Greeks today rarely discuss the civil war that raged for three years not long after the end of WWII, in which a predominantly communist uprising fought the Kingdom of Greece. 158,000 people were killed and a million became temporary refugees in their own country. A Greek novelist has captured the action.

Niki, a novel by

Nektaria Anastasiadou

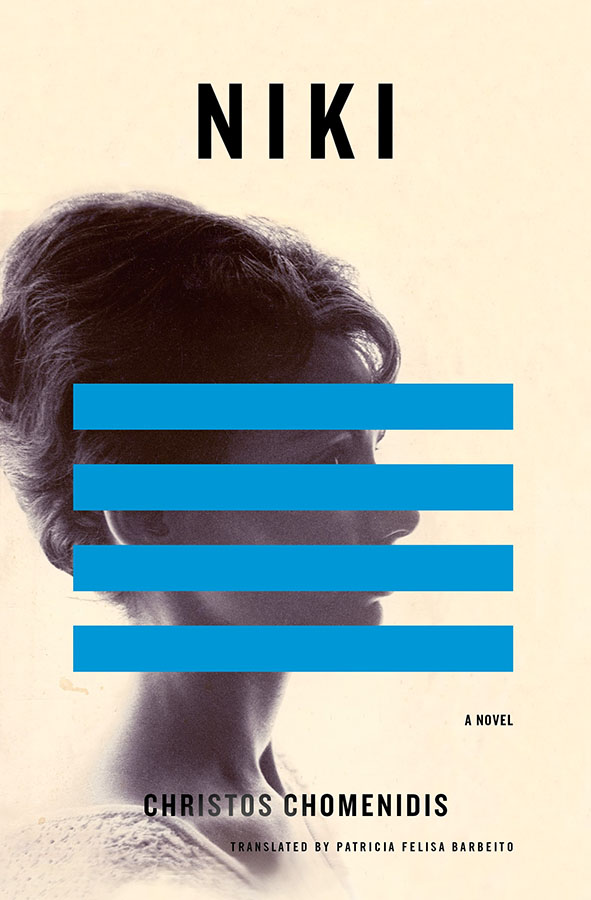

Telling tales, whether of one’s own experience or of the distant past, has been a Greek hobby since pre-Homeric times. While sipping coffee or ouzo, one can hear elderly Greeks talking of events that occurred decades or even centuries ago as if they had happened yesterday. The Revolution of 1821, the expulsion of Orthodox Christians from Asia Minor during the forced Greco-Turkish Population Exchange of 1922-1924, and the WWII Nazi occupation of Greece feature prominently in our casual repertoire. Conspicuously missing, however, is the more recent Greek Civil War of 1946-1949, an armed conflict between communist insurgents and the established government, during which Greeks committed unspeakable crimes against fellow Greeks. It is this gap of memory that Christos Chomenidis’s novel Niki, which won the Greek National Book Award and the Prix du Livre Européan, attempts to fill.

The story of fictional Niki Armaos, inspired by the author’s mother Niki Nefeloudi, begins after her death. Comfortably resting in the morgue while awaiting burial, Niki’s spirit narrates not only the first 20 years of her own life on earth, but also the histories of her grandparents and parents. The novel is an extended series of delicate, charming, and often humorous vignettes, beginning with the late 19th century elopement of Niki’s Peloponnesian maternal grandparents to a cave, as well as her maternal uncles’ induction into communism in the 1920s: “These days,” says Uncle Achilleas, “if you’re not a communist you’re either blind or a complete idiot.”

Leaving the Peloponnese behind, Niki’s spirit crosses the Aegean to recount her paternal family’s departure from Mudanya, Turkey, in 1922, as well as their brief and unfortunate stay in Constantinople, where her grandfather loses his entire fortune after being deceived by a deacon (and likely illegitimate son), something that could easily happen in Istanbul today. This, of course, is one of the author’s strongest skills: Chomenidis writes so vibrantly that Niki does not seem to belong to the past, but to contemporary life.

The novel’s narrator Niki Armaos is born in Athens in 1938 to fervent communist leaders Anna and Antonis Armaos. While her father is imprisoned in Corfu for political reasons, Niki passes her infancy with her exiled mother on various Cyclades islands, including Kimolos, where she is briefly kidnapped by a female donkey, “the possessor of what was clearly a strong maternal instinct,” which carries Niki unharmed in her muzzle to a manger.

At the outbreak of WWII, Niki is sent to live in Athens with her paternal grandmother, her collaborator uncles, and her plucky aunts, the sort who tell Niki in one breath to make the sign of the cross and pull up her socks. Reunited with her leftist parents at the end of the Nazi occupation, Niki’s adjustment to communist values is difficult, especially when her mother demands that she give eight of her nine dolls to destitute friends in a special ceremony: “The dolls were lined up like toy soldiers on the living-room table, and I, like a hooded informant at an Occupation blockade, had to point them out and name them one by one. I started bawling again.”

At the heart of the book — and perhaps its best writing — is the Battle of Athens, a series of clashes that took place from December 1944 to January 1945 between communist resistance groups and British and Greek government forces. In mid-December 1944, an unexploded grenade lands in the family’s yard. Niki’s terrified grandmother venerates the household icon of Saint Barbara, hangs her baptismal cross around her neck, and, “with the precision of a surgeon — or rather of a monk carrying a holy relic,” transports the grenade to a vacant lot far from the house. A few days later, Niki’s father Antonis, knowing full well that the communist forces are going to lose the Battle of Athens, nevertheless proceeds to commit an insane act of self-sacrifice for the benefit of the resistance organization ELAS: he dismantles and then blows up his mother’s house in order to obtain materials for use in the building of road blocks, as well as firewood “to warm the bones of little children.” This show of loyalty, however, leaves his own child homeless. Chomenidis could not have written a more poignant tale to illustrate the lunacy of civil war:

I glimpsed on the kitchen door the lines my grandmother had drawn in pencil when she measured my height at each birthday. Soon they would be lapped at and devoured by flames, and nothing would remain to attest to the fact that once I had been knee-high to a grasshopper and fit almost entirely in Aunt Fani’s hatbox […] Lined up on the opposite sidewalk, we look like we are posing for a photograph. It’s raining melting snow. Bursts of machine-gun fire and the thunder of cannon reverberate in the distance, as they do throughout the day […] My father lights the fuse. The explosion is like an earthquake; it convulses the entire neighborhood, raising a huge cloud of smoke and dust. When the cloud dissipates, our house is no more.

In 1948, the family learns that Antonis Armaos’s arrest and probable execution are imminent. Ten-year-old Niki decides to follow her parents into hiding within their own city, serving as their supplier of food and information for seven years. In 1955, finally free to live a normal life, Niki begins working as a waitress in a high-end café owned by her capitalist uncle. She falls in love with another waiter, which is where I will leave the story so as not to spoil the ending.

Fiction narrated by the dead is based on the fascinating premise that death is just as much of a beginning as an ending. Chomenidis’s Niki begins like Machado de Assis’s The Posthumous Memoirs of Bràs Cuba, but it claims its own space within the genre, for Niki remembers not only her own story, but also scenes that occurred before she was born or that she did not witness, including her parents’ intimacy. It is a risky point of view, both first-person and omniscient. The reader might question how Niki can know what happened in her parents’ bedroom or on her father’s solo trip to Alexandria, where he ran into his own illegitimate son; but, in the end, we on this side of life have no idea what we may learn on the other.

Having read the novel first in Greek, I was delighted with Patricia Felisa Barbeito’s elegant and artful translation, which lends an epic feel to Niki’s story. The only drawback of the English edition is the use of distracting footnotes. Gabriel García Márquez said that a novelist must attempt to hypnotize so that the reader thinks only of the story that is being told. When footnotes are added to fiction, they destroy the magic that we novelists try so hard to create; they wake us from the slumber of visions to which Puck refers in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Wouldn’t it be preferable to let a historical reference or two slide (or, even better, skillfully incorporate absolutely necessary information into the text itself) rather than wake readers from their dream? After all, a novel — even in translation — is still literature, not anthropology.