A psycho-social-virtual memoir of Palestine of both emotional and geographic proportions.

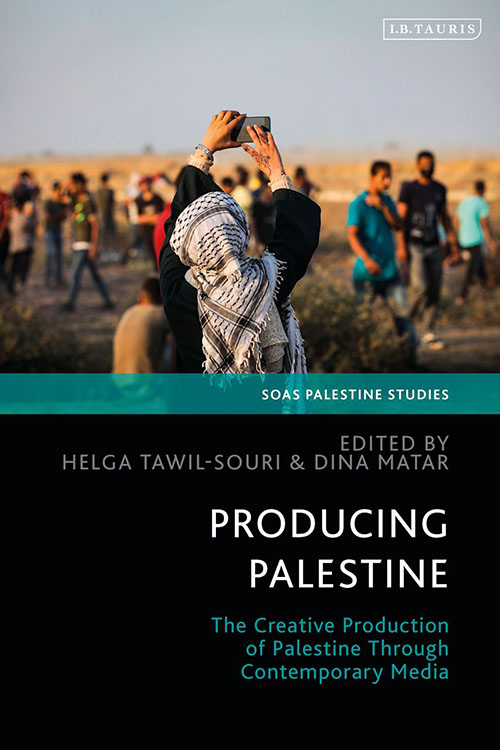

Producing Palestine: The Creative Production of Palestine through Contemporary Media by Helga Tawil-Souri & Dina Matar

Bloomsbury Publishing 2024

ISBN 9780755654277

Envisioning a continuous past, present, and future verge on the impossible. Yet East Jerusalem artist Larissa Sansour insists, “It is hard to talk about the Palestinian trauma without addressing several tenses, and histories. The Palestinian psyche seems to be planted in the catastrophic events of 1948 and is tied to a constant projection of the future, yet the present is in a constant limbo.”

The sixteen essays in Producing Palestine: The Creative Production of Palestine through Contemporary Media are caught in Sansour’s future-past-present. The anthology, edited by Helga Tawil-Souri and Dina Matar, explores new media and technologies. It also interrogates maps, databases, apps, snap chats, mobile phone film footage, graffiti, posters, kitsch, games, stickers, and selfies that conjure, produce, and delineate Palestine. In their entirety, the essays provide a psycho-social-virtual memoir of Palestine of both geographic and emotional proportions. They also give voice to the many thousands whose lives have been either lost to genocide or blighted by relentless occupation.

Producing Palestine arrives at a historic juncture. Palestinians and many others wonder, as the book’s co-editor Dina Matar said: “What use is (more) images or words when Palestinians are (still) being killed, vilified, and silenced.” Matar made those remarks as she presented the anthology to the SOAS conference “Archiving Gaza in the Present” in December.

Multitudinal returns

People have been struck by social media footage of Gazans walking north days after the ceasefire took hold, while the rest of the world couldn’t help but wonder how those who had lost loved ones and their homes felt about the landscape of sheer devastation around them. “They were singing,” said Harvard Divinity School’s Hilary Rantisi almost in awe and disbelief. “They are an example to us all.” For Palestinians the reality of return invigorates and renews against all odds.

Return casts a long shadow over Tawil-Souri and Matar’s Producing Palestine anthology. Contributor Rayya El Zein, in her “A Place Called Return,” admits she comes from a family that normally doesn’t speak about going back to Palestine. The writer, researcher, and second generation Palestinian was raised in the diaspora. She still tries to visit her family’s properties that were once called “home” in Yaffa. Her strange, bittersweet travelogue is filled with barred entryways, near misses as she approaches family properties, and the kindness of strangers who remember (and sometimes feign forgetfulness of) the odd landmark as El Zein looks for places from an old family photograph.

She writes of attempts to “locate … return in the everyday practices of what might otherwise be recognized as tourism. More specifically, I am wondering what the role of micro returns like mine … can play in a collective ‘protocol of recognition’” — the writer borrows a phrase from Rebecca Stein in Itineraries in Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and the Political Lives of Tourism — “in the current chapter of Palestinian imagining a horizon called Palestine.”

The game, Countless Palestinian Futures (CPF), developed by Danah Abdulla and Sarona Abuaker and played in London’s Mosaic Rooms, in 2021, encourages thinking on identifying issues raised by return.

In their essay for the book, “Imagining Return, Countless Palestinian Futures” designer/educator Abdulla and the poet Abuaker explain that they “wanted to develop a tool that did not frame Palestinians as victims but rather as people who take ownership over their own narratives.” (Listen to audio clip below.)

CPF is based on The Open Work by Italian philosopher Umberto Eco and his theories of audience participation. The game aims to “stimulate the imagination by helping people to develop tangible outcomes and ideas around Palestinian futures — to empower players to not limit themselves by the political imagination of others … In other words, who and what are we — as Palestinians after the struggle.”

Players are presented with question cards from the game’s different categories: Culture and Media; Economy; Geography; Governance and Policy; Infrastructure; and People and Society. Some of the questions are theoretical — “Would liberation include a Palestinian ruling class?” Others are practical: “How would the ruins of deserted villages be revived sustainably for the influx of those returning?”

On the Internet, the many possibilities of return abound. In “Virtual Returns: Rehearsing and Remediating Return in Palestinian Video Practices,” Kareem Estafan begins with Zochrot’s iNakba. The app, he explains, from an Israel project meaning memories (female plural) recalls the towns and villages that were largely emptied in 1948, “maps the hundreds of Palestinian villages destroyed to create Israel, incorporating user-generated images and histories on an interactive map of present-day Israel.” He goes onto Palestine Open Maps, which he describes as “digitally overlays maps of Palestine from the 1870s, 1940s, 1950s, and the present to create open-source, searchable versions with which users can interact.” Another project is the interactive documentary, Jerusalem, We Are Here (2016), directed by Dorit Naaman. These are, in the words of another contributor to the book new media curator Dale Hudson, “virtual transportations for Palestinians, unable to travel due to Israeli restrictions.” However, Estafan, a professor of film studies at Cambridge University, also acknowledges that Palestinians have a long history of return without virtual aids.

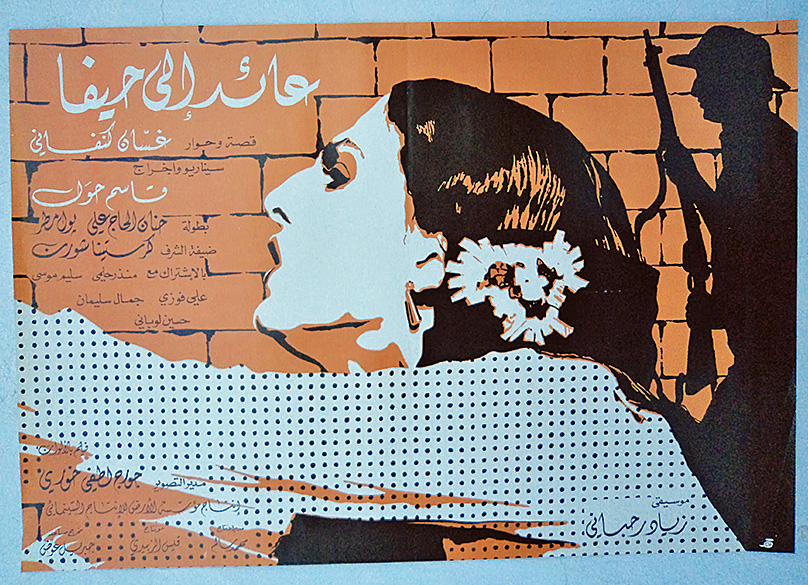

They “rehearse” return as in Ghassan Kanafani’s 1969 novella A’id ’ila Hayfa (Returning to Haifa), and “practice” defiant return as in the Great March of Return, the mass protests on the Gaza/Israel border, from 2018–2019 that was brutally suppressed by Israel. Estafan writes: return is “a structure continually imagined and performed by Palestinians.”

One of the anthology’s fascinating, and indeed more unusual, permutations of return is outlined in Aamer Iraheem’s essay, “Reincarnated: Common Sense and the Poetics of Elsewhere.” The anthropologist tells the story of 17-year-old Druze Nazih Abu Zeid in Majdal Shams in the occupied Golan Heights, who spied on the Israelis for the Syrians. On December 27, 1976, he was suddenly killed in an explosion as he crossed a minefield. The morning after Abu Zeid’s death, a baby was born to a Druze family nearly 80 km/50 miles away in the Galilean village of Hurfeish. The five-year-old Mazen Halaba would tell his family of a reoccurring memory he had of a big explosion. The Druze believe in taqammus or reincarnation, and the families of these two boys eventually came to the understanding that their sons’ lives and deaths are interlinked.

On a trip with his family to the Golan, Halaba routinely corrects a cab driver when the driver attempts to trick the child and tell him inaccurate place names near or around Abu Zeid’s family home.

This is a unique perspective on “return.” However, for Iraheem, “narratives of reincarnation hold a radical potential for opening up political and geographical horizons as they necessarily encapsulate histories beyond the immediate context of the here and now.” It can, he states, transcend “colonial and post-colonial borders.”

Yet again Palestine transits timelines and exists simultaneously in the past, present, and a possible future.

Powerful symbolism

Just as return necessitates movement towards homeland, there are essential Palestinian symbols that have migrated and morphed in meaning in the wider world.

In their essay “Becoming Al-Mulatham/a: Fedayee Art, Abou Oubaida, Palestinian TikTok,” Nayrouz Abu Hatoum and Hadeel Assaili explore the masked resistance figure, whether male or female. His/her facial features are often obscured by a wrapped keffiyeh around their head. Across social media this image has become the ubiquitous face of resistance beyond the context of Israel or Hamas.

Then what happens when the face and the eyes are removed, and only the outlines of the headdress itself remain? The keffiyeh, with its historic origins in the fellahin or Palestinian peasant, has been reproduced in posters, historic documentary photographs, Hollywood epic films, political posters and theatre. In brilliant visual criticism, “Marking Bodies: A Catalogue of Keffiyehs,” Sary Zananiri explains that he “reduces the keffiyeh to its constituent elements”; and demonstrates … how these different version of this headdress “mark the Palestinian body in different ways even when it is wrapped around a non-Palestinian body.”

The historic or cultural moment, in which the keffiyeh is donned, provides all-important clues, especially when the examples come from movies. The one sported by T.E. Lawrence in the David Lean film Lawrence of Arabia (1962) could be understood as a combination of admiration or the puerile (colonialist) thrill of “going native.” For cultural critic Zananiri, it embodies “the ambiguities of British positions toward Arab nationalist aspirations.” Jesus’s keffiyeh in Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical epic The Ten Commandments (1956), the author writes, “underscores the benevolence of Christianity, and hence liberal democracy, within the Cold War context.” Or the keffiyeh from the film Haganah (1960) “re-genders orientalist ideas of deviance regarding the politics of veiling.” By 1994, another Hollywood keffiyeh worn by a terrorist “marks a sense of threat to liberalism.”

Nothing is without context, even institutions like museums that purport to be receptacles of the past are rarely without their biases. So what relationship does a museum have with time if it is an institution charting the course of a continuing conflict? In her essay “‘We’re Still Alive, so Remove Us from Memory’: Asynchronicity and the Museum in Resistance,” Palestinian museum director Lara Khaldi considers the Yasser Arafat Museum in Ramallah before she argues that “the museum of resistance is a museum engaged in struggle. Therefore, it is a museum outside of time.”

To be there, beyond time, she believes, is also to be beyond “the reaches or archive and surveillance. It is obvious whose surveillance to which she is alluding. The prime example of this comes from the “archive of resistance” in the form of the book Falsaft al Muwajahah Wara al Qudban [The Philosophy of Confrontation behind Bars].

As Khaldi writes, “This book was smuggled in fragments inside capsules by political prisoners and circulated inside and outside of Israeli prisons to educate Palestinians about how to confront political imprisonment.” Devoid of any kind of publishing information, including the author’s identity makes the book “out of reach … The act of no-naming blinds the colonizer’s eye/discourse,” according to Birzeit anthropologist Esmail Nashif from his book, Images of a Palestinian’s Death.

Those institutions or objects beyond time have a value of their own, in terms of the Palestinian resistance. Falsaft al Muwajahah Wara al Qudban could be considered one of the technés of Palestinian liberation that another of the book’s contributors, Stephen Sheehi identifies in his essay “Forging Revolutionary Objects.” The techné is the “art, skill, or craft; a technique, principle, or method” from which liberation is achieved. Many of the technés, as Sheehi writes, “rebuff the military violence of the settler state now known as Israel” with “sacrifices and commitments of the Palestinian resistance – al muqawimah al falastiniyah.”

He cites the spoon, the one with which six Palestinian prisoners dug their way out of one of the hastily built and impermeable gulag, Gilboa, hastily constructed for the thousands of Palestinians arrested during the Second Intifada (2000–2005). With this single implement the prisoners dug for nine months through six inches of concrete wall, metal plates in the floor, and 100 feet of dirt, and tunneled to freedom.

After a frenzied manhunt, the six escapees were of course caught. During their arraignment one of the prisoners Ayhan Kamamji, yelled out: “We see clearly the resistance’s promise (wa’ad muqawimah) … victory is coming despite the nose of the occupier.”

As Sheehi, an academic, writes, “Objects associate with one another to make meaning within a history of popular mobilization.” Other technés of liberation are the gliders of two PFLP fighters in 1987, a Tunisian and Syrian who had powered their gliders with lawn mower engines, flew into Israeli occupied Southern Lebanon and attacked an Israeli base before the two fidai’s were killed.

The gliders, for Sheehi, recall the kites of Gaza, flying over Israeli defenses and guard towers and of the burning tires every Friday of the Great March of Return, which “blind[ed] IDF snipers” from targeting protestors. Gaza has one of the highest rates of amputated people because the IDF routinely shoots people in the legs.

Despite the powerful symbolism of these objects and their historic importance, he acknowledges that, “the revolutionary movement, politically, has largely been marginalized in the Palestinian polity.” Yet, despite this, “the popular culture, and psychological, social and cultural identification it has forged remains at the bedrock of Palestinian national identity.”

The cooking of the Palestinian celebrity chef Fadi Kattan, Palestinian poster art, graffitied wall murals of iconic figures such as Ahed Tamimi, and Palestinian queerness in Mashrou’ Leila song “Cavalry” are important topics that merit their own dedicated essays in the book. Despite the populism of the figures and cultural production at times the academic nature of the writing adds yet another layer of meaning to unpick.

The book’s last essay, “Terra ex Machina” by Dr. Hagit Keysar and Ariel Caine, is about one of Israel’s little known but enormously powerful barriers. An invisible wall, it surrounds Haram al-Sharif and the Temple Mount and 3 km/1.9 miles in diameter and with an almost ten km/6.2 mile periphery. This “geofence” is “a cylindrical digital barrier from the ground and up into the skies, set to prevent drone flight into or take-offs within the area.” However, unlike other forms of intense forms of surveillance that crisscross Jerusalem, which is controlled by the Israelis, the geofence is maintained and operated by the Chinese drone manufacturer DJI. Palestinian oppression is meat and bones for the international military industrial complex.

Keysar and Caine used 10,000 images taken from their own drone that oftentimes crashed into or was restricted from entering the geofence. However, the drone’s GPS were systems hacked at times the ban around the geofence was circumvented. These images were then combined with “do-it-yourself aerial photographs” taken from cameras attached to kites and balloons launched by residents, activists, and researchers. All of these were then fed through photogrammetry software, which the authors characterize as “the science of computing spatial and three-dimensional measurement of an object or a scene from sets of two-dimensional perspectival photographs recording it from multiple viewpoints.” The resultant composite of images provides the first, detailed — in part — illustrations of the geofence over Haram Al Sharif and Temple Mount. Perhaps the underpinning lesson of this essay: if it’s technological, with time and patience it can always be hacked.

The real field of conflict

In the epilogue to this remarkable anthology, Tawil-Souri and Matar recall Edward Said when they write, “The production of Palestine is not a field of detached, marginal, or virtual expression but a real field of conflict” (emphasis mine). As the Trump administration attempts to close down criticism of Israel in universities and public institutions, activism and cultural production remain the first line of defense.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)