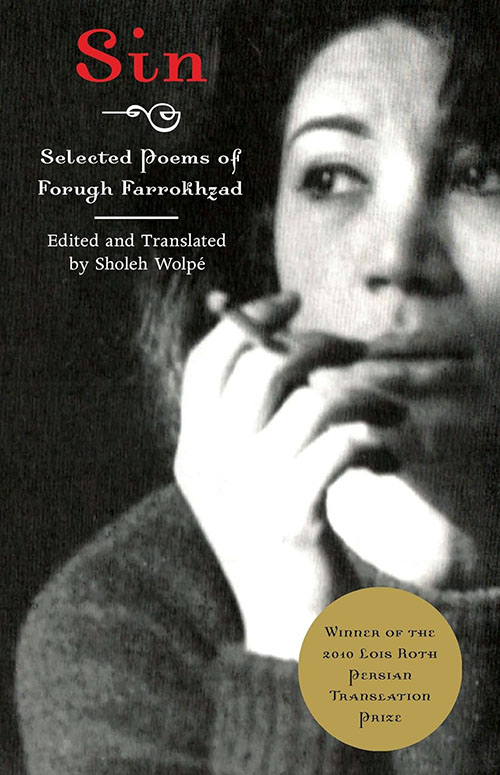

In which the writer remembers what it was like to lose her voice as a result of personal tragedy, and relates to the poetry of Iran's classic 20th century poet, Forugh Farrokhzad.

Life and art are a perpetual journey of searching, nurturing, and fine-tuning voice. Participation with life occurs through voice. To elevate one’s voice is a central responsibility of being human, because, according to poet Forugh Farrokhzad, ultimately it is only voice that endures. For Farrokhzad, expressing her voice through art was “a vital need, a need on the scale of eating and sleeping, something like breathing.” This compulsion, despite the immense challenges she faced living in Iran during the 1950s and 1960s, reflects her belief in the power of voice as both a creative necessity and an act of resistance.

Sholeh Wolpé, Farrokhzad’s translator, says her “poetry was the poetry of protest — protest through revelation — revelation of the taboo: the innermost world of women, their intimate secrets and desires, their sorrows, longings, aspirations and at times even their articulation through silence.” Farrokhzad’s poetry is known for its sensuality, boldness, exploration of female identity, and candid expressions of personal and political issues. Her poetry tackled taboo topics such as love, desire, and the struggles of women in Iran’s patriarchal society. Her lover, Ebrahim Golestan, the renowned Iranian filmmaker and intellectual, shared in an interview how much he admired Farrokhzad’s fearlessness in a society that continually castigated her. He believed the greatest influence on her work was Farrokhzad herself; her own experiences and desire for freedom and self-expression. As she wrote in a letter to him:

I want to reach the heart of the earth. My love lies in there, a place where seedlings turn green and roots meet one another and creation continues even in disintegration. I think it has always been this way — in birth and then in death. I think my body is a temporary form. I want to reach its essence. I want to hang my heart like a ripe fruit on every branch of every tree.

I first became interested in “voice” through encounters with silence: the absence of voices, those forgotten, deliberately excluded or erased. A couple of years ago, as I compiled an anthology of menstruation experiences, I noticed which voices were missing from the mainstream discourse, particularly those marginalized by politics, poverty, occupation, religion or social status. I saw more clearly which voices were privileged, ignored or shouted down. This led me to search out those voices which were muted either from fear, shame or lack of confidence, or oppressed by cultural norms. As I discovered them, I began to understand how integral voice is to identity, freedom, and agency. One instance was when I was interviewing homeless women outside a Sufi shrine in Multan, Pakistan. I realized they were reluctant to speak to me because we were being watched by a group of men whom they presumably feared. Equally, I noted how transmen were unwilling to speak about their menstruation experiences because they were afraid of being ostracized or losing their jobs. The more I researched, the better I understood how patriarchy, religion, and politics had created and propagated myths of shame around periods, and stigmatized them as a way to control womens’ bodies and choices. Over time, my reflection on voice prompted me to revisit Farrokhzad’s poetry. Her life and work offered comfort and a framework to understand my own struggles with bringing voices to the fore and silencing forces in my life.

Farrokhzad’s poetic journey spans from personal entrapment to profound liberation. Her evolution is reflected in her poems written a decade apart, “The Captive” (1955) and “Only Voice Remains” (1966), where the shift from the voice of a “captive bird” to a triumphant, defiant “voice” marks a transition from suffocation to freedom. The contrast between these two poems provides insight into Farrokhzad’s inner life — her journey from the oppressive confines of Iranian society to a renewed understanding of her own agency and spiritual liberation. In some ways, it helped me understand my own trajectory in appreciating the necessity of using one’s voice for resistance, lowering it for self-preservation, and rediscovering its resilience after a period in the tunnel of silence.

In “The Captive,” Farrokhzad presents a vivid portrayal of imprisonment, both personal and political.

The Captive

I want you, yet I know that never

can I embrace you to my heart’s content.

you are that clear and bright sky.

I, in this corner of the cage, am a captive bird.

From behind the cold and dark bars

directing toward you my rueful look of astonishment,

I am thinking that a hand might come

and I might suddenly spread my wings in your direction.

I am thinking that in a moment of neglect

I might fly from this silent prison,

laugh in the eyes of the man who is my jailer

and beside you begin life anew.

I am thinking these things, yet I know

that I can not, dare not leave this prison.

even if the jailer would wish it,

no breath or breeze remains for my flight.

From behind the bars, every bright morning

the look of a child smile in my face;

when I begin a song of joy,

his lips come toward me with a kiss.

O sky, if I want one day

to fly from this silent prison,

what shall I say to the weeping child’s eyes:

forget about me, for I am captive bird?

I am that candle which illumines a ruin

with the burning of her heart.

If I want to choose silent darkness,

I will bring a nest to ruin.

Here Farrokhzad uses imagery to create an atmosphere of isolation and tension where desires are irreconcilable with reality. The speaker in this poem likens herself to a “captive bird,” separated from the expansive sky, with a heart like a “candle which illumines ruins” and confined behind “cold and dark bars.” This stark image of imprisonment, of longing for flight but knowing its impossibility, mirrors Farrokhzad’s own struggles against the claustrophobia of her marriage and Iranian society. Yet, even within the cage, the speaker finds ways to imagine freedom, to dream of escape. In the poem Farrokhzad switches from addressing the reader, her lover, and herself. She yearns to “spread my wings in your direction,” visualizing a future beyond the prison possibly with her lover. However, she also recognizes the limitations imposed by her reality and her own lack of energy: “even if the jailer would wish it, no breath or breeze remains for my flight.” The yearning for independence is palpable, but overshadowed by the speaker’s own pessimism about her capability, “no breath or breeze remains,” alongside the stark realization that escape is out of the question. The poem ends on a note of resignation, with an acceptance that the probability of release is low and if she did, she would destroy “the nest.” The speaker is referring to the idea that she is bound by the expectations of patriarchal norms in Iranian society but also by her own inability to act, despite her intense longing for emancipation.

This feeling of entrapment resonated with me shortly after publishing Period Matters: Menstruation in South Asia (Pan Macmillan, 2022). As I sought to amplify the voices of homeless or incarcerated women, those working in factories, sweeping streets and forest dwellers, trans people, and women living in remote geographical areas, I began to appreciate how women’s bodies were inescapably political. Menstruation was a taboo subject, and through the poems, essays, art, stories and interviews presented in the book, I tried to show how the menstruation experience could be better understood through an intersectional lens. Aside from being a time of rest and healing, menstruation could also be a time of female solidarity and regeneration as practiced by the Kalash women in Northern Chitral, or one with immense creative and artistic potential. For instance, the book showcased menstrual art or menstrala. These included images of embroidery and needle work on underpants, visuals of murals in a village in India depicting menstruation in a positive light, and the cover of Period Matters which included a detail from a painting made with menstrual blood. The book also included a QR code to a dance where the dancer used a classical raga and gestural movements to reflect the lunar rhythms of her body during menstruation. However, the book was met with hostility by Islamic right-wing fundamentalists in Pakistan who have narrow ideas about women’s autonomy and rights, and keep them subjugated. The fundamentalists posted a video on YouTube circulating conspiracy theories about the anthology and linking it to anti-Islamic ideas such as those in Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, and asked for a fatwa on me. In the days that followed, I received death threats, was banned from attending literary and social events in Lahore, and warned not to enter Pakistan. I was forced to go into hiding, and close my social media accounts. During those months I was furious that my life was being controlled by unknown men with beards, but also quite frightened by the backlash. I reflected on the nature of silence and voice. Was I, too, becoming like the captive bird? Should I stop? Was my desire to speak out worth the immense personal cost? In that silence, I grappled with these questions, trying to navigate the tension between self-expression and self-preservation.

I returned to Farrokhzad’s “Only Voice Remains” — a poem written ten years after “The Captive” that marks a dramatic shift in her tone and perspective.

Only Voice Remains

Why should I stop, why?

Birds have gone to seek their blue way.

The horizon is horizontal,

movement vertical– a gushing geyser.

Bright stars spin as far as the eye can see.

The Earth repeats itself in space, air tunnels

become connecting canals and day changes

to an entity so vast it cannot be stuffed

into the narrow imaginations of the newspaper worms.

Why should I stop?

The path meanders among life’s tiny veins

and the climate of the moon’s womb will annihilate

the cancerous cells, and in the chemical aura of after-dawn

there will remain only voice—

voice seeping into time.

Why should I stop?

What is a swamp but a spawning ground

for corruption’s vermin?

Swelled corpses pen the morgue’s thoughts,

the cad hides his yellowness in the dark,

and the cockroach

… ah when the cockroach harangues,

why should I stop?

Printer’s lead letters line up in vain.

Lead letters in league cannot salvage petty thoughts.

My essence is of trees; breathing stale air depresses me.

A bird long dead counselled me to remember flight.

Fusion creates the greatest force—

fusion with the sun’s luminescent soul,

comprehension flooding with light.

Windmills eventually warp and rot.

Why should I stop?

I hold to my breasts sheaves of unripe wheat

and give them milk.

Voice, voice, only voice.

The water’s voice, its wish to flow,

the starlight’s voice pouring upon the earth’s female form,

the voice of the egg in the womb congealing into sense,

the clotting together of love’s minds.

Voice, voice, voice, only voice remains.

In a world of runts,

measurements orbit around zero.

Why must I stop?

The four elements alone rule me;

my heart’s charter cannot be drafted

by the provincial government of the blind.

What have I to do with the long feral howls

of the beasts’ genitals?

What have I to do with the slow progress

of a maggot through flesh?

It’s the flowers’ bloodstained history that has committed me to life,

the flowers’ bloodstained history, you hear?

(From: Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad, University of Arkansas Press)

Here Farrokhzad’s speaker declares that, although the body may be bound, the voice, spirit, and mind are ultimately free. The poem celebrates the power of consciousness and its ability to transcend temporal limitations. It opens with the powerful lines: “Why should I stop, why?” Unlike the speaker in “The Captive,” who is resigned to captivity, the voice in “Only Voice Remains” is defiant. The speaker is no longer asking permission or pleading for release, instead she asserts her right to exist, to speak, and to continue her journey, regardless of the forces that attempt to silence her. This confidence is evidenced by the eight questions directed at the forces which threaten to stifle her.

In “Only Voice Remains,” the insistence on the continuity of the speaker’s voice becomes a radical assertion of autonomy: “The four elements alone rule me; my heart’s charter cannot be drafted by the provincial government of the blind.” Farrokhzad imagines her identity as being directed by the elemental fertile and regenerating forces of nature, and scorns ideological structures that try to control her. The visceral fecundity of images of sound and movement such “The water’s voice, its wish to flow, the starlight’s voice pouring upon the earth’s female form, the voice of the egg in the womb congealing into sense,” emphasize the rebirthing and newly found enlightenment of the speaker. The resilient voice, as it “seeps into time,” moving beyond the ephemeral, is permanent and transcendent unlike the body which is liable to decay. Farrokhzad uses words and images of life and death to highlight this contrast: “breasts,” “milk,” and long feral howls of the beasts’ genitals’ suggest intense living and feeling, while “the slow progress of a maggot through flesh,” and ‘flowers’ bloodstained history,’ hint at the transience of flesh and blood. The effect is that the fragility and profundity of the natural world is emphasized as temporary, while its essence as eternal.

In contrast to “The Captive,” where the speaker’s longing for flight is subdued by her captivity, “Only Voice Remains” is a sensual and triumphant declaration that nothing can suppress the voice. Here Farrokhzad writes with a burgeoning political consciousness and addresses corruption and decay in Iranian society as suggested by her use of metaphors of “swamps” and “vermin,” and her critique of the state as a “provincial government of the blind.” Her mention of “newspaper worms” and “cancerous cells” are subtle references to the censorship of her poetry by the state which had banned it because it went against what could be expressed by a woman after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Despite this, the speaker declares that voice will persist, and “seep(s) into time.” The poem represents Farrokhzad’s defiance of oppression and her belief in the power of voice to resist, adapt, and resonate through “history.”

My reflections on Farrokhzad’s poem deepened my understanding of voice, not only as a tool for communication but also as an expression of autonomy, and resilience. In the face of external pressures, I realized that my own voice had become one of rebellion, much like the voices of the women I interviewed for my book. The women who spoke up, reminded me of Farrokhzad’s assertion that voice is a force that transcends physical boundaries. One of the most poignant stories I collected for my anthology was that of a young woman in Balochistan, who, despite receiving death threats for breaking the “balochmayar” or code of honor for speaking out against tribal rituals, conducted the first-ever menstrual health workshop for girls in her village. She encouraged them to think about menstruation as a natural experience, not clouded in myths of dirt and impurity. Similarly, I learnt how language around menstruation could also be embedded with ideas of weakness and ill health to keep women from becoming empowered. For instance, the Bengali words shorir kharap literally mean “unwell body” and is the phrase used for menstruation. These stories, along with the others I collected, hinted at the potential of a menstrual revolution to bring change, ignited by voices which refused to let silence reign.

Farrokhzad’s poetry reflects her belief that silence was not simply the absence of voice but a space where one could be reflective, refine, and rediscover oneself. In “Only Voice Remains” she celebrates the power of voice and underscores its relationship with silence. This idea for me became especially resonant after the sudden loss of my mother. Her death marked a profound silence in our home. Her voice that had once filled every room with warmth and energy was suddenly gone. In the aftermath, I found myself trying to preserve her essence through memory, writing down what I imagined might have been her grocery lists, and her recipes, recalling her favorite phrases and copying out the lyrics to songs she used to love. This process was not only an attempt to capture and hold on to her spirit but also a realization that silence could be an opportunity for reconnection. Farrokhzad’s idea that “only voice remains” spoke to me during this time, as I learned to bond with my mother’s spirit through the act of writing.

The understanding that silence and voice are not opposites, but intertwined, became clearer after my father’s death. The silence in our house grew deeper, and I began to reflect on how silence could shape identity. It was in this cave of grief, in “the silent darkness” that I began to understand the role of sorrow and contemplation in the creative process. Farrokhzad’s poems helped me make sense of this period in my life, showing that even in the depths of sorrow, the human spirit retains its capacity to express itself, find meaning, and resist being stilled.

I appreciated Farrokhzad’s insights further last year. Stricken by heartbreak and smote by an indescribable loss, my throat seized up as it might in a type of laryngitis and I was unable to use my voice. What I anticipated could not last more than two weeks, and put down to an infection, virus or allergy, went on for ten weeks. Doctors could not offer an explanation, and friends suggested it was psychosomatic. Initially, I was frustrated about my inability to vocalize my thoughts and feelings. However, after four weeks of struggling to whisper and write messages on Post-it notes, total silence followed and I had to accept what my body was signaling: keep silent. Silence became a form of surrender, and in that, I found a type of liberation from not having to ask or explain. I could be alone in my thoughts for days on end. At first, I discovered that I was listening more intently, more conscious of the sounds around me, and then, as the days passed, I found it was easier for me than it had been before, to withdraw from the world and tune out every voice. I hid in my silence, and found solace and refuge in it. When my voice returned one morning, in the same way as it had disappeared, without warning, it was as if a part of me had awoken again after having been buried, in a kind of hibernation, or a deep slumber. That feeling of dark comfort has not disappeared, and every so often the depths of it feels present. Yet, having my voice back again, did not give me a feeling that I had emerged more whole or reawakened to some higher self-knowledge or anything like that, but did allow me a deeper understanding of Farrokhzad’s assertion that even in the most profound silence, voice remains; it lies dormant and when ready, reemerges.

This idea of voice enduring, even when silenced, is a central theme in Farrokhzad’s poetry. Her work insists that voice, whether feverishly spoken, written, or almost dying and held in captive silence, is for her an essential part of what it means to be human. Indeed, when it was suggested to Farrokhzad that her poetry could be characterized as “feminine,” she answered, “What is important is humanity, not being a man or a woman,” she said. “If a poem can get to that point, it is no longer connected with its creator but with a world of poetry.” Her poetry offers a powerful reminder that an authentic voice always finds a way to survive, adapt and resonate.

As so many poets, journalists, writers and artists are targeted, killed, silenced, imprisoned and cancelled, and while others make efforts to keep voices alive, give them a platform and fight for the right to creative expression and be heard, Farrokhzad’s poetry remains an unwavering beacon, reminding us of how voice with its indomitable power, whether in defiance or reflection, seeps into time. The poem below is a tribute to her.

Voice, Voice, Only Voice Remains

If they silence us,

We will paint the walls with menstrual blood.

If they snuff out the candle,

We will whisper in the dark.

If they tell us to forget,

We will articulate a future on our own terms.

If they cut off our tongues,

We will speak using gestures.

If they tie our hands and feet,

Our words will find wings.

If they burn our words,

We will have photographs and art to immortalize.

If they trap the birds and bury the flowers,

We will lie on the grass, look at the sky and count the stars.

If they snatch away the clouds and lock up the rain,

We will keep holding our umbrellas.

If they take our memories,

We will create another type of forgetfulness.

If they extinguish the spark that glows in us,

The fragrance of those ashes will blow in the wind and reignite us.

If we lose our voices because of them or our ownselves,

We will excavate the remains in the silence.

To protest, to sing, for solidarity, to resist, for joy, for sorrow, for life and death,

We will use our voices.

Our voices echoing down the broken, empty corridors

And up through the cracks in the rubble

For all time.