Boum & Berber’s compelling account of the “undesirables’” wartime migrations and displacements characterizes the graphic novel as another form of “memorial,” that attempts to name and bear witness to history through a high-impact, visual medium.

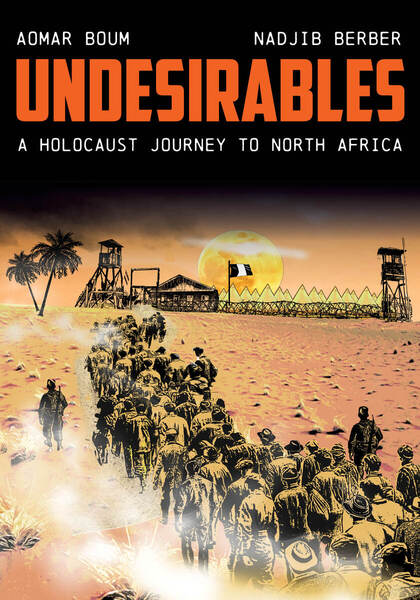

Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa, a graphic novel by Aomar Boum & Najib Berber

Stanford University Press

ISBN 9781503632912

Katie Logan

Early in Aomar Boum and Nadjib Berber’s new graphic novel, Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa, a German journalist named Hans walks through the streets of Paris with an Algerian compatriot. The two men, both Jewish, reflect on Hitler’s rapid rise in Germany and debate next steps: should Jews in France begin making plans to flee or to stay and fight? As their debate unfolds, illustrator Berber situates the two in front of the Arc de Triomphe, the Parisian monument with a notoriously complex pathway to construction. The monument’s intended commemorative purpose shifted as power exchanged hands in 19th century France; each leader pointed to a different lineage of military prowess to justify their claims to authority. Even after an 1836 inauguration, names of key figures and battles continued to be added to the monument’s base, an ongoing attempt to construct and consolidate French national identity.

For Berber, incorporating the Arc is not merely a matter of visual interest or a way of reinforcing the characters’ presence in Paris. Instead, the inclusion gestures toward one of the central preoccupations of this new account: what we commemorate lasts. The stories we tell about our nations, communities, and histories are always constructed, always framed. No matter how many revisions the Arc de Triomphe underwent, names and events are missing from its base. In each missing name are missed possibilities: a lost chance to understand French history from a new perspective or to draw a connection between seemingly unrelated events.

Undesirables is an effort to reintroduce perspectives and connections that tend to be muted in histories of Nazi Germany’s atrocities and those of collaborators like the Vichy government. The collaboration between Boum, a historical anthropologist, and the late comics artist Berber takes its title from a policy advanced by Vichy France. “On September 27, 1940,” Boum writes, “Vichy declared foreign Jews and Spanish Republicans ‘undesirables’ and a burden on the French economy. Vichy called for their internment.”

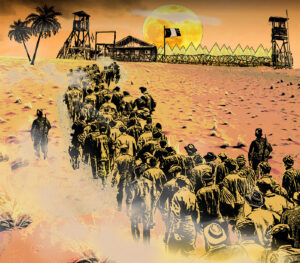

As Undesirables carefully documents, much of this internment occurred in the more than 70 labor, disciplinary, and internment camps across North and West Africa. To be undesirable, then, was to be doubly expelled, both from Europe and from what would become the more prevalent narratives about World War II’s scope of impact.

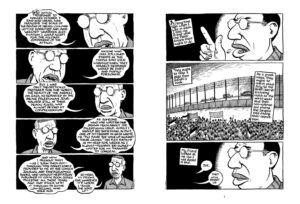

Boum and Berber’s compelling account of the “undesirables’” wartime migrations and displacements places greater emphasis on the way European anti-Semitism intersected with ongoing colonial projects in North Africa. The project’s afterword characterizes the graphic novel as another form of “memorial,” that, like the Arc de Triomphe, attempts to name and bear witness to history through a high-impact, visual medium: “Graphic memoirs are retroactive ethnographic accounts where witnessing takes place through seeing guided by the archive. The use of images as a form of Holocaust writing, starting with Maus, is a call to look, and therefore remember, through witnessing history.”

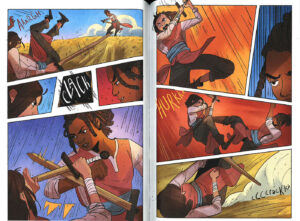

The witnessing that Boum describes here is not just about discovering new, singular events or histories. Instead, the text’s visual and narrative elements confront readers with the unexpected, complex solidarities that emerged when populations with a diverse range of religious and ethnic identities came into contact under occupation. Boum and Berber’s rationale for form echoes that of Jenny White, who herself turned to graphic narrative as a container for her scholarly research. She explains that in her own experience with oral history in Turkey, “the graphic approach allows the inclusion of a fuller spectrum of the variables that provide a context for factionalism (including gender and social class) and brings these variables into conversation with each other.”

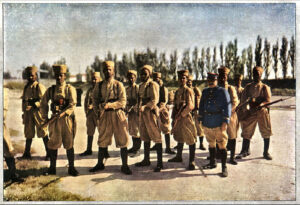

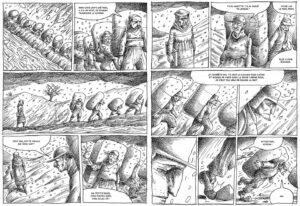

Boum and Berber embody the variables of their own research in their narrative’s protagonist, Hans Frank. The child of a Spanish, Sephardic mother and a German Ashkenazi father who served during World War I, Hans is a journalist who reaches adulthood just as the Nazi party begins commandeering German political discourse, along with the air waves. As Hitler comes to power and begins detaining journalists, Hans leaves Berlin for Paris and then Spain, where he reports on the Spanish Civil War. Eventually, he joins the French Foreign Legion to fight Hitler and Mussolini. When France surrenders, foreign nationals are expelled from the legion. Hans flees to Algeria and intends to head to relatively safer Morocco next. Before he can make the journey, he is arrested and sent to a Vichy labor camp in the Sahara. There, he encounters other Jewish detainees as well as Algerian Muslims, Senegalese marksmen conscripted into the French army, and Spanish Republicans.

Hans, Boum explains in the afterword, is a fictional character, a “composite” of accounts that the creators located in French, Israeli, Moroccan, and American archives. The invented nature of the character designates the text as fiction, but that classification does a disservice to the research that informs Hans’ trajectory. Reading Hans as a character, one might wish for more development of his internal landscape, particularly upon his arrest or when he loses family members. As a vehicle for synthesizing and bringing narrative shape to extensive archival research, however, Hans is enormously effective. His role as a journalist and legionnaire allows the text to move across national borders and to orbit around historical figures including Einstein, International League against Antisemitism president Bernard Lecache, and Morocco’s young Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Youssef. And his complex family dynamics revitalize the reader’s understanding of Weimar Germany, a place where many — including German Jews — failed to recognize the threat Hitler demonstrated until it was too late. Hans watches politics destroy his parents’ marriage, exposing fault lines and highlighting diversity within European Jewish communities.

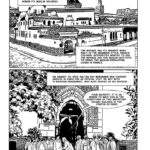

Hans’ own understanding of the diversity of Jewish experience, as well as Judasim’s encounters with other religious traditions, expands as he travels. Along with the Arc de Triomphe, Berber’s other major architectural rendering is Paris’ Grand Mosque, which was completed in 1926 and aimed to both memorialize Muslim soldiers who fought for France during WWI and to reinforce the colonial relationships between France and North Africa. We take a small detour from Hans’ perspective to sit in on a discussion between Moroccan Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Youssef and Si Kaddour Benghabrit, the mosque’s director. The conversation allows readers to see the way faith and political leaders were thinking about complex affinities and building solidarities across group identity, in an effort to prepare for Germany’s military intrusions.

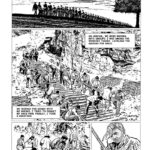

The dialogue between the Sultan and Benghabrit (whose efforts to protect French Jews during the Vichy regime were made into a film in 2010) demonstrates a central aim of this project: teasing out the linkages between a range of 20th century fights for liberation and against oppression, antisemitism, and colonialism. Multiple characters note that France’s decision to grant Algerian Jews but not Muslims French citizenship has created dangerous fault lines in Algeria (this move ultimately makes the Jewish population more susceptible to violence like deportation to Nazi concentration camps). As colonial occupiers work to divide Jewish and Muslim populations, figures like Morocco’s Sultan Mohammed point to solidarity as a key element of resistance. Undesirables also illustrates the way that Vichy France’s detention of foreign Jews, in concert with Nazi efforts, maintains colonial power in Africa. Hans and his fellow detainees are conscripted to work on rail lines and highways, construction projects traditionally undertaken by occupying forces to “socially engineer” conquered lands, preventing insurgency attempts and connecting control centers.

The graphic form makes it possible for readers to visualize these power dynamics in new ways. Berber, who sadly passed away shortly after Undesirables’ publication, worked previously in Algeria as a political cartoonist. His sophisticated awareness of the way visual media can reinforce or challenge political power is readily apparent throughout the work. During street scenes in Berlin, characters pass by — and largely ignore — Nazi propaganda posters. These posters don’t require commentary; their insidiousness comes from their omnipresence, the way in which they’re normalized across the landscape. It’s the reader’s responsibility to observe and reflect on these connections. As White writes, “I believe that graphic books work because they invite the reader to incorporate their own experiences in the mental process of ‘figuring it out’. . . . The suspicion lingers that graphics dumb down content and ideas, but I found that the opposite is true, that analyses can become more sophisticated and effective if readers are given permission to participate.”

In Boum and Berber’s case, the responsibility that readers bear is one that requires us to look closely, to sit with the faces of those who experience disenfranchisement and torture, and to reckon with assumptions and biases about received narrative. We participate in the intellectual and ethical work of learning how to draw connections, understanding Nazism’s rise to power by accounting for the way it was supported and sustained by pre-existing colonial networks, for example.

What readers will take from Undesirables is not only an invaluable history lesson but also a new method of thought. Boum and Berber challenge us to reflect on the Arc de Triomphe as historical subjects and civic beings — what names, events, and connections do we need to add to tell a fuller story of who we are and how we got here?