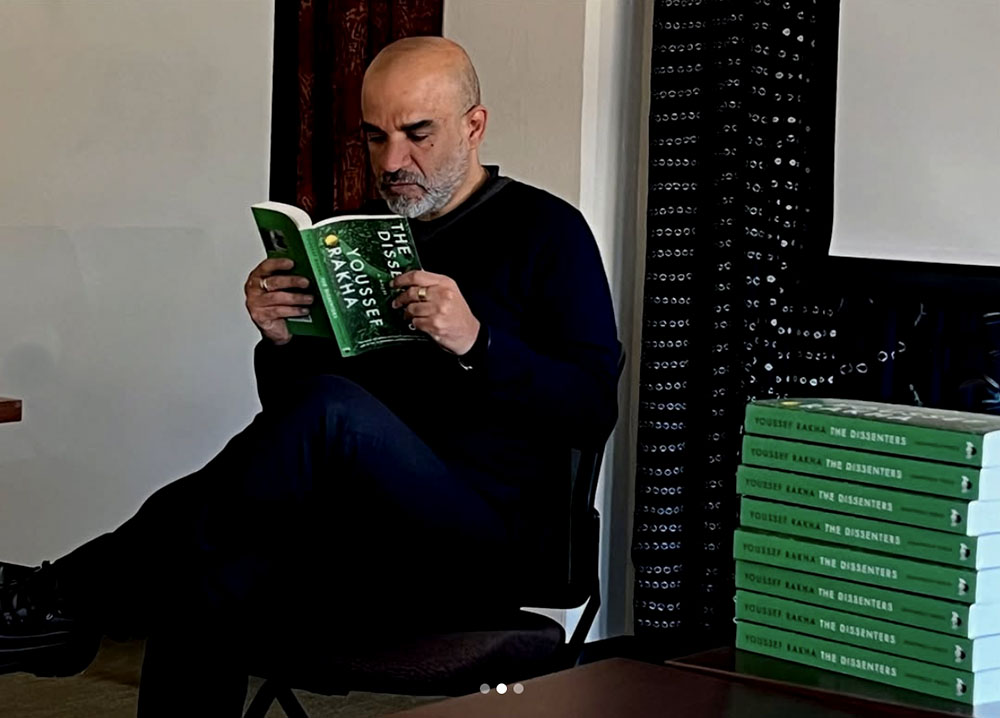

The Egyptian author of an epistolary novel — his first in English — meditates on whether his work will join the canon of world literature. Reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement last month, called a "powerful, shimmering and clever novel," The Dissenters is already on its way to winning over western readers.

There was a time when I believed that what I published in Arabic, translated, could be published in English to a similar response from critics and readers, and that the literary merit of my work was all that would be at stake. I believed my work had merit, and I thought it could grant me access to the space they called World Literature, where my writing could be in conversation with that of figures I admired. My naiveté was threefold.

As an Arab writer — that was the message — I don’t exist until my subject matter overlaps with an event deemed newsworthy. Then, providing I take the same position as the Western mainstream, I might be given some space. Otherwise, it’s as hopeless and humiliating as trying to move to a Western country on an Egyptian passport.

First, even in Arabic, I didn’t have a big enough readership to make publishing me commercially viable. It’s true no Arab or WL writer I respected wrote bestsellers — few sold in any numbers without western industry backing: awards, promotions, coverage — but what I didn’t know was that the reality of publishing in English requires at least some hope of financial profit. Like hundreds of other Arab writers, all I aspired to was critical acclaim and translation. That didn’t stop publishers from enthusiastically accepting my work — along with that of many others — as some of them continue to do today. I have no idea what’s in it for them except potential prestige. Since they never pay advances and seldom produce credible royalty figures, I suppose there is also the guarantee that what money comes in will be theirs.

Still, through the aughts in Egypt, the pulp series of genre novels — Man of the Impossible, Paranormal, etc. — were the only fiction that sold well; and they belonged less with literature as I understood it than with other things that did sell: graphic titles on religion and sex catering to pious and prurient impulses outside the purview of art. In fact it never occurred to me that sales could be a deal-breaker in richer, more open societies, where many more books were published and many more people read. So I remained blissfully unaware of the first major hurdle on my way to broader visibility.

I believed that if I wrote well enough I, a Cairo-based Egyptian working in Arabic, would eventually be admitted into the WL hall of fame. This delusion took a long time to dispel because, the more I despaired of making an impact in an Arab public sphere held hostage by religion, social authoritarianism, and political corruption, the more my ambition depended on looking out to further horizons. But it was willful blindness. Since 1901 there have been at least as many Arab as, for example, French authors whose life’s work merits a Nobel Prize in literature. Only Naguib Mahfouz got one — at the age of 77 — and he was a staid, conservative figure who modelled his work on 19th century European literature and took all the right, pro-American positions on Middle East politics since the Cold War.

If this was a typical example of how WL dealt with Arabic literature, which it was — considering, too, that I was whimsical and subversive and set out to defy and find alternatives to European narrative models — then I didn’t have much chance of being recognized outside the Arab world at all. But, judging by the handful of Arab writers who did get the treatment I felt I deserved in English, none of that mattered anyway. Only current news-linked political commentary, in effect neoliberal propaganda — sometimes veiled in literary sophistication, sometimes not — had any chance with the Anglophone publishing industry.

When in 2013-14 a relatively mainstream publisher took up Robin Moger’s translation of my second novel, The Crocodiles, this was not — as I eventually realized — because it was a Bolañoesque reflection on the life of Nineties poets in Cairo doubling as a history of Egypt from 1997 to 2012, but because it included an account of the January Revolution of 2011, which had been big news across the world; it was an account that happened to be compatible with the Western — neoliberal — response to the revolution.

The novel’s noir sequel, Paulo, uses an amalgam of the detective and horror genres — Jim Thompson-like, as I later discovered — to tackle the dark side of the same event. It complicates the received view of the Arab Spring as an innocent push for greater rights and freedoms, portraying activists as deranged spies and stressing the disastrous consequences of an Islamist takeover of power. Paulo is a compelling read, if I say so myself, and it was beautifully translated by the same Robin Moger just as soon as it appeared in Arabic — at a somewhat later date, I should add, when Egypt was no longer in the headlines. It has not been published to this day.

As an Arab writer — that was the message — I don’t exist until my subject matter overlaps with an event deemed newsworthy. Then, providing I take the same position as the Western mainstream, I might be given some space. Otherwise, it’s as hopeless and humiliating as trying to move to a Western country on an Egyptian passport.

By the time Paulo came out in Arabic, the reality of my prospects in English was dawning on me at last, but it was becoming more and more difficult to stay part of the local literary scene as well. The revolution had either turned into or turned out to be a ruse to let the Muslim Brotherhood monopolize power — the Islamist free for all that overtook society as a result was an absolute nightmare as far as I was concerned — and I was cancelled for pointing out that the protesters and the Brotherhood-coopted left continued to facilitate and enable this process even after it became clear that concessions to theocracy and civil strife were all the “ongoing revolution” could amount to in practice.

Activists had upstaged writers and artists on the culture scene, there was far less nuance and complexity in the discourse, but the character assassinations and holier-than-thou attitudes did not translate to better ethics, more rigor in information exchange, or a greater diversity of standpoints. Especially not in publishing: By the mid-teens, Egyptian publishers had begun to implement the commercial strictures of late capitalism for the first time, rejecting celebrated, well regarded authors because their manuscripts did not look lucrative, and putting out all kinds of “revolutionary” rubbish by social media influencers in pursuit of profit.

It was at this point that I turned to English, less out of the desire to try myself out on a different and bigger readership — the idea of a Great Egyptian Novel had seduced me since my teens — than to get past the intense, debilitating alienation overtaking me.

By now I had faced the fact that the WL had never stood for anything other than Western Literature (with Occasional Token Representation). But I didn’t realize until much later that, by drawing on my ability to write in English, I was also trying to circumvent the second hurdle on my path to visibility outside the Arab world.

Now that my English debut has — finally, miraculously — appeared, with a high-profile US publisher that truly respects and supports me, followed by a UK edition with a similarly committed UK press, I don’t feel like the OTR in WL. I feel like myself addressing a potentially worldwide readership against incredible odds. Because selling my English manuscript had proved to be a third hurdle:

Many of the agents and editors who rejected the book had very kind things to say about it, and the reason almost all of them gave was that it wasn’t about anything their target markets might be interested in. One editor said he didn’t see the point of publishing a book like this outside of Egypt. It didn’t seem to matter that it was written in English precisely so it could fly out to the rest of the world, with America as its inevitable waystation. Evidently he couldn’t imagine a piece of Egypt ever traveling in that direction. Restrictions on my freedom of movement as an Egyptian citizen were being applied just as reflexively to my work’s freedom of movement as a writer from Egypt.

All that’s over now, alhamdulillah. It remains to be seen how widely an English novel by an Egyptian can be embraced, which is ultimately not my business. Meanwhile I get to tour the United States to promote it: my first time ever across the Atlantic, weirdly timed for the height of winter and the start of the second Trump administration.

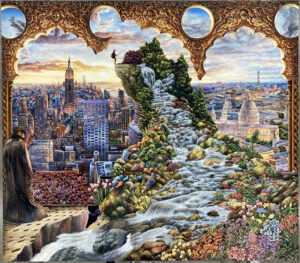

New York isn’t like any of the many cities I’ve been in Europe or the Arab world — nor in South or Southeast Asia — but the minute I set foot there it feels uncannily like home. Had I stayed on in the UK after I graduated from university, I conjecture, sooner or later I would have ended up here.

My Manhattan book event is so well and feelingly attended I leave the venue sputtering exhilaration, convinced I have at least as much of a community here as I do in Cairo. Past midnight, accompanied by a kindred New Yorker I’ve somehow found in the sound and fury of the event’s dénouement, I walk down Canal Street to the river in the cold. The exhilaration is condensing into a deep satisfaction when I have the disquieting sense that the person I am at this moment might not be me after all.

Back in England, in 1998, the question of whether I should stay on or return to Cairo was quickly resolved — far easier to be in Cairo: more affordable with no legal complications, so many more employment opportunities, and my parents’ unconditional support. But none of that mattered as much as how marginal and irrelevant three years in England had left me feeling. I didn’t want to endure what I saw as the stunted emotional range and the subtle contempt of a Western population that hadn’t reciprocated my enchantment. And yet by then I’d assimilated well enough to stay on more or less effortlessly if I had to…

As I look across the water to Brooklyn’s myriad sparkling lights, now, I’m thinking I probably wouldn’t have written in Arabic at all if I had stayed; and if I wrote in English and my writing found a readership, where else would that bring me?

Suddenly it is as though, in an alternate timeline, I stayed on in UK, eventually emigrated to the States and settled in New York. No wonder this feels like home: for at least twenty of the nearly thirty years that have elapsed since my graduation, that’s what it has been. And for a moment as I stand there laughing with my companion, like Zhuangzi dreaming he was a butterfly, I truly am not sure which of us I am, the real Youssef or that British-American Youssef that wasn’t.

Perhaps all that literary achievement amounts to is a renewed sense of self? I know then I have passed the fourth gate.

Very interesting, thank you!!

Youssef Rakha sounds like a great writer! I hope I can get his “Dissenters” book soon here! I am Italian, a scholar of Sanskrit and no fan of Modi nor of the Indian BJP party…keep up the good work.