TMR and PEN International

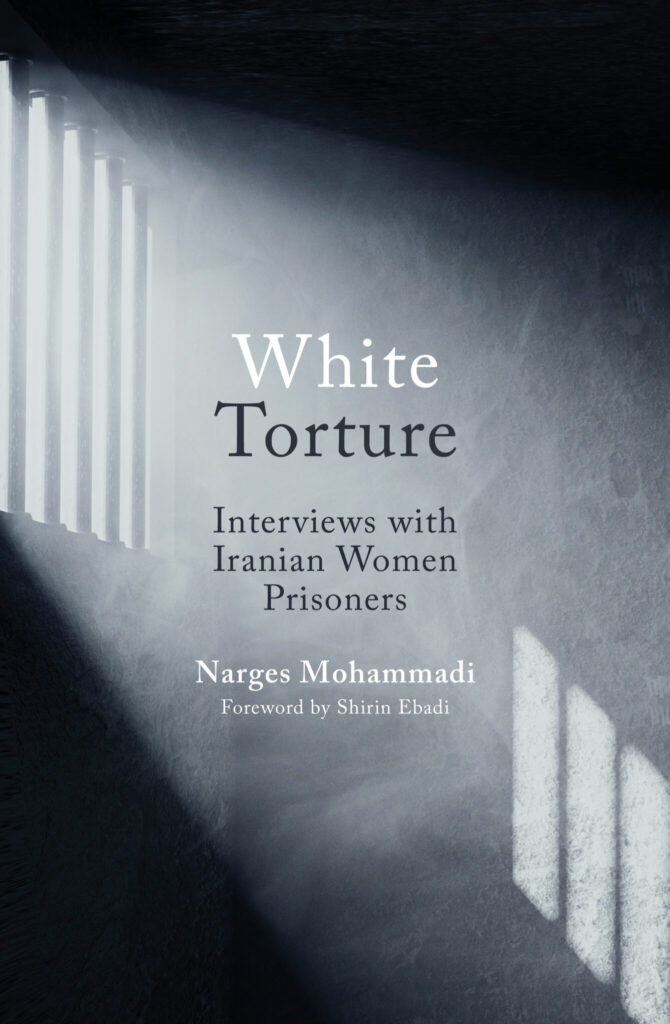

Narges Mohammadi, Iranian writer, journalist and human rights defender, is the author of White Torture: Interviews with Iranian Women Prisoners, a new book from Oneworld Publications.

Arrested and arbitrarily imprisoned on several occasions over the past years, she was imprisoned at Evin Prison in May 2015, and in 2016 sentenced to 16 years imprisonment on several counts, including for “taking part in assembly and collusion against national security” and “spreading propaganda against the state,” in relation to her human rights activities. In October 2022, PEN International learned that Mohammadi was sentenced to another 15 months in prison, followed by a two-year ban on travel. In addition, prison authorities issued a two-month ban on phone calls with her family in Iran as a punishment for her leading role in organising protests in prison in solidarity with the protest movement that swept the country following the death of Mahsa Amini.

According to her family, Mohammadi is now facing a total of 10 years imprisonment, 150 lashes, and a 12 million Iranian rial fine (approximately £250) in addition to the restrictions imposed earlier this year. Mohammadi suffers from a neurological disorder that can result in seizures, temporary partial paralysis, and a pulmonary embolism for which she is said to be denied essential medication. PEN International calls for her immediate and unconditional release. It also calls on the Iranian authorities to ensure Mohammadi’s physical and mental well-being, to grant her full access to all necessary medical care as a matter of urgency.

Siri Hustvedt

Dear Narges Mohammadi,

I am writing to you with mingled feelings of humility, awe, and rage at what you have endured. I have never been arrested, imprisoned, kept in solitary confinement, beaten, or sentenced to flogging for speaking and writing what I believe. I have been able to protest, speak out, and write freely. I have not been forcibly kept away from my beloved daughter and husband or refused medicine for an illness. I do not know how I would respond to such torture, nor do I think any person can know—not until she must face it. I know only that when I imagine these blows, I recoil in horror.

And yet, despite lengthy prison sentences, continual harassment, and torture, you have for over two decades held fast to the right to free expression, have served as Deputy Director of Iran’s Centre for Human Rights Defenders, championed other imprisoned writers and intellectuals, collected the testimonies of women tortured in prison in a book, opposed the death penalty, and asserted the right of the people to protest their government. I and countless others stand in awe of your commitment.

I read an interview you gave on June 4th, 2021, and ever since I have been haunted by your answer to one of the questions you were asked: Why has the judiciary acted so harshly against you? You said, “Mainly because I am woman who does not give in.”

Your refusal to give in and shut up makes you a threat, a threat that extends far beyond the borders of your country. When male authorities, masked with claims to legitimacy by God, nature, or the law, realize they cannot ridicule a woman into silence, crush her with shame, or force her to submit to their will, a strange thing happens. She becomes the vehicle that exposes their guilt, not her own. She humiliates them by revealing their impotence, and their shame is converted into her strength. In frustration, the patriarchs can only increase their punishments. They beat harder and harder, but she, who has not lifted a hand against them, who has used words and peaceful protest as her weapons, flips the hierarchy they so desperately want to protect by demonstrating her indomitable moral superiority over them. She does not give in. She speaks again. And the edifice they claim to have built on bedrock begins to sway. When those who hear her, look down at its foundation, they realize bedrock is swampland—a morass of vanity, greed, and hunger for power.

Thousands of girls and women, as well as boys and men, in Iran, have taken to the streets in resistance. They have been met with bloody retaliation from an entrenched but shuddering regime. It is impossible to know when the fissures become gaping holes and the building collapses, but when it does, you will remain a woman who did not give in. You are one extraordinary person, but we who believe in you and support the cause of universal human rights are many. That struggle does not end. It goes on.

In Humility, Rage, and Awe, —Siri Hustvedt, New York

Ahdaf Soueif

Salamat Narges Hanem,

Last month they sentenced you again; another 18 months of your life they want, after you finish the 16 years which follow on from the 11 which follow on … it becomes an absurdity. They clocked you when you were a student, some 30 years ago, and they’ve never taken their eyes off you since.

And what was it you did to earn all this attention? You campaigned, in Iran, for the basic rights of your fellow Iranians and their dignity. You spoke against the death penalty. You insisted that respect for human rights was part of a correctly practiced Islam. Most importantly, you would not stop. Speaking, writing, organizing, campaigning — you would not stop. This latest punishment is for standing up for the rights of the women inside Evin prison.

People like you really irritate the authorities. People who just won’t drop their bundle of human values and run, who cannot compromise on the sanctity of life, the integrity of the body; this person who speaks quietly, sometimes with passion, always with logic, who appeals to both reason and heart, to the best that is in us. And there’s a sharper viciousness against this person if they’re a woman or if they’re young; they’ve overstepped their station, they need to be taught a lesson.

Dear comrade, I write to you while my nephew, Alaa Abdel Fattah, is in prison in Egypt, and on hunger strike. He is 40 now, and he’s been in and out of prison for a decade; since the defeat of the revolution of 2011. Like you, he wrote a book. In it he writes: “I am in prison because the regime wants to make an example of us. So let us be an example, but of our own choosing.” You have chosen, and you have dictated your terms again and again. And when they exacted the price, you dictated more terms.

The cost has been heavy; the persistent malign intervention in your life, the pain of your loved ones, the decimation of your health, the separations. You are not Superwoman. You never pretended to be. You wrote: “I am a human being, a mother, a wife. How much more of this pain and suffering must I go through?” Well, that was 11 years ago, and you are still going through it. Worse: you have chosen for others which pain they should suffer. Your children, whom you sent away from you, to safety in France. Your children whom the authorities won’t allow to speak to you on the phone, forcing you to “affirm, through a hunger strike, my motherhood and my tenderness.”

There’s a photograph of you with your twins. You’re all dressed up and there’s a red velvet curtain behind you. They must be about five years old. Ali is in a green sweater, Kiana is more formal with a necklace and two pink flowers in her hair. Anyone who looks properly into your eyes will recognize — what shall I call it? A resigned determination? You know something bad is coming. You don’t know what it is. But you know you will face it, and face it down. Meanwhile an arm around each child holds them close.

I’ve gone back through your images, and back, to that round-faced bright-eyed young woman with the tumble of curly hair who registered at Imam Khomeini University in Qazvin to major in applied physics; the young woman who founded a student organization to “throw light on complex issues” and another to “climb the highest mountains in Iran.” Oh Narges, they create better metaphors than we ever could: “due to your political activities,” they ruled, you were forbidden to climb mountains! Well, look at the mountains you have climbed, my dear.

Alaa writes: “All that’s asked of us is that we fight for what’s right. We don’t have to be winning while we fight for what’s right, we don’t have to be strong while we fight for what’s right, we don’t have to be prepared while we fight for what’s right, or to have a good plan, or be well organized. All that’s asked of us is that we don’t stop fighting for what’s right”. But I write you this letter in the hope and belief that you will win in your struggle for “peace, tolerance for a plurality of views, and human rights” — and soon.

—Ahdaf Soueif, Cairo