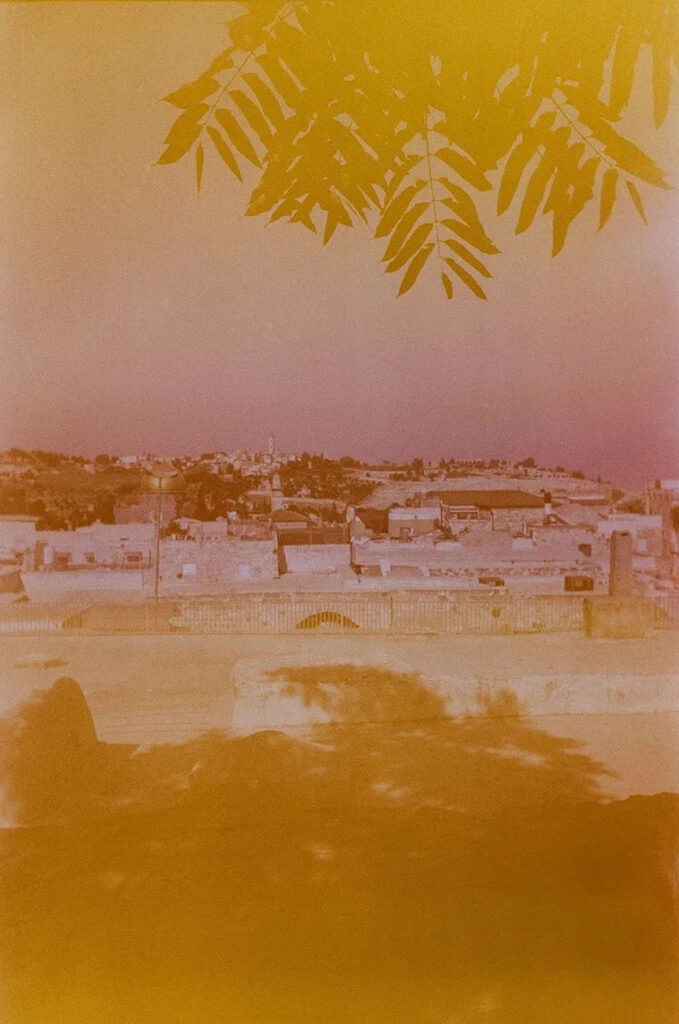

In my last few weeks in Palestine, I purchased a film camera from an antique shop in Gaza and some rolls of film in Ramallah. I photographed different parts of Palestine — Haifa, Jerusalem, Lifta, Ramallah, and Gaza. Because the camera traveled with me through many Israeli checkpoints, the film got x-rayed and the photos turned out grainy, but still legible. The images struck me as an allegory for Palestinian resistance — continuously bearing the weight of occupation, but still very much alive, vibrant, and colorful.

Anam Raheem

My favorite part of taking a photo is that little space between being struck by a moment and lifting the camera to eye level. The space where the seed of awe is planted before sprouting into inspired action. Photography is a microcosm of Mary Oliver’s instructions for living: Pay attention. / Be astonished. / Tell about it.

I moved to Palestine in 2017 for a job with an international aid agency and stayed for five years. As my time abroad was winding down, I bought a film camera on a whim from an antique store in Gaza. I carried it with me everywhere, a balm for the sting of separation. Photography has a way of stretching time. A fleeting moment of beauty – paused, elongated and re-lived through a viewfinder. And then, immortalized with a satisfying click.

The camera traveled with me on my weekly commute in and out of Gaza, passing through the lengthy inspections and harsh x-rays of Israeli checkpoints. I had the film developed when I moved back home to New Jersey in 2021. The photo lab attendant was apologetic when I picked up the prints: The pictures are grainy. The film must have been damaged, like it was x-rayed or something.

I opened the envelope, bracing myself for unintelligible photos. What I found were images that looked so much older than they were in reality. The photos unearth conflicting feelings: the dreamy haze evokes a mysterious romance, a mirror for the surrealism of memory. They also summon a deep sorrow for a land and people held back and worn down by a merciless, unrelenting force. Throughout it all, these pictures send me time traveling – repatriating my past self and dropping back into the quiet, subtle moments that comprise the first commandment of living — pay attention.

When I sit with the conflict stirred by the photos, I hear the words of the late Mourid Barghouti. In his memoir I Saw Ramallah, he documented his return to his birthplace of Deir Ghassaneh after 30 years of exile:

I used to long for the past in Deir Ghassaneh as a child longs for precious, lost things. But when I saw that the past was still there, squatting in the sunshine in the village square, like a dog forgotten by its owners — or like a toy dog — I wanted to take hold of it, to kick it forward, to its coming days, to a better future. To tell it: Run.

Everything false I know about Palestine I’ve learned from politicians and pundits. Everything true I know about Palestine I’ve learn from its people and poets. More precisely, every truth I experience for myself about Palestine, I find reflected in the lives of its people and the words of its poets. I read because it anchors my belonging in the communal experience of loving Palestine. I write because it buoys my hope through the sustained grief of loving Palestine.

A devotion to Palestine, I’m learning, requires a tolerance for the middle seat between enchantment and heartache. Dissonance is everywhere, stacked and layered within a single breath cycle. I stand by the sea in Gaza. On the inhale, it is liberator, a promise of freedom and a respite from densely packed cruelty. On the exhale, it morphs into captor, the horizon barrels toward the shoreline, revealing itself as yet another prison wall.

In a few days, I’ll return to Palestine for my first visit since leaving two years ago. The anticipation of an imminent trip brings clarity to these past two years of separation. It’s been the space between noticing and capturing, the space where attention is alchemized and astonishment sets in.

I am an American with Pakistani roots. I have no ancestral heritage that connects me to Palestine. In a land where the very idea of home has been under siege for Palestinians for nearly a century, I am hesitant to call this trip a homecoming. And yet, referring to Palestine as anything less than a home is also a disservice.

Home is a devotion to the people, places, and practices we are called back to throughout the many lives we lead in a lifetime. Home is in ritual, repetition, and return. It’s where we lose and find ourselves, the transformation of subject into muse. In a few days, I’ll physically return to Palestine, but the truth is that I’ve been there all along. Palestine turned me into an observer and a writer, returning daily to the blank page out of a commitment to understand, inching up a mountain that has no summit. These returns are where I reckon with my attention and astonishment, and as the instructions command tell about it.

I look at these photos again under the light of imminent return. No longer relics of the past, these memories become promises of a near future. I use my imagination to dissolve the hazy tarnish. I’m left with images of joy, beauty, togetherness, and peace — unencumbered. I enter into a collective dream for a future that both honors the past, and transcends the conditions of the present. A devotion to Palestine, I’m learning, requires a different perception of time, one where the rigid linearity of past, present, and future softens and folds into itself like a spiral. In the same vein, I dissolve the illusion of separation between attention, astonishment, and telling. What’s left are a magnificent blend of colors, ink melting onto paper, forming images of a home to which to return.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

It is admirable to have the sense and sensibility to pay attention first and foremost to the very ethos of what differentiates right from wrong; and then to tell about it to others as an ally of justice. Such compassion is very near and dear to God, who is the most Merciful, the most Compassionate, and the most Just.

🙏🏼💕

This was so beautiful and I was especially moved by the surrealism created by surveillance. Thank you for letting us in on this piece of your experience.

Thanks for sharing