gilda, Ghargozlou steps away from the magical realist sensibility of his first novel, and successfully produces a narrative that is both stylistically ambitious and intellectually engrossing. It is rich with deceptively light digressions on encounters between East and West, much like Orhan Pamuk’s My Name Is Red. It is also entirely original: nearly all contemporary fiction written by Iranian writers in recent decades is consumed with post-revolutionary trauma tales of oppressed women or provincial dissidents. There is no novel of manners or period portrait of pre-1979 high society, where various strata, new and old, collided in a country that had been radically transformed in the span of just one generation, in a dizzying social shuffle that was, in a very real way and certainly for the times, meritocratic:

In the late fifties, the wealthy bazaaris, the intermarried aristocrats, the ambitious politicians, and the foreign-educated intellectuals were not a cohesive group, but we intermingled. I hazard a few hundred people ate, drank, and gossiped in cafes, homes and movie houses. If I hadn’t met someone, I certainly knew of them. Re-label and mix each group with the same adjectives of ‘well to do,’ ‘foreign educated,’ ‘ambitious,’ and ‘intermarried,’ and the descriptors fit.

Sam ponders these questions many years later from his perch at a retirement home in the suburbs of Boston. Exiled to Paris after 1979, he spent some years offering his skills (“understanding complex courtly etiquette with nothing-beneath-me service”) to various oligarchs, but grew tired of relaxing his standards and moved to America. He lives out his final years at the home, The Rising Sun, in the company of one Ann Lambton, a relative of the gentlewoman spy-scholar, press attaché at the British Embassy in Tehran, who ran or advised many of the covert British schemes that shaped Iran’s trajectory, from the deposal of the Shah’s father to the coup against Mossadegh. Together, aristocrats of nothing, they watch film and discuss taboo subjects awkward for Americans.

By the end of the book, an overwhelming sense of loss has taken over the story. Piecing together Gilda’s fate, Ghargozlou reflected in the epilogue, was a chance to recreate the milieu or vibe that existed in the twilight of Pahlavi Iran, “A period in which a generation experienced growth and a visual, tactile improvement in wealth beyond anything their parents could have imagined.” He too would have joined the ranks of the technocrats, “all solid, intelligent, and yes, patriotic,” who worked to advance the nation, but for the cracks and upheaval that “destroyed the promise of a nation.”