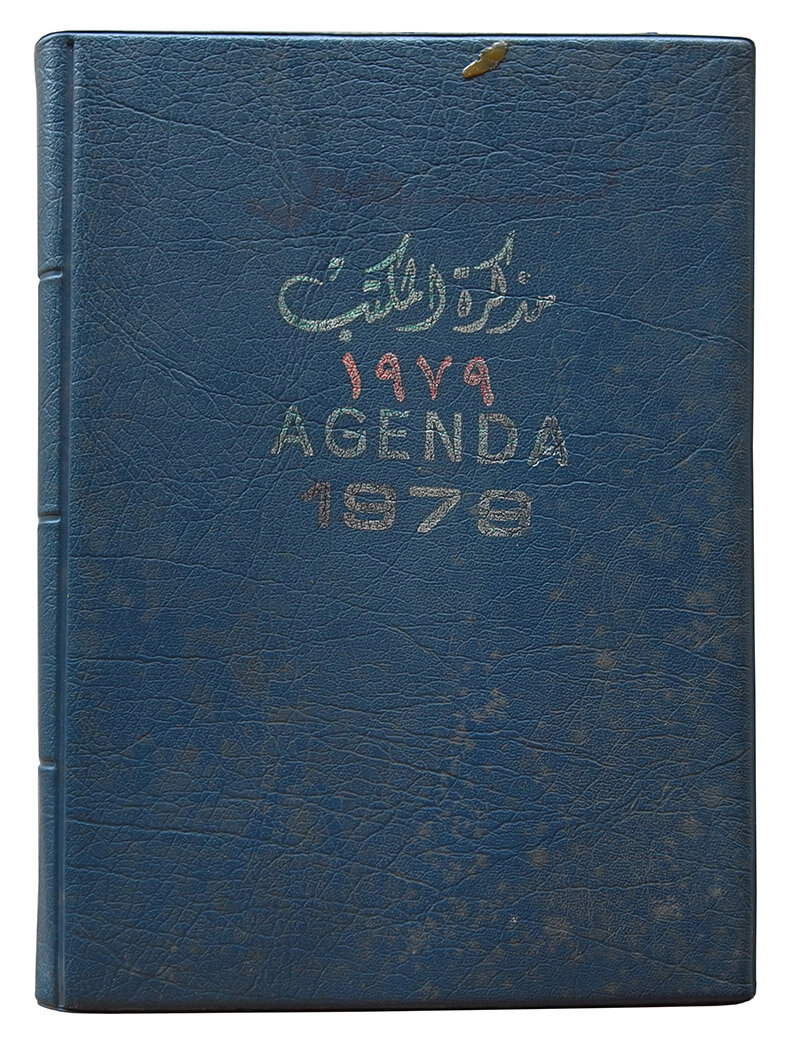

The Opera National du Rhin’s annual Arsmondo festival featured Lebanon in 2021, all online during the pandemic, and among the pieces commissioned was an opera-video performance, based on the journal of a Palestinian fighter found by a Lebanese photographer, Gregory Buchakjian, in an abandoned house in Beirut after the civil war. Buchakjian has done extensive work on Beirut’s architectural history and heritage, leading to Agenda 1979 by Buchakjian & Cachard.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

“To say nothing, do nothing, mark time, to bend, to straighten up, to blame oneself, to stand, to go toward the window, to change one’s mind in the process, to return to one’s chair, to stand again, to go to the bathroom, to close the door, to then open the door, to go to the kitchen, to not eat nor drink, to return to the table, to be bored, to take a few steps on the rug, to come close to the chimney, to look at it, to find it dull, to turn left until the main door, to come back to the room, to hesitate, to go on, just a bit, a trifle, to stop, to pull the right side of the curtain, then the other side, to stare at the wall.”

So goes the first stanza in Etel Adnan’s poem “To Be In A Time Of War” (2005), which summarized the use of a notebook, journal, or agenda, in times of disaster, in times of war. A situation when time becomes so disentangled that these pages are a window into the reality of the world, where you are still able to number things, count them, organize them, insert them into the continuum of life.

So many of these diaries exist for Beirut. And there will certainly be more for Gaza.

But there’s one diary, unlike any other: The Agenda 1979, at the heart of an eponymous experimental opera by the Lebanese trio, artist Gregory Buchakjian, playwright Valérie Cachard and musician Sary Moussa. This is not the passive account of an observer, waiting time out, and watching events unfold; it is not an account about war, but a manual on how to make war. This might sound uncanny, but the real events are less credible, less convincing, less conclusive, than any imaginary plots.

There’s a date: July 29, 2012. Buchakjian and Cachard entered (read: trespassed into) an apartment in a building on Rue Jeanne d’Arc, plot 335, in Ras Beirut. It was one of three identical buildings, in the French mandate architectural style of the 1930s, and the only one which was accessible, since it was abandoned after shelling in 1989. Inside this derelict apartment, two Palestinian lives coincided, though it was unknown whether they had been neighbors or lived in the same apartment at different times.

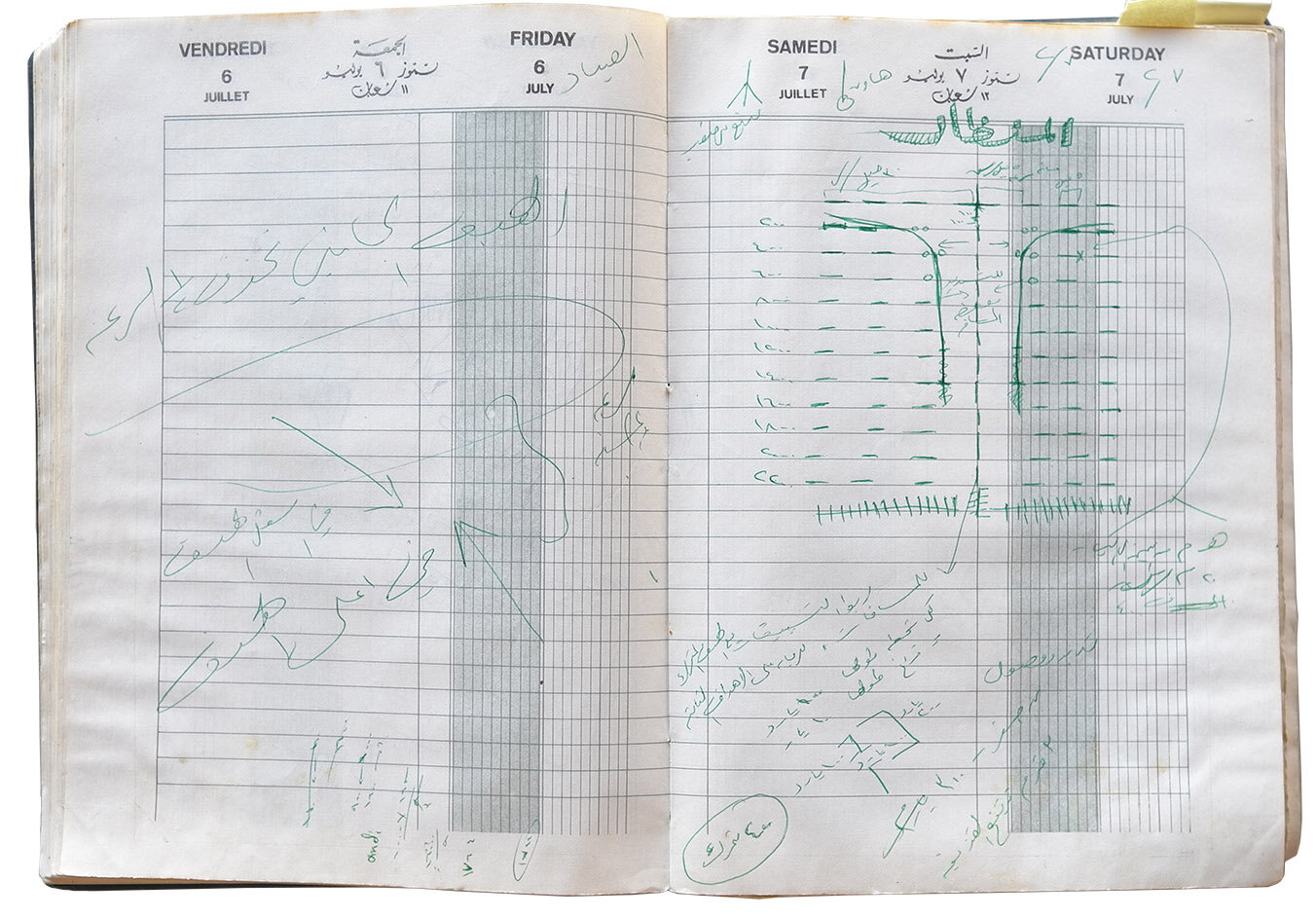

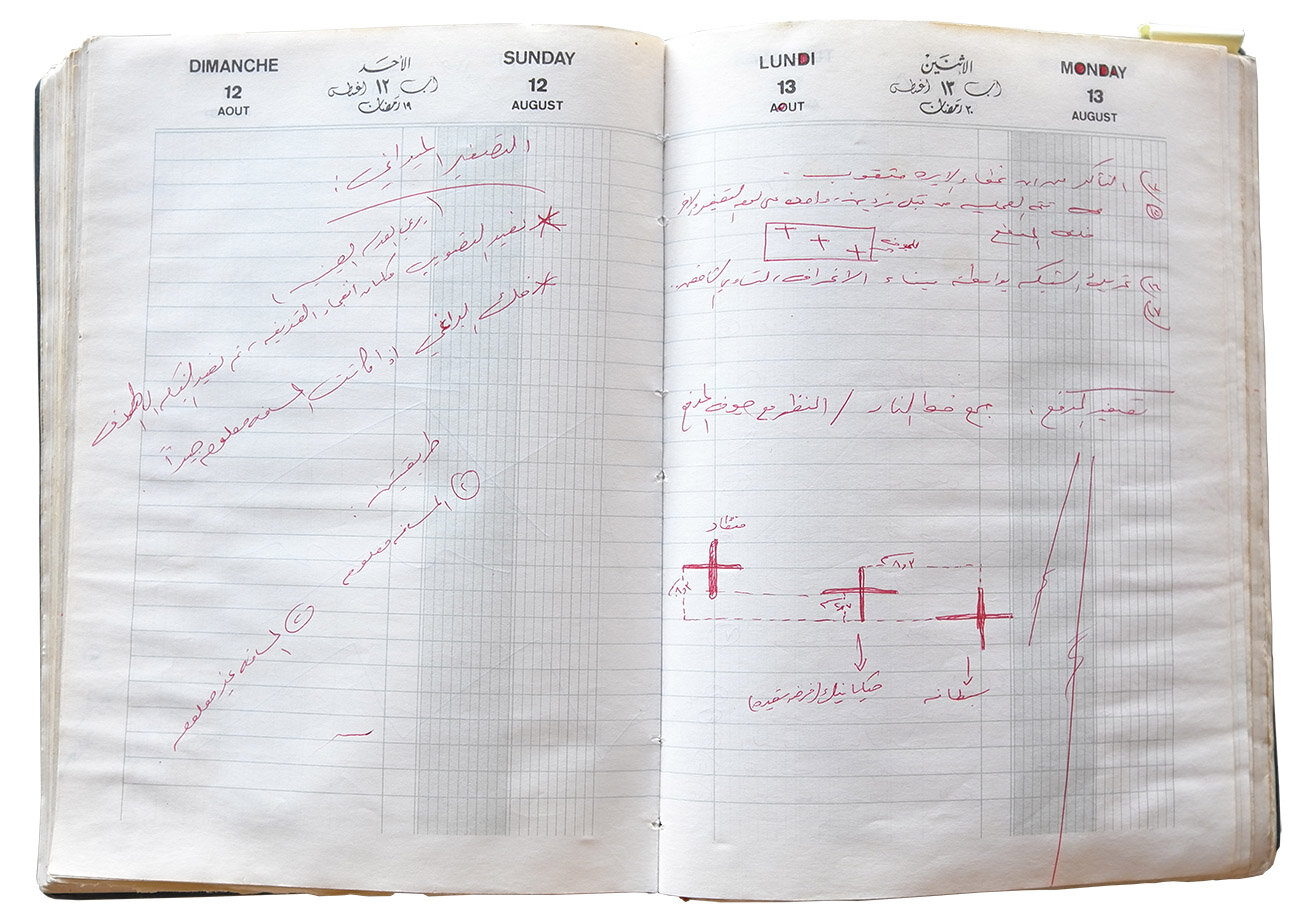

The first was Adnan K, who was born in Palestine in 1947, grew up in Amman, attended the American University of Beirut, and left Lebanon at an unknown date to settle in California. The second was Abu Said, to whom an office agenda for the year 1979 was addressed to, by Abu Awd, a member of the General Command of the Al Assifa Forces within the Palestinian Liberation Organization. This agenda, the Agenda 1979, is a manuscript memorandum written in Arabic, containing detailed descriptions, technical instructions and step-by-step graphic sketches: Weapons operation, homemade assembly of explosives, artillery ballistics and combat procedures.

We know little else about either Abu Said or Abu Awd, but this is of course not the known modus operandi of Palestinian or Lebanese militias, and more of an account by someone who received training in an artillery school, with the precision of an engineer, involving mathematical calculations and chemical reactions.

Other documents found in the apartment point us in a speculative direction: Six postcards depicting painted interior views of the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad, two reproductions of postcards depicting wilderness in the USSR and a reproduction of five stereo slides depicting sights of Leningrad. Was Abu Awd perhaps trained in the Soviet Union?

One of the slides depicts the Quay with Sphinxes on the Universitetskaya Embankment of St. Petersburg, the two ancient Egyptian sphinxes acquired by Andrey Muravyov in 1830 during a Holy Land pilgrimage, on behalf of Emperor Nicholas I, at the height of the European Egyptomania led by the discoveries of French orientalists. These slides, alongside a typewritten text by Buchakjian, briefly telling the story of Adnan K and the two Abus, with a succinct description of the agenda, were exhibited in Beirut in 2013, but the physical agenda was missing.

Stories begin to interweave: A bombing took place on Rue Jeanne d’Arc, in an attempt to assassinate a Palestinian militant in April 1982, reported by the photojournalist Georges Azar, but as it turns out, it wasn’t the same person, who was instead in the building across the street. Another journalist, Nora Boustany, offered Buchakjian to help track down Abu Said. But he refused. There’s just so much one can dig without becoming one with the excavation site.

Here, in the present, we read from Etel Adnan’s poem again:

“To put things in order. To find a 1975 diary. To read at random: “Back from Damascus”. To read, further: “Sunday the 12th. Mawaqif meeting.” To leave the notebook on the table. Turn the radio on KPFA. To absorb the news like a bitter drink. To create terror, that’s war. To wallow in cruelty, conquest. To burn. To kill. To torture. To humiliate: that’s war, again and again. To try and break the iron circle. To go downtown, at least, to park on Caledonia.”

When Gregory Buchakjian set himself to map and document through photography the abandoned houses of Beirut in 2009, the most crucial piece of evidence in the puzzle of the city’s absurd, protracted past, he soon found himself inside a chess board: The more he dug out of the archaeological record of the past and present, the deeper the drilling core became, and the more truth merged with fiction. The depth of the abyss only enlarged in time. No sooner than many buildings were documented, they became empty plots overnight, rapidly transformed or gave up to an architectural destruction more intense, faster, than that of armed conflict — the many reconstructions of Beirut.

Around 2011 Buchakjian and Cachard began not only to document the abandoned houses, but also to collect archives: They carefully sorted out through any material indications that could give some clues as to who the dweller was; utility bills, postcards, letters, photographs, business cards. What kind of evidence for our lives would we leave behind if we left our homes in a haste, forever?

Some questions are to remain unanswered. Is the person alive? Do these abandoned documents tell a story that they wanted to forget when they hurried out? Or are these precious memories for someone? And the value of the photographic document itself: Are these photographs taken by Buchakjian really documents?

At the conclusion of Buchakjian’s project, he and curator Karina Helou, were preparing for a major exhibition at the Sursock Museum in Beirut, “Abandoned Dwellings, Display of Systems,” and while discussing the archival material to be included in the exhibition, the infamous agenda came to mind. Ultimately, the artist decided not to include it, in spite of its unmatchable importance as a document, because he deemed the material too violent, and thinking that it was perhaps unnecessary to reactivate past trauma.

The agenda remained in a dormant state. Yet, as a part of the Sursock exhibition, Buchakjian, Cachard and Moussa collaborated in a short video, “Archive,” in which they laid out vast amounts of the archival material and sorted it out, unsure whether it was a performance or a forensic investigation. The agenda reappears here as a sheer object among many, lost in an interminable stream of assembled traces — an assemblage without any particular direction. Dormant, however, means also latent, ready to awake at any time.

And then, another date, the ultimate date, after which the measurements traditionally applied to war became useless. August 4, 2020, shortly after 6 pm, the event horizon of Beirut. An explosion unlike any other, when a cache of approximately 2,750 metric tons of ammonium nitrate precariously stored in the port of Beirut, set off an explosion so massive that it destroyed large sections of a city, then still only partially rebuilt. A grand finale; to explode what had exploded once before, to explode what hadn’t finished being rebuilt. According to scientists, the Beirut blast was so large, so devastating, that it disturbed the upper atmosphere above the city and changes were observed in ionospheric electrons, comparable only to recently recorded volcanic explosions.

What could these numbers mean here? What does war mean anymore in the face of this impalpable destruction?

Etel Adnan answers retrospectively in her poem:

“To program chaos, to make sure that it will be a killer, to prevent a country from being managed decently: that’s the day’s politics. To pervert language, pervert the children’s eyes, corrupt and destroy, that’s the new order. To distribute evil with specially built machines […] To destroy both the inner and the outer wall. To inhabit the city which has been conquered by murder. To add ruins over ruins. To be jealous of Babylon. To spray hatred on its corpses as well as on the living. To burn live matter. To water the palm trees with fire; that’s a barbarian’s job…”

Only now, Agenda 1979, the notebook unlike all other notebooks, would rise to the occasion, to match the event unlike all other events. Agenda 1979 was about to awake from its dormant state, not in the form of a handbook of warfare and combat, but as an elegy.

After having found Buchakjian’s book Abandoned Dwellings that accompanied the Sursock exhibition, Christian Longchamp, the director of programs at Opéra National du Rhin, in France, contacted Buchakjian to invite him to participate in the performing arts Festival Arsmondo 2021, dedicated each year to a different country, and for this year devoted to Lebanon. The pandemic forced the festival online, in a more interdisciplinary form, across music, opera, film, literature and the visual arts.

Reflecting on how his practice could be presented in something like an opera setting (whether virtual or not), Buchakjian decided to work on a new piece, with a very short deadline, that would involve sound, or perhaps that it would be only a sound piece.

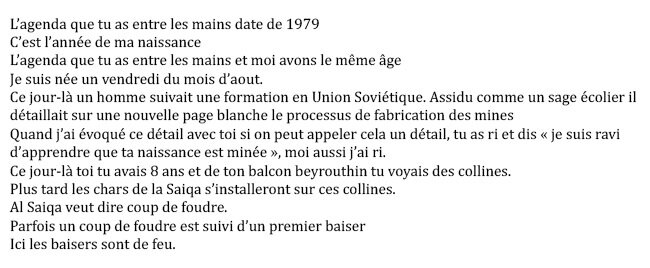

He contacted Valérie Cachard and Sary Moussa to collaborate again, and then, an operatic idea came into being: resurrecting the agenda. Buchakjian’s initial proposal was to read the entire content of the agenda in Arabic, into an opera of about four hours, clinical and neutral, over which the voice of Valérie Cachard and the music of Sary Moussa would overlay. At first, the text needed to be typed since it was difficult to read the fading pages, riddled with technical terms. He typed and recorded the contents corresponding to less than one month of the agenda, and it was a 40-minute recording. Then he sent this recording to Cachard. She began building the piece based on the reading, in the form of what she calls in the script, sound postcards. She introduced stories and conversations she would tell someone — Buchakjian, but this isn’t always clear. The final piece is close to 20 minutes long.

In the French script, the delicate voice and mesmerizing fragments of Cachard not only interfere with Buchakjian’s clinical reading, but provide a double trace: These precise instructions for war, methods, analytical skills, and measurements, they are now events. Events that have taken place; at the edges of which they inconsolably sit (translations mine):

“The diary you are holding in your hands is from 1979

That was the year of my birth

I am the same age as the diary you are holding in your hands

I was born on a Friday in the month of August.

The very same day, a man was undergoing training in the Soviet Union. Like a studious schoolboy, he diligently detailed the manufacturing process of landmines.

When I pointed this detail out to you, if indeed it is a detail, you laughed and said ‘I am pleased to hear that your birth was mined.’ I laughed too.

That very same day, you were eight years old and from your Beirut balcony you could see the hills.

Later As-Sai’qa tanks will settle on those hills.

As-Sai’qa means thunderbolt.

Sometimes a thunderbolt precedes a kiss and singing in the rain.

Here the kisses are made of fire.”

It is a sound postcard not about the document itself, the artefact, but looking deeper into the possibilities of reality —the event is always the creation of new possibilities. What if this agenda was not a harmless artefact collected from a pile of documents strewn on the floor or forgotten in drawers?

Curator Karina Helou told me recently: “Valérie and Gregory delved into this archive again, without the intention to reactivate it, but on the contrary, exploring the trail of violence left by such innocent looking objects as this agenda, which led to monstrosities being committed and to the development of warfare. Valerie’s soft voice, in dialogue with Gregory who reads as a background noise in Arabic the content of the agenda, marks the end of innocence.”

“You tell me it is a banal and terrifying object.

You also tell me that this notebook contains what it takes to blow up a country.

Do you think we need a notebook to blow up a country, to blow up our country?”

“You tell me that this diary is a time bomb.

You tell me that on Monday, December 24, 1979, they speak of the importance of proper maintenance and storage of explosive materials.

You add: ‘Monday, December 24 can’t be a joke.’

No it can’t be a joke.”

Imagine sitting at home, in the presence of a handbook for destroying, bombing, maiming and injuring. A handbook with precise instructions, in which there’s no mention of a known enemy, but an unknown other, a generic somebody, described in the petty technicalities of the distance at which an anonymous someone should be in order to receive injury or retreat back to safety.

Then imagine this, in a country that was already destroyed, more than once, more than twice, more than many times. But it’s not necessary to imagine. There’s a page for August 4, 1979, with a graphic chart that depicts something like the pattern of waves traveling through a medium, or the different points of contact in the sequence of a detonation. But what do we know about bombardment anyway? Beirut has ever been only on the receiving end, without a manual of instructions.

Cachard interjects,

“Why do we do this?

Is it art?

Is it survival?

Nowadays is making art survival?

Despite the luxury of having a full fridge, a comfortable bed, a pleasant apartment and some heating?

I’m sorry but I’m having a really hard time getting into it. Really. It’s hard. I’m sorry.”

The événement of Beirut is an ungraspable situation in which a multiple (a term borrowed from Badiou, to refer to anything that is not a singular or the whole) does not make sense according to the rules of reality, and needs to be intervened, in order to change the rules of the situation, and insert a possible meaning that might transform this situation into a real event. But how now? When the événement has become a singularity? An absolute future without past, and without end.

There is here an incredible degree of sublimation in the contrast between Buchakjian’s reading and Cachard’s loose poetry, a sublimation in the form of surrender. But what the artists are surrendering is not themselves; it is the concepts, strategies, utterances and possibilities of reason, art and language.

At some point in the narration both voices become muddled into a thick, undecipherable cosmic background, drowning in the synthetic noise arrangements of Sary Moussa, somewhere between lament, drones buzzing, composition and danger warning.

In front of us, the numb audience, puncturing the sounds, there are images of the Lebanese skies, from Jabal Kneisseh and Jabal Sannine, the two peaks dominating Beirut, and the most ubiquitous theme in the history of Lebanese modern painting. But what you can see is mostly fog and clouds, an abstraction, an approximation to a place, or the vagueness of an undefined, incomplete event. How is it possible to speak of war, of violence, in the face of such ineffability? The artists’ choice was not to address, but to point at something, to attempt a definition in vain, and to make you a participant in a search, in a futile search, a rescue search without survivors. The event of life, of the world, will have to be reinvented in its entirety.

Time stands still in Agenda 1979, or at least is bereft of direction, temporarily, so that you can sink completely, to the point of surrendering your own strategies of language and reason as well.

From the blur of the mountain range, all that you can see of Beirut right there, sometimes occasional rays of light emerge which speak to us directly, in the language of revelation. They tell us that salvation is no longer possible or available, this time around, but maybe some other time. This negation brings to mind the words of Jacques Derrida, in his obituary for Sarah Kofman, after her untimely suicide in 1994: “This ray of living light concerns the absence of salvation through an art and laughter that, while promising neither resurrection nor redemption, nevertheless remains necessary. With a necessity to which we must yield.” It is imperative to remain awake to the very end, or paraphrasing Philip Azoury, in the absence of an entire event missing, the next logical step is to recount a nonevent.

When Gregory goes up to the mountains to film, Valerie writes, altering the temporality of the script,

“Today you are in the mountains.

You search, you stop, you film.

You send me a message.

You are cold.

You are shivering.

The landscape is splendid.

The camera is rolling.

The day is waning.

The cold is bone chilling.

You remember a painting by Simone Fattal.

There is a mountain and some blood, a painting inspired by the battle of the peaks of Mount Lebanon.

Perhaps the battle took place on Mount Sannine?

You saw that painting in her home.”

I keep wondering if Etel Adnan had also seen that painting, at the apartment they shared with Simone in Manara, when she wrote the last stanza of the poem, or if she referred to one of her own:

To try and be distracted by poetry, by trees. To see the trees grow, in a hurry. To appear and disappear. To take refuge from bestial conquest in false shelters. To chase the refugee, to flush him out of his new refuge. To lodge a bullet in the head and back of a Palestinian. To add Iraqis to the butchery. To paint big canvases with blood, then take a night train, then a plane. To disembark in Paris. To pick up the telephone, dial a number for Beirut. To hear the friend say that a Palestinian newsman has been cold-bloodedly shot by some earnest monotheist. To wonder on the necessity of God. To brush the problem aside. To think of Cassandra. To remember the Hammurabi Code. To sink in fat. To look at the narrow and long road which leads the world to the slaughter-house.

And so on.

Gregory Buchakjian (b. 1971), is an art historian and interdisciplinary visual artist, he earned his PhD from Sorbonne University and is the director of the School of Visual Arts at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts. His research and practice deals with modern and contemporary art in Lebanon with a focus of the city and its history.

Valérie Cachard (b. 1979), is a writer and playwright. She completed studies in French literature and journalism at St. Joseph University and the Lebanese University. She was appointed in 2019 co-chair of the International Commission for Francophone Theater and is a recipient of the RFI-Théâtre Prize for her play Victoria K, Delphine Seyrig et moi or la Petite Chaise Jaune.

Sary Moussa (b. 1987) is an electronic musician, active in the Lebanese underground scene since 2008. He released his first full length album Issrar in 2014, under the moniker radiokvm. His latest record Imbalance is rooted in the soundscapes of the country’s unrest and his personal recollections. Moussa has also composed music for theater, dance performances, short films and museum installations.

Etel Adnan (b. 1925-2021) was a writer, poet and painter, born in Beirut but based in Paris and the United States, and arguably one of the most celebrated Arab American writers living today. In 2020 she was a recipient of the Griffin Poetry Prize for her book Time. The poem “To Be In A Time Of War” appears her book In the Heart of Another Country” (2005).