The Lebanese duo’s new theatre-performance, Four Walls and a Roof, uses trial testimony, humor, and iconic Eisler-Bertolt Brecht songs to explore today’s rising tide of the right

Malu Halasa

Originally from Lebanon now living in Berlin, Rabih Mroué and Lina Majdalanie have been watching anti-democratic currents rise in Europe and the wider world. Their latest theatre-performance play Four Walls and A Roof turns to the testimony of Bertolt Brecht to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1947. The HUAC hearings, which interrogated Hollywood directors, screenwriters and composers about their ties to domestic subversion — including Brecht’s long-term collaborator, composer Hanns Eisler — were a precursor to the virulent anti-communist McCarthy hearings that took place seven years later, in 1954.

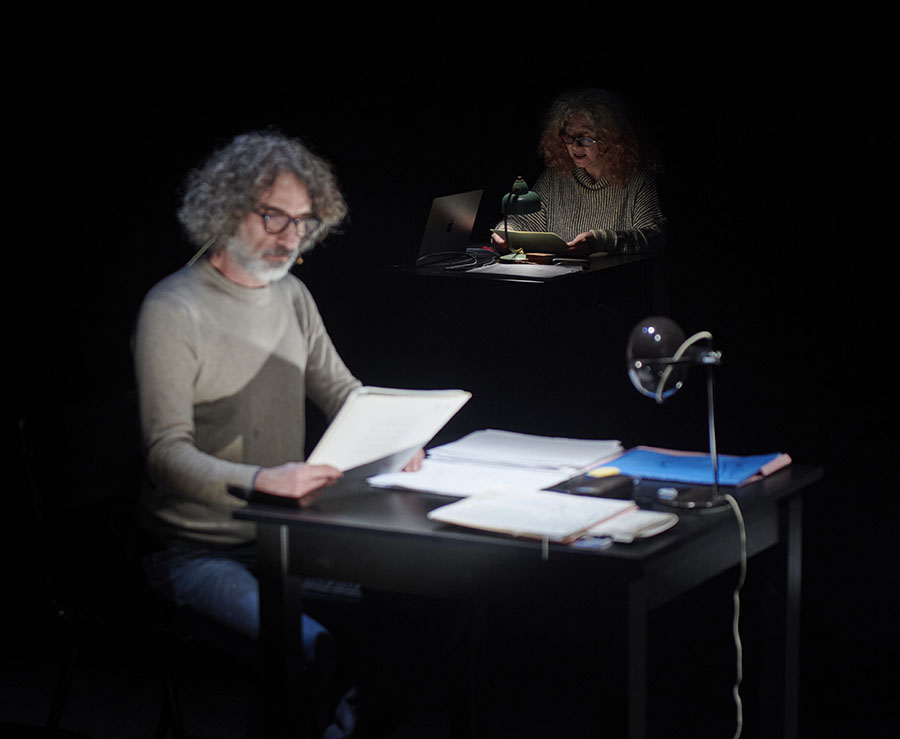

Majdalanie and Mroué are known for pushing the structures of theatre as well as a critical posture on current events, whether in Looking for a Missing Employee (2003) about the Lebanese Civil War or Pixilated Revolution (2012), about mobile phones and new technology during the war in Syria. Their plays, which they have described as “theatre-lectures” or “theatre-performances,” challenge the limitations of storytelling, political and otherwise. In Four Walls and a Roof, which premiered in Paris and currently on tour in Europe, Mroué and Majdalanie explore censorship, fascism, and the suppression of free speech, themes that inevitably draw parallels with the events of today.

Speaking from backstage at the Kampnagel Hamburg, the day after their production’s debut in Germany, the two long-term theatrical collaborators are articulate, impassioned citizens of the world. They discuss, among other issues, the importance of naming that which is considered politically or socially uncomfortable and the role of humor in providing distance for audiences to reflect. Four Walls and a Roof also includes Brecht’s statement that HUAC would not allow him to read at the hearing, alongside the iconic songs by Brecht and Eisler. In our interview, Mroué and Majdalanie also emphasize the broader implications of their artistic practice, and address the rise of fascism globally and the need for cultural resistance.

Malu Halasa: When Angela Davis was in London recently, she described antisemitism in its current inception as a political tool in US politics, as the new McCarthyism. I read about your new lecture-performance Four Walls and a Roof and the October 30, 1947 testimony of Bertolt Brecht to the House Un-American Affairs Committee at the same time I watched the video of the arrest of Rümeysa Öztürk at Tufts University by ICE (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents). To me, it seemed like the perfect storm. The past resounded in the present. Can you describe your new theatre-performance and the motivations behind it?

Rabih Mroué: The starting point was the Bertolt Brecht trial in 1947 in Washington, DC. For many, many years we are interested in the relationship between trials and theatre. Like theatre, a trial gives the opportunity for different points of view, even if they are at war and against each other. The difference is that theatre, contrary to the court, at the end, doesn’t give a verdict. It stays open, and the judgment is always left to the audience to decide individually their opinion.

So in this sense, like we were thinking about Palestine in Germany, specifically, what’s going on here, especially after the 7th of October 2023, the silencing and censoring. We were also thinking about our situation: how we can approach this artistically and in a theatre piece. This is how we came back to the trial of Bertolt Brecht, and we thought that it’s a good starting point to think about our situation today.

TMR: Brecht, the playwright and poet of the Weimar Republic, operated at a time of increasing, terrible fascism. Are you feeling these currents in Germany today, or are you also thinking of this in the wider world?

Lina Majdalanie: We cannot compare the situation now with the Nazi situation. And this, we are clear about it in the performance. We cannot make a parallel very easily between the two situations. It would be a big theoretical error because, as we say in the performance, history doesn’t repeat itself, but there are some patterns in histories.

TMR: I read that history doesn’t repeat itself, but some rhythms are the same.

LM: Mark Twain said that. We are thinking larger than Germany or the West. This kind of censorship and witch hunts, we are used to it in our in our countries where we come from, and where many people have had to leave their countries in urgency or “Okay, I had enough. I’m looking for more democracy and freedom.” And they find themselves now in occidental democratic countries where these signs are growing and growing and growing. Luckily, we have not and, I hope, will not arrive to the point like 1930s and the Nazis. But nevertheless, it is important, necessary, and urgent, to say: “Hey, stop!” We don’t have to [get to] the point where we are like the Nazis to say, “Stop.” We have to start at the beginning because it is really dangerous.

TMR: I’ve always thought that Lebanese, Syrians, Palestinians, because of the levels of violence or conflict or the situations in those countries, have given the people there a kind of experience that those living in in the US, or those living [where I am] in London, don’t really know. It’s because of this experience — whether we’re talking specifically about growing up during the Lebanese Civil War, or we’re talking about the war in Syria, or what’s going on in Sudan — people who have what I call a kind of “accelerated understanding” of how a society can turn on a dime, what can happen. Actually, if there’s anyone who can discuss with us, or [be able] to show us what we can’t see, what’s in front of us, is perhaps Middle Eastern cultural practitioners. I don’t know if you see this as your mission.

LM: Essentially, I would never dare to say it myself in a loud voice. But indeed, this is what we have the impression of when I discuss it a little bit with Rabih and friends. It is that: “Hey, we know how this progresses. We know how it will evaluate. We know to watch [or where] it could reach.” Finally, it is as if our countries are a laboratory, and we are afraid that the same thing could happen here in Europe, in democratic countries.

RM: Although, Lina and I have lived in Berlin for many years, nevertheless we still feel that we don’t know much how to deal with the laws, the official institutions, the censorship, etc., like we know how to deal with it when we were in our country. Here there are nuances and details that we don’t know and don’t control. [We don’t] know how to play with the system like [when] we were in Beirut. In Lebanon, the censorship is very obscene, it’s present, and doesn’t hide itself, as in Europe.

TMR: I would have thought that dealing with such outright censorship in Lebanon, you’re also very good at allegory —

RM: —I don’t like [allegory] actually, don’t use it at all. This is what was proposed to us in Lebanon. They told us, “Why you don’t use allegories, metaphors, symbolism, like the Russians do?”

No, no, no, we want to name things. It’s important to say, is this the issue? To put the finger on the problem without, for example, metaphorizing, abstracting, hinting. No, no, it’s important. They fear that we name things.

TMR: Then let’s return to Brecht’s October 30, 1947 testimony in front of the House Un-America Activities Committee. It doesn’t seem like he’s really naming things. When one of his poems is read to him in English he says, that’s not what I wrote; I wrote in German. He was very good at somehow deflecting the idea that he has written revolutionary poems and plays with revolutionary sentiments, and still he is able to show that the context in which these works were written was very different. It’s interesting that the committee members said, “Oh, that’s a different country. We’re not interested in Germany.” They refused to see parallels.

LM: Yes, but he was in the USA like us in Germany, where we don’t know exactly all the tricks here. Probably Brecht in the USA also didn’t know exactly what were his rights. If you compare with his other colleagues, who were also summoned to trial with him, like [the American director and screenwriter Herbert] Biberman and many, many others, they were so strongly fighting with the committee. Brecht was in a more fragile and precarious situation because he was a foreigner in the USA. He didn’t know all the little tricks and details. In Lebanon, we can also name very clearly, and we know what to expect, and we know how to confront. In Germany, we would be less able to, because we don’t know very well every detail in the system, the laws, the society. We don’t know the language. We are precarious and fragile here.

RM: With our theatre performance we were interested in the questions and the quality of the questions and the repetition of the questions, and how, like the court and the judge and all the apparatus of the court, they were not in any way interested in Becht’s answers. They want just to know “yes” or “no.”

TMR: When I read Brecht’s testimony transcript for the first time, it made me wonder about the interrogations pro-Palestinian university activists had been undergoing after their arrests. That’s what also frightened me. Of course, I admired Brecht’s ability to somehow avoid what could have happened to him. But it was the repetition, the accusations against him — there’s not much room to maneuver. [The committee members] do want a yes or a no. That’s scary. You’re using the actual transcript of the Brecht testimony. But also, you are also referring to the statement that the HUAC would not let him read.

RM: He was repeating during the first third of the of the trial, always insisting and repeating at the same time, “Would you allow me to read my statement? I would like to read my statement …” and then at the end, they are very direct with him: “We are not interested in your statement. We are not interested of having you read the statement.” So they throw it away.

We were imagining if they would have allowed him to read the statement in the court, what would have happened? We actually bring the statement [into the theatre performance], and we hear the voice of Bertolt Brecht reading it. Of course, this is our fantasy to make him speak what he wants to speak, because also all the others accused in the court, like the Americans from Hollywood, they have also statements that they not allowed to read. In the court, they were forbidden.

TMR: I’m also curious about Brecht’s unread statement, and where it comes from is problematic. It was reprinted in English in a book by Gordon Kahn Hollywood on Trial, and then it appears on an album Brecht before the UN American Activities Committee. But that is has been described as a “lightly edited version.” The original German didn’t come out until 1967. What were your sources?

LM: The text of the statement, first, we found it on the internet. Then Sandra [Noeth, responsible for Four Walls and a Roof’s dramaturgy] did research in Germany. She found the original German version. Then we readapted the English one to the German one.

TMR: Another aspect of Brecht’s testimony to the committee that I found disturbing was this idea of guilt by association. In this group of Hollywood actors, writers, screenwriters, musicians, if one was “revolutionary” i.e. a threat to public order, all of them were. And again, that made me think of the pro-Palestinian movement. You have someone that simply signs a letter at Tufts University, calling for divestment of Tufts from Israel. And then, this person is doxed, and everyone that person has been seen or filmed with, is guilty too. Did that idea of slamming a group come into your performance?

RM: To make it clear, we were not trying to associate what happened to Brecht and to the Hollywood artists, writers, directors, to what’s happening now to the pro-Palestinians and the Palestinians in the world. We were actually linking it to everything. It’s not only if you are pro-Palestinian; if you say anything against Trump, or criticize Trump, you are deported from America, or you are not allowed to enter the States. Also, like you can see the International Criminal Court in Den Haag. Now they are under the sanctions of the Americans because they [pronounced] a verdict against Netanyahu and his minister.

So [Four Walls and a Roof] can apply to everywhere, even in the Arab world. What concerns us is this idea of the shrinking of democracy, of freedom of speech, of expression of opinion of the people, and this dictatorship that is appearing everywhere in the world, not only in Europe, and just against the Palestinians. Of course, the Palestinian cause is now. It’s the ultimate absurdity. But it’s also with Trump — criticizing Trump now — is another absurdity. And of course, like we don’t talk about Putin, if you are in Russia. It’s the same thing if you are in Saudi Arabia. If you criticize the crown prince, the king, then you are also in jail, or, you’re deported, and so forth. The question is, how you can deal with all this?

TMR: What you’re saying is that your theatre performance has a much broader remit than just one issue or two issues, and this is what gives the piece its universality. I remember when I saw Missing Employee many years ago. I was so taken with the fact that the story about someone in Lebanon was so universal. And I thought then that this seemed to be the essence of theatre, that you can take a local story, it opens in front of you. I’m sitting at the ICA in London — and this story about Lebanon in all its absurdity, but also in its complexity, is something that I recognize and understand and empathize with and am shocked by. Four Walls and a Roof also has this broader remit?

LM: You asked for our motivations. Our motivation [is to show] the rise of fascism all over the world, the rise of the right wing all over the world, and how freedom of speech is being cut now. As Rabih said, it’s obvious with the Palestinian Israeli conflict, but it is reaching many other topics and layers and subjects. We didn’t narrow the performance to the actual political situation of Palestine and Israel. It starts from what is going on Earth today.

RM: I would like to add something related to your thoughts about Missing Employee and this [new] work. There’s something very important for us when we do artworks, when we do performances in theatre: we try not to be activists in the narrow sense of the word. We try to do a reflection, to put questions and ideas that we share with the audience, and we try to discuss so we don’t give conclusions that this is wrong, this is right. Of course, we don’t hide our political positions, for example, with Pixelated Revolution about Syria, we are against the Assad regime. But there are a lot of questions, a lot of ideas that are unfinished and gaps that have to be filled with the audience, together. Four Walls and a Roof is trying to give different ideas, questions, doubts, uncertainties, to share with the audience, in order to reflect together. So it’s not like that we have a conclusion like definitive answers, etc., without hiding our political position. It’s not like pretending that we are neutral, no not at all, but we do not want to convince the audience [of a particular] a point of view.

TMR: So you’re not trying to win an argument.

LM: Exactly, yes, not trying to win an argument.

RM: Coming back to the idea of the court trial in relation to theatre, and this is actually the core: how we can build a court in theatre where we give voices to each component, like the two sides or three sides against each other, without giving the conclusion. The verdict will be [left] open. It should be kept open, contrary to the work of the judge in court.

TMR: So it means you trust your audiences.

LM: It’s like [French New Wave director] Jacques Rozier says: you have to trust the intelligence of the audience. Exactly. We have to because our work is about deconstructing existing, very rigid discourse, and to deconstruct it by trying to see the internal contradictions [the audience doesn’t] want to see, and by bringing in other things that will trouble what they think is a completely well-constructed idea, ideology and discourse. But it’s not. And then, it collapses, collapses. We hope that we work on collapsing, making deconstruction.

TMR: What is the function of humor in Four Walls and a Roof?

RM: First of all, we don’t push this. It’s not like we have to be humorous in the piece. It comes naturally, because I’m a person who loves to make a lot of jokes; humor is part of my personality. But of course, we noticed that when you insert some humor in your very sensitive topics, it gives the audience the opportunity to stand away a little bit distance from the topic. It cools down what is hot, or sensitive.

TMR: To provide a breathing space?

RM: It’s the Brechtian method. It’s how to give the audience distance in order to think a little bit far from emotions.

LM: About humor, also any dictator or regime on the way to become oppressive and authoritarian — humor annoys them. If you are in a tragedy and the victim etc., they will be very happy, while humor could annoy them a lot.

TMR: Do songs also have a similar function?

RM: Songs are similar, but also they are another layer. In Four Walls and a Roof, we’re working with Henrik Kairies, a specialist in the music of Hanns Eisler, who collaborated a lot with Brecht. The theatre-performance is an opportunity to listen to the amazing music of Eisler, plus the lyrics and poems of Bertholt Brecht, which we chose very carefully so that they fit our topic.

LM: In the trial transcript the committee asks Brecht two times about the songs he did with Eisler.

TMR: In Brecht’s unread statement, he wrote, “Only a very few people were capable of seeing the connection between the reactionary restrictions in the field of culture and the ultimate assaults upon the physical life of a people itself, the efforts of the democratic, anti-militaristic forces of which those in the cultural field were, of course, only a modest part then proved to be weak altogether. Hitler took over.”

This is my final question: is culture stronger than totalitarianism? Can culture hold back the tide of fascism?

LM: Unfortunately, culture takes time. It’s not an immediate result. But culture by itself builds something. It’s not that you do a performance or a song, and people will be aware, but with time it makes sense.

RM: We have to do our work.

This interview with Rabih Mroué and Lina Majdalanie at Kampnagel Hamburg has been edited for length and clarity.