India Hixon Radfar

A Dove In Free Flight, Selected Poems of Faraj Bayrakdar

Edited & introduced by Ammiel Alcalay and Shareah Taleghani

Upset Press (October 2021)

The truth is that poetry is the antithesis of prison, just as life is the opposite of death […] The moment of writing is the moment of true freedom, and poetry is the vastest space of freedom […] Poetry is democratic with its writer and reader […]Poetry allowed me to control my prison, rather than my prison controlling me. —Faraj Bayrakdar

Faraj Bayrakdar is a Syrian poet who spent years of his life in Assad père’s prisons, before he obtained asylum in Sweden in 2005. This rare and beautiful collection of Bayrakdar’s poems, available in English for the first time, was made possible by a group of committed writers and translators known as the New York Translation Collective, which includes Ammiel Alcalay, Sinan Antoon, Rebecca Johnson, Elias Khoury, Tsolin Nalbantian, Jeffrey Sacks, and Shareah Taleghani. The book features an interview with journalist and documentarian Muhammad Ali al-Atassi (translated from the Arabic by Taleghani), and an essay, “Portrait of a Poet,” by Elias Khoury, in which Khoury asserts, “the prison takes on the mirror image of writing.”

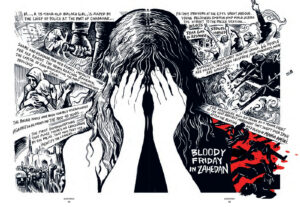

Khoury further informs the reader that, “The poet wrote his poems with ink made from tea and onion peels using a thin wooden stick in place of a pen. From prison to prison and torture to torture, he takes us on his voyage to experience the connection between the body and the soul.”

“The truth is that poetry is the antithesis of prison,” Bayrakdar declared in his interview with al-Attasi. I kept turning this phrase over and over in my mind as I slowly turned the pages of this book. I thanked the fates of good fortune that I have been a poet living in freedom, which I now take less for granted.

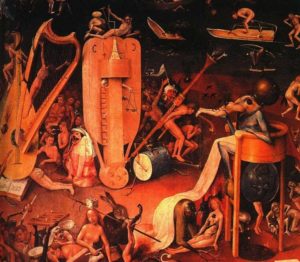

“The freedom within us is more powerful than the prisons we are in,” Bayrakdar declares. If we could remember this astonishing truth, how much more we would be able to do for the welfare of humanity. Poets, writers and artists are here to remind us of this inner freedom, and when one can do that from within a prison cell for as many years as Faraj did, we naturally want to listen, however grief-bound the writing is.

What I found from reading Faraj Bayrakdar’s A Dove in Free Flight was very different from what I expected to find. He shows us that when the body is imprisoned, it is easier to free the mind.

When Alexander Solzhenitsyn was freed from the gulag, he left Russia for America, and in Vermont, in the stone basement of his house, he built a room in which to write that had the exact dimensions of his old prison cell. J.D. Salinger created a dark space with high windows that resembled a WWII bunker below his home in rural New Hampshire. He wrote there alone. No one else was allowed to enter. The artist Ai Weiwei filmed himself living in a space the exact size of his prison cell in Beijing, China, his goal being to retell what one day of living in that cell was like. Ai Weiwei still uses the shape and dimensions of his cell in many of his art pieces.

But it is really Arabic poetry that has taken the concept of imprisonment and made it a trope in poetry.

We all know that actual imprisonment is different than the concept of imprisonment. Faraj lived out over thirteen years of a fifteen-year sentence, withstanding torture, but his poems show that he still understood the freedom of the mind. He wasn’t given paper or pen, like the poet Anna Akhmatova in her cell in Tashkent, Russia. But they both found ways of getting their poems to the outside. It wasn’t until Faraj’s release in 2000 that he knew all his poems had made it safely out and had been collected in one place. Once his release was negotiated, he made this statement: “After having written much for death, I would like now to write for her sister, life.”

Faraj continues to write in Sweden.

What exactly is the experience of a prisoner? As much as we want to see them freed, we also have a desire to understand. Elias Khoury and his students and colleagues at NYU in 2002 made an effort to understand by translating Faraj’s prison poems into English. After many years, the collection was edited by Khoury’s colleague, Ammiel Alcalay, and former student Shareah Taleghani, and made available to all in 2021 by Upset Press. And what do we find in these pages? We often find exactly what our hearts were hoping to find; that even in the darkness and near death of his prison cell, Faraj is writing about freedom. “For my prison cell is my body / and the ode incidental freedom.”

“Earth isn’t a prison cell, but you are solitary and bereft,” Faraj says to a howling wolf, having already disassociated himself from the wolf’s misery. “Since my cell is a body I claim / and a freedom that claims me,” “I face you as a way out.”

He writes a lot about the women in his life: his wife, his daughter and his mother, often combining them with images of birds and butterflies and other things of beauty. Sometimes he writes about the wounds he is receiving: “Forgetfulness wounds,” “the moment is wounded,” “every wound a manifesto.” Only once does he devote a whole poem to his interrogator/torturer:

Portrait

The curse said to him be

so he was

his eyes two dirty copper buttons

his nose an exclamation point

drawn viciously

his mouth the shape of a silencer

and his tongue in the barrel of the gun.

On his shoulders peacocks rest

bloated with defeats

he owes debts that would

bankrupt even the blood banks —

He tends to us

with a blind heart

and guards us

with barbed wire

his intentions are booby-traps

and his smile heralds a massacre

his wisdom is death

and his justice hell…

Forgive me… I’ll stop.

I’m about to faint —

Maybe he’s not exactly like that —

Yet,

he is…

Saydnaya February 1993

But there is one metaphor that comes back repeatedly, and that is of the bird on wing:

“…does captivity test the

wings a bird uses to

swoop down freely,

finding no meaning that isn’t

far from their twin meanings?”

It is a rhetorical question, but after reading Faraj’s book, I think we can say yes. Once Faraj discovers this, “The universe celebrated by adding two extra skies.” And we are left imagining, puzzling, glad that Faraj’s devotion to freedom in these poems has become his reality.

Wonderful work and may shareah teleghani, who edited the collection rest in peace. We are still devistated by the news of her death.

Wonderful work and may shareah teleghani, who edited the collection rest in peace. We are still devistated by the news of her death.