One must ask whether “visualizations” of the unspeakable in the current context of Israel's war on Gaza have managed to render the viewer numb and disengaged, for what does it mean when we are shown daily evidence of atrocities and war crimes, and yet Israel's greatest defender, the nation providing the bombs and cover for its commission of war crimes, denies that war crimes are taking place?

In his book Images malgré tout (2004) the French Jewish art historian Georges Didi-Huberman took upon himself the analysis of four remarkable though hardly decipherable black and white photographs. These “images despite everything,” as Didi-Huberman described them, had been taken by prisoners of the Auschwitz concentration camp at the risk of their lives. For an uninformed viewer, they depict little else besides some trees, a few naked people and a fire burning (for incinerating bodies in fact). Yet, in his discussion of these images Didi-Huberman sought to qualify the opinion of other writers and intellectuals who argued that the horrific murders committed in the Nazi concentration camps were cases of the unspeakable, the unimaginable per se. For him, in contrast, the four images represented recognizable “traces,” or signs, of resistance.

The opposite point of view was deployed by Claude Lanzmann, the director of Shoah (1985). In his over nine-hour long documentary, the filmmaker deliberately refrained from showing the rare historical visual documentation of the camps, relying instead on the heartbreaking narrative accounts of eyewitnesses in combination with contemporary images of the camps’ remnants and the railways leading to them. This admittedly strong audiovisual strategy of representing the “unimaginable” or unspeakable relies on an extreme reduction of the visual, i.e. a minimum of images and a maximum of sonic evidence.

The same strategy has been occasionally re-adopted and recycled in theory and practice, just to name a very recent British fiction film, The Zone of Interest (2023). While the action of the entire film unfolds in the home of the then-Auschwitz commander Rudolf Höss, directly adjoining the walls of the camp, the terror of industrialized extermination seeps in periodically via remote sound effects, thus leaving death and suffering entirely to the viewers’ (un-)imagination.

It goes without saying that during the last decades the horrors of the Nazi genocide have neither remained totally unimaginable nor visually undocumented, given the immense number of films of all formats produced on the topic, ranging from Alain Resnais’ film essay Night and Fog (Nuit et brouillard, 1956), packed with visual evidence, up to Steven Spielberg’s box office hit, Schindler’s List (1993), to mention only two of the most canonical. Hence, by means of the audiovisual, the Holocaust has been rendered aesthetic, narratively dramatized and mainstreamed internationally. In Germany, this has certainly helped to raise awareness, at least among the younger generations including myself who were born after the war, yet the basic dilemma between cruelty that exceeds any form of possible expression, and the attempt to make it visually tangible and herewith risk profanity has not been resolved.

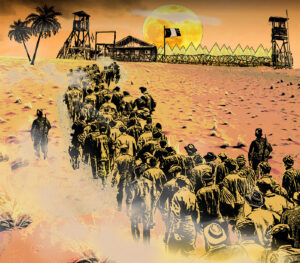

It is ever more urgent to ask if these “visualizations” of the “unspeakable” have indeed managed to dissect the complex nature of so-called antisemitism, or to call this child by its real name, of racism and xenophobia? Did they really help to elucidate the multifaceted mechanisms of social exclusion in Germany and elsewhere and pave the way for their dissolution? To put it differently: Were they able to exemplify the widespread modern productions of the “homo sacer” or “bare life,” to use Giorgio Agamben’s term; that is, a life that is pushed outside the common legal system and hence declared outlawed and erasable? For this latter process has not been confined to Auschwitz but, in the case of Germany, had started already in Namibia in the early 20th century, with the incarceration and extermination of the Herero and Nama, a fact that had been repressed for many decades.

Since the conquest of the Americas, genocides have been reported from almost every corner of the world, and more often than not, linked to the capitalist extraction of resources, forced labor and violent exclusive nation-formation. In addition, some of the most democratically labeled political systems have been involved in the unlawful production of “bare life,” such as the United States when it used Guantánamo Bay, a no-man’s land for human ostracization, combining ideological and religious labeling with a complete deprivation of civil rights, not unlike what is being practiced in Gaza and in the West Bank on the Palestinians.

“Shame on us,” exclaimed Noura Erakat, a US-based Palestinian scholar, lawyer and activist during the online Palestine Congress Tribunal on April 15, 2024. In the aftermath of the Palestine Congress in Berlin, which was raided and shut down by the German federal police on April 14 under the erroneous pretext of demagogy, she made a short but concise statement on the nature of the counter-attacks on Gaza. The fact that governments in the Global North had only protested loudly after the killing of seven international aid workers, while “30,000 Palestinian victims” had not been enough for them to express words of criticism against Israel was described by Erakat as racism. For her it was evident from the very first week of the war on Gaza that the Israeli backlash after October 7 was going to become a genocide. She asked how many more images of dead bodies and destruction the world needed to see until we would be ready to intervene.

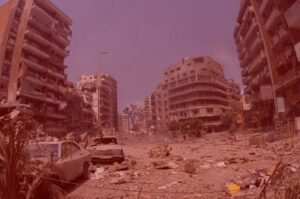

In a similar vein, Palestinian activist Omar Barghouti described the events in Gaza as “the world’s first livestreamed genocide.” What we see in this case indeed is no longer a “trace” that reveals signs of resistance. What’s coming out of Gaza today is an overwhelming amount of visual evidence. Gaza’s reporters and photographers have provided a surplus of audiovisual documentation of bombardments, massacres, captures and starvation. What has been locally recorded, gets copied, televised and shared online on a global scale. Yet, this fact has not led the warmongers to show mercy nor the spectators abroad to stand up in larger numbers against the cruelty of ruling elites in Germany, France, UK and the US. Their governments have equipped Israel — and are still supplying it — with military technology ostensibly meant to “defend” against Hamas’s armed resistance, but is actually attacking an estimated two million civilians who are trapped and starving between the sea and three almost impermeable borders.

Amidst all this havoc, the mass-mediated Speakable and Imaginable have reached another unprecedented level. Particularly on the social media platform TikTok, where Israeli soldiers operating in Gaza have made innumerable posts intensifying the general trend in Israel of “images that reframe disproportionate violence as proof of victory.” Many of these posts remind one of war trophies, pairing a thoroughly cynical playfulness with blatant cruelty, at least according to my reading.

For example, when a soldier tosses a match to his rear pretending to cause a huge detonation in the background, the (terrible) comic effect is stressed by the interplay between fakery and veracity as well as the successful temporal orchestration of the soldier’s hand movement and the real blast it supposedly causes. The bomb’s actual damaging or maybe even deadly effect on the location and its people is left to our imagination, intentionally implied, yet also ridiculed by the trivial effortless hand movement.

Examples of this sort of “humor” abound: in one instance the camera pans from an IDF member comfortably seated in an armchair just to reveal the shattered walls of a once nicely furnished Palestinian home; in yet another video, a soldier introduces an “open” university while walking us from an intact detail of a beautiful Andalusian arch to the crumbling walls of what was once one of Gaza’s 13 universities — all of which have been destroyed or rendered inoperable now.

The arbitrary vandalization of schools, the looting of goods and personal belongings from shops and homes in these images is so obvious they were submitted as evidence of war crimes in South Africa’s lawsuit against Israel at the International Court of Justice. Some have additionally attracted attention because of their misogynist content, such as the now-iconic photograph of a big red bra attached to a tank with smirking solders on top or the footage of soldiers playing with female lingerie, all of which went viral. Some images even alluded to rape, with soldiers posing with undressed mannequins while grabbing their naked breasts or dismembering large Barbie dolls. In fact, these documented sexist and supremacist fantasies don’t leave much room for the imagination as they make the fate of captured women and men in wars overtly palpable and add just another layer to factual cases of sexual violence against Palestinians.

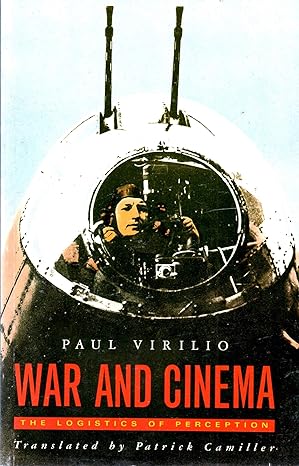

Yet what strikes me more deeply as a film scholar is the skillful application of cinematic vocabulary that ranges from composition, framing and camera movement, to staging and the use of faked “special effects” as mentioned above. In them I find that the convergence of perception and destruction in the parallel technologies of warfare and cinema contested in 1984 by French philosopher Paul Virilio in his War and Cinema (Guerre et cinéma) has reached an unprecedented level of perfection. His arguments of the parallel and intertwined development of cinema and warfare technology traceable from the view finders of machine guns and air bombers are certainly eye-opening. Since then, technology has rapidly developed to encompass flying drones whose bird’s eye perspective has not only become a must in every contemporary movie but also serves to cover both ends in the military realm: surveillance and targeted destruction alike.

Virilio convincingly explained how direct vision in battle and one-to-one combat has been exchanged with remote surveillance, and how we have familiarized military “ways of seeing” — as obvious as the expression “to shoot a movie” — and allowed them to permeate our culture: “Warsaw, Beirut, Belfast … the streets themselves have become a permanent film set for army cameras or the tourist reporters of global civil war,” he stated forty years ago. If he lived today, he would have to add Gaza to his list.

This is a bleak and sobering account indeed for those who may still have wanted to believe in the basically enlightening power of the image. Yet, this does not mean that there is no trace of resistance. While sifting through Netflix recently I came across an old short film from Gaza. One decade ago, Condom Lead (2013) had not only premiered at Cannes but also established the unconventional film career of its makers, the twin brothers from Gaza, Arab and Tarzan Nasser. Though they were born in 1988, one year after the last movie theatres had been closed in Gaza, they were able, against all odds to develop an exuberant cinéphilia that is detectable in all their works, and especially noticeable in their last feature, Gaza, Mon Amour (2020).

What struck me when watching Condom Lead was on the one hand its topicality, and on the other the surprising extent to which it insists on the war on Gaza as something in the realm of the Unspeakable. For the entirety of the film, we remain in the enclosure of a family home, observing the daily and nightly routines of a young sensual couple and their thwarted attempts to exchange intimacies while caring for their restless baby. With time we realize that the crying of the baby resonates with a second layer in the sound track, never seen but only heard, that of continuous shelling. Here again, we have a work that has decided to entrust the Unimaginable to the sound instead of the picture. This is why Condom Lead for me has turned into a film “despite everything,” in the sense meant by Didi-Huberman and mentioned at the outset of this article. That is, it is a film equipped with “traces,” or signs, of resistance. Or in other words, it is a conscious act of making tangible a horror that has been displaced and deeply internalized.

And yet I must finally admit that this audiovisual strategy of displacing the depiction of cruel inhumanity from image to sound is no more than a reminder of the current abhorrent state of the way our media handles such atrocities. At best it serves as a small stumbling block to the senses, like the ones we find on Berlin’s pavements consecrated to the memory of individual Jewish victims of Fascism. And yet as technology progresses exponentially, these filmic attempts to go back to a representation of the Unspeakable by absenting the image seem to have been reduced to a helpless gesture vis à vis the omnipresence of mass-mediated graphic, or “speaking,” imagery. For — and herein lies the real horror — in an attempt at self-defense our overwhelmed senses have begun to shut down, leaving us in a state of numbness, and condemning both image and sound to muteness.

Another moving and evocative rumination among this 12-essay collection! Many thanks/much appreciation to Ms. Shafik!

“The fact that governments in the Global North had only protested loudly after the killing of seven international aid workers, while “30,000 Palestinian victims” had not been enough for them to express words of criticism against Israel was described by Erakat as racism.” I’ve loved Dr. Noura Erakat’s passion and humanity since (it seems to me) she was a teenager! I can’t forget her taking on — and eviscerating — the execrable Colonial Zionist Prof. (sic) Alan Dershowitz in a memorable debate circa 2008….