In making sense of her own relationship to a globally beloved text, graphic novelist Zeina Abirached provides opportunities to experience The Prophet in new ways.

The Prophet: A Graphic Novel by Kahlil Gibran

Illustrated by Zeina Abirached

Interlink Books, 2024

ISBN 9781623716455

Zeina Abirached’s masterful rendering of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet is an exercise in intimacy building. It highlights how, to borrow from The Markaz Review’s March theme, learning to love can be transformative. The Lebanese comics artist, who has resided in France since the mid-2000s, frames her project as both an act of creation and one of readership. In making sense of her own relationship to a globally beloved text with multiple layers of accrued meaning, Abirached provides readers opportunities to experience The Prophet in new ways and to reflect on the nature of reading itself.

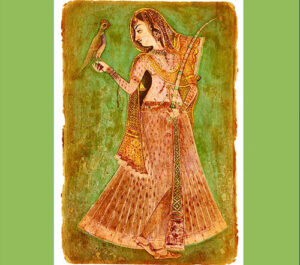

The Prophet is no stranger to new editions. Since its 1923 publication, the English-language prose poem has been translated into more than 100 languages, and it has never been out of print. You can find annotated volumes, vintage copies, and even a full text online through Project Gutenberg. A 2015 animated film of the book, produced by the actor Salma Hayek, constructs new context for the characters and assigns selected prose poems to different illustrators. Abirached’s isn’t even the only graphic novel interpretation.

Gibran is perhaps one of Lebanon’s best-known writers and artists. His most famous text has taken on the weighty responsibility of being “universal.” The text’s ability to reach broad audiences was part of even early marketing strategies, as indicated by Gibran’s friend, editor, and advocate Mary Elizabeth Haskell: “Generations will not exhaust it, but instead, generation after generation will find in the book what they would fain be — and it will be better loved as men grow riper and riper.”

In the early 2000s, the noted dance critic and author Joan Acocella described the ripple effects of Haskell’s prediction. “There are public schools named for Gibran in Brooklyn and Yonkers. The Prophet has been recited at countless weddings and funerals. It is quoted in books and articles on training art teachers, determining criminal responsibility, and enduring ectopic pregnancy, sleep disorders, and the news that your son is gay. Its words turn up in advertisements for marriage counsellors [sic], chiropractors, learning-disabilities specialists, and face cream.”

Acocella’s description of the book’s omnipresence feels more tongue in cheek than the 2023 reflections of the Kahlil Gibran Collective Inc. For the book’s 100th anniversary, the collective credited The Prophet’s lasting popularity to its seeming relevance for multiple contexts. “In a world that seems to be spinning faster every day, the words of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet continue to resonate across time and cultures, providing solace and guidance to millions of readers,” they write on the website. “As we mark the 100-year anniversary of this masterpiece, we invite you to explore its profound influence on the global community and consider how Gibran’s wisdom is more pertinent than ever as we navigate a future of rapid growth and unprecedented challenges.”

The Prophet’s temporal and geographic reach is a monumental accomplishment; as the collective notes, a century of global readership is a feat few texts can boast. And yet universality runs the risk of evacuating any book of its particularities. It’s telling that one of the most in-depth biographies of Gibran is entitled Beyond Borders. Rather than crossing borders, the title suggests that Gibran has surpassed the concept of the border altogether. But then what do we make of Gibran’s real, bordered affinities, movements, and life?

Alienated from The Prophet

Gibran was born in a Lebanon still part of the Ottoman Empire. The Prophet was published just a few years after Mount Lebanon’s catastrophic World War I famine and amidst the development of Greater Lebanon and the French mandate. He was part of the Mahjar Literary Movement, so named precisely because of its members’ migration from Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine to the US. His thinking and work was shaped by an almost 20-year correspondence with May Ziade, the famous writer, feminist, and salon host.

Well after Gibran’s 1931 death, the decade most linked to The Prophet’s popularity — the 1960s — was the same decade in which Arab Americans felt the need to highlight their whiteness or Christianity in order to protect themselves against rampant anti-Black racism and Islamophobia. (Betty Shamieh documents this era of migration in her debut novel Too Soon featured in TMR’s February book club. In it a Palestinian family recently arrived in 1967 Detroit wears visible crosses and brings baklava to their new neighbors; by fostering the assumption that they are from Greece, they move closer to a “White” identity and away from association with figures like Sirhan Sirhan, the Palestinian-born convicted assassin of US presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy.)

The histories of Lebanon, of Arab Americans, of Gibran’s specific Maronite community in Bsharri lie in the background of The Prophet’s trajectory. Rarely named or unpacked in Western discussions of the text, it is no wonder that the very communities in which Gibran was most rooted experience a disconnect when engaging his work.

From her opening pages, Abirached suggests that The Prophet’s “universality” and ubiquity is part of the reason why she, a Lebanese migrant like Gibran, always felt alienated from the text: “I recognized certain quotes, often recited during marriages or ceremonies, and I must admit, this compulsory proximity it had to me, because of where we came from, often made me feel embarrassed,” she explains. “I should know this prophet, and yet … something always kept me away from him.”

For Abirached, it’s perhaps across or through, rather than “beyond” borders during which she comes to experience Gibran’s work. By contrast with the “compulsory proximity” of her initial interactions, sitting down and illustrating Gibran’s words has provided a different type of closeness. Abirached is fascinated by the ways art forms work together to create knowledge and relationship. She describes coming to poetry through music and offers her illustrations as a vehicle through which she might approach The Prophet. “I want to join Gibran’s work in a dance,” she writes.

Collaborative Pedagogy

Abirached’s preface suggests that her target audience is one at least familiar with The Prophet. Gibran’s text introduces Almustafa, who has spent the past 12 years as an outsider in the city of Orphalese. On the day his ship arrives to return him home at last, the city’s residents gather to learn from his wisdom. Each of the collection’s prose poems responds to a theme proposed by one of those residents: “Speak to us,” they say, “of children, of work, of joy and sorrow, of freedom, of self-knowledge.”

The people have gathered to learn from Almustafa before he departs. As he shares his insights, though, he emphasizes that what he knows comes from long and careful observation of a community he experiences from a necessary distance, an attention described by the seeress Almitra. “In your aloneness you have watched with our days, and in your wakefulness you have listened to the weeping and the laughter of our sleep,” she says.

Though Almustafa is The Prophet’s primary speaker, he emphasizes over and over that the knowledge he shares has been co-created with the people of Orphalese. Teaching, he says, is the act of “leading you to the threshold of your own mind.”

One of The Prophet’s most distinctive features is its many paradoxes — the teacher does not share his wisdom but rather helps students find their own. One experiences joy by recognizing sorrow, and love by letting their children go. Freedom emerges when one surrenders the struggle to free oneself. Almustafa’s guidance is less moralizing than it is a call to a reorientation. It pushes the listener toward deepening self-knowledge and a renewed awareness of their connection to a larger community. It’s not surprising that the book was particularly popular in the 1960s’ countercultural movements. On reading Abirached’s illustrated The Prophet I heard unexpected echoes of Paulo Freire’s 1968 Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a now seminal treatise that draws from postcolonial theory and Marxist thought to propose a co-creative relationship between teacher and student that results in collective liberation.

Abirached heeds Almustafa’s call by taking ownership of her own learning process. Her project is not just to receive The Prophet but to sit as a companion or collaborator alongside it. Arts-making as relationship-building is central to Abirached’s work. She is most famous for her graphic novels I Remember Beirut and A Game for Swallows, both of which come to terms with life in the capital city following the Civil War. Abirached explains that “I realized that I had to get to know the city after the war,” a motivation that characterizes her work as a new form of knowing. Here, too, she is after a particular kind of knowledge steeped in relation.

Artistic Rhythms

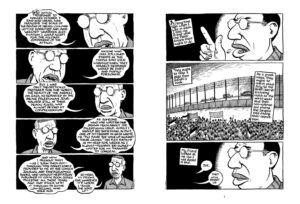

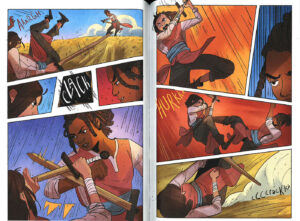

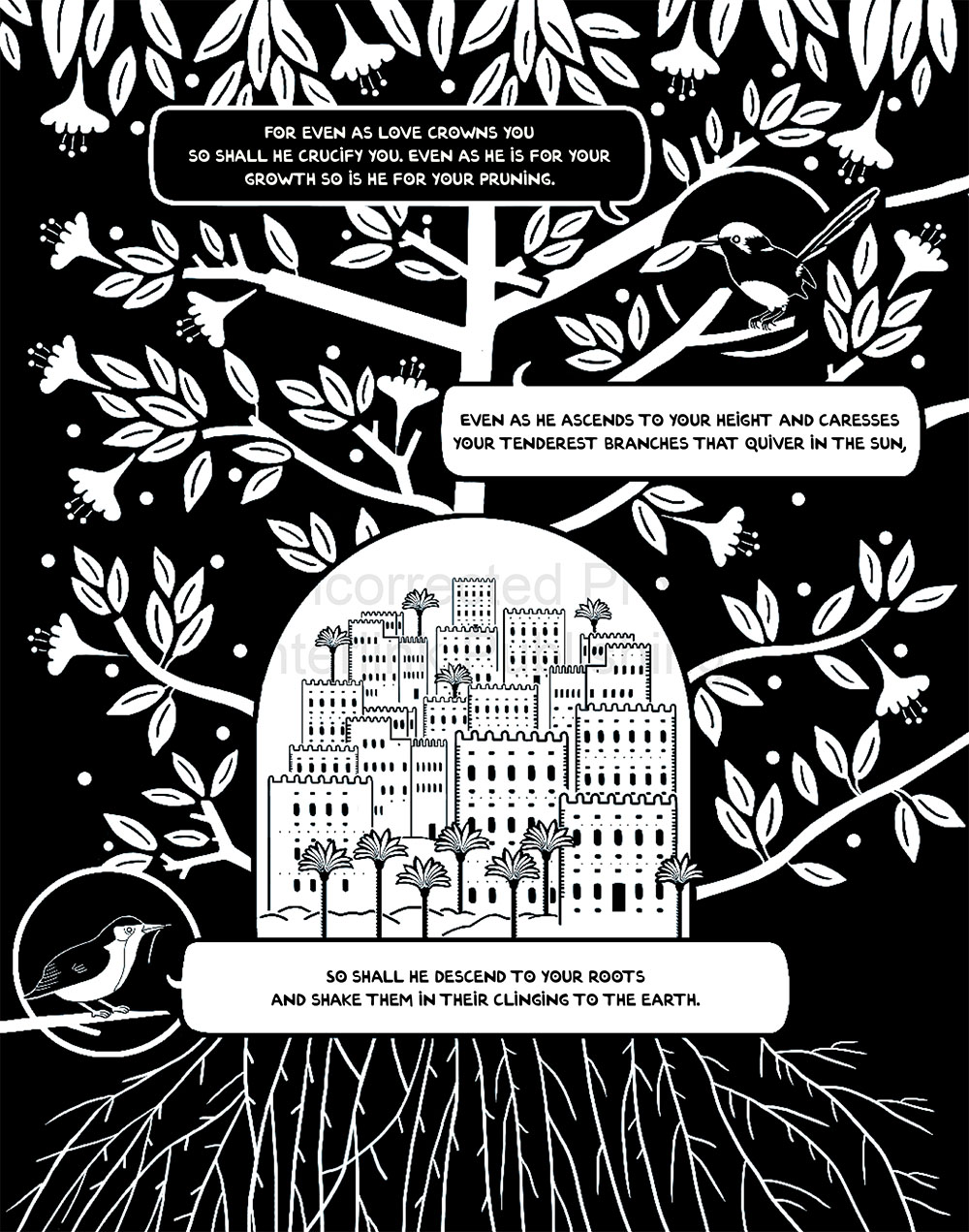

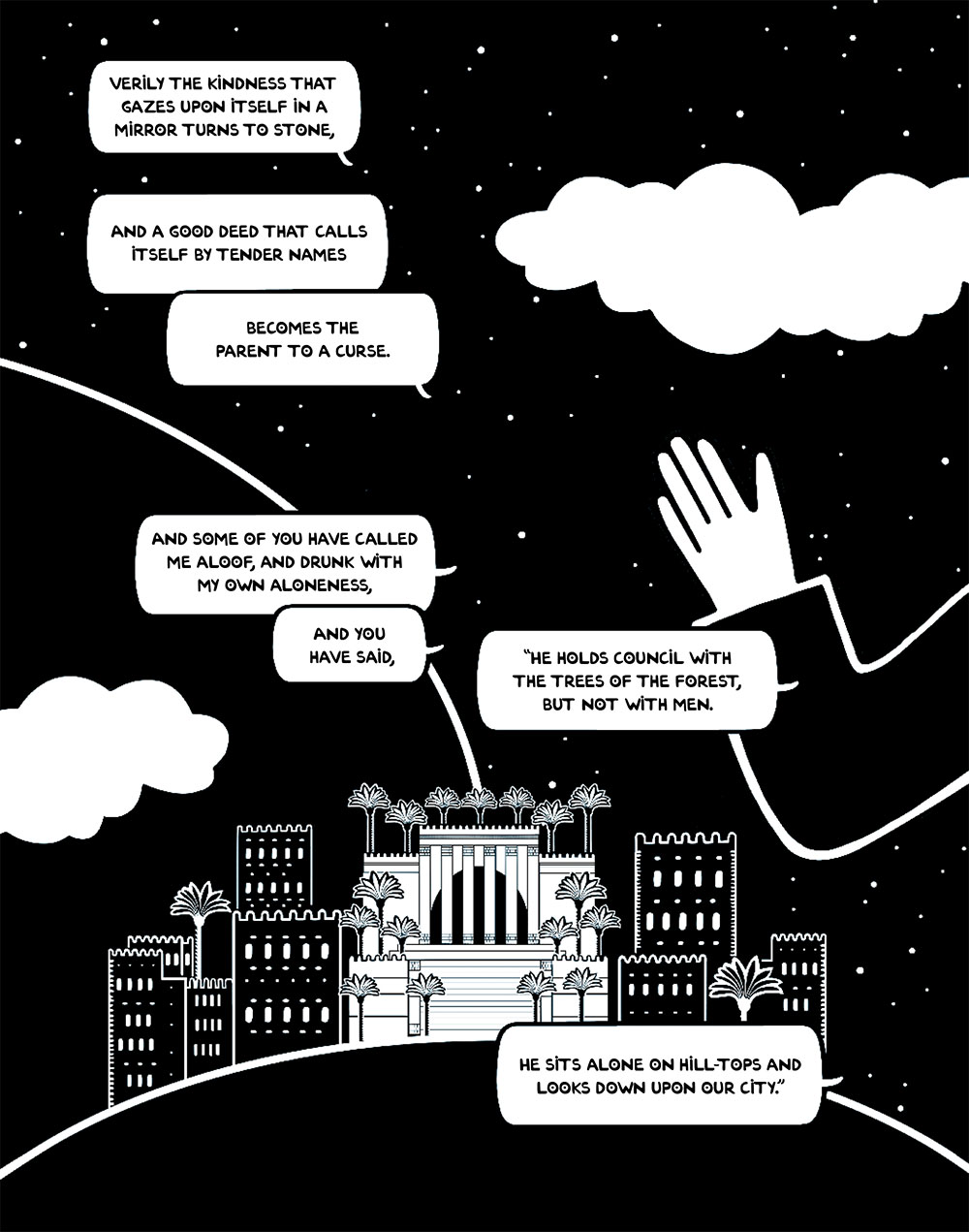

One of her most effective strategies is the way in which Abirached pulls the poetry apart, using her illustrations to alter the pace and rhythm of the language. Each page of her edition features only a few captions at most, and each block of text is short. Flooding the language with image and design has the effect of slowing the reader down. Rather than taking in each section as a comprehensive whole, her illustrations force us to take The Prophet one phrase, one idea at a time. It’s a valuable way in which Abirached’s artistic practice reinforces sustained attention.

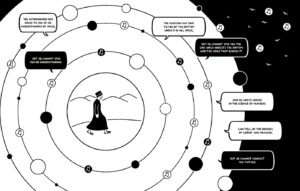

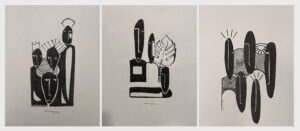

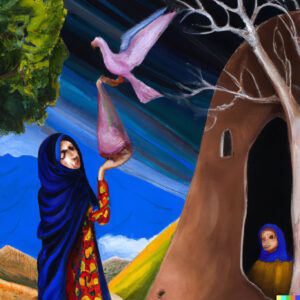

Throughout the volume, illustrated entirely in geometric black-and-white, Abirached’s images echo The Prophet’s description of the individual as part of a larger whole. Almustafa’s face, and those of the people of Orphalese, appear as motifs alongside dandelion spores and birds. Abirached situates the speakers within the planet’s abundance, up to and including gorgeous renderings of the cosmos. Other recurring motifs like musical notes and letters from a variety of linguistic traditions speckle the pages, teasing out the rhythmic and repetitive elements of the original. Abirached’s visuals set Almustafa’s words in motion — they take flight, reverberate, spiral, and settle among the stars.

Her rhythm works against a particular urgency threaded through The Prophet, at least when we read it in full rather than pulling it apart piecemeal. Almustafa bequeaths his knowledge at the dock while a ride home waits for him. Departure is a reality, and these are his last words (even though he talks about return and a re-echoing). Without page numbers and with a table of contents cleverly embedded in the book’s final pages, Abirached’s edition of the work is not easily excerpted. It exists for us to sit in and sift through, always with the impending sense of Almustafa’s departure.

Through these strategies, Abirached’s graphic novel is less an illustrated version of The Prophet and more a translated one, a fitting contribution to the global canon of Prophets. Gibran himself was deeply attuned to the translation process, particularly when it came to the book’s translation into Arabic. He wrote the following to his Arabic translator, Antony Bashir, in 1925:

Your translation of The Prophet is an act of kindness towards me that I will gratefully remember as long as I live. My hope is that the readers of the Arabic language will appreciate your literary enthusiasm and afford it its due worth. In my judgment, the translator is a creator, whether people acknowledge this or not. As far as I am concerned, the most deserving of all people to write the introduction is you because he who spends days translating a book from one language to another is certainly the most knowledgeable of all people about the merits and shortcomings of that book.

Gibran might as well have been writing to Abirached a century later. It is a series of acts of love, to cede your own creation to another thinker, to be the receiver who engages that creation with tenderness and new insights. As Almustafa boards his ship home, Abirached’s rendition of this slim, verbose text gives way to silence. We are confronted not with language but with a true “moment of rest upon the wind.” In this version of The Prophet, Almustafa, the people of Ophalese, and even Gibran are all becoming something new.

The magic of Abirached’s work is the way it lets them go.