Aomar Boum (UCLA)

With Majdouline Boum-Mendoza (Brentwood School)

Feeling at home among family has different meanings for each of us. For Mohammed, my late brother, it meant taking a breath or breathing oxygen to stay alive. It also meant being an inspiration and lighthouse for his extended family and fellow villagers.

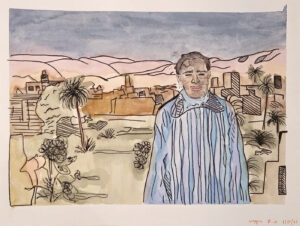

My older brother Mohammed Boum died on January 12, 2023, after a long struggle with labored breathing and air hunger, a result of many years of inhaling toxic smoke that reduced the functionality of his lungs to less than 20% of their capacity. My daughter Majdouline and I were in Morocco and able to see him the month before he passed away. To honor his memory and his family, we have written this short encomium.

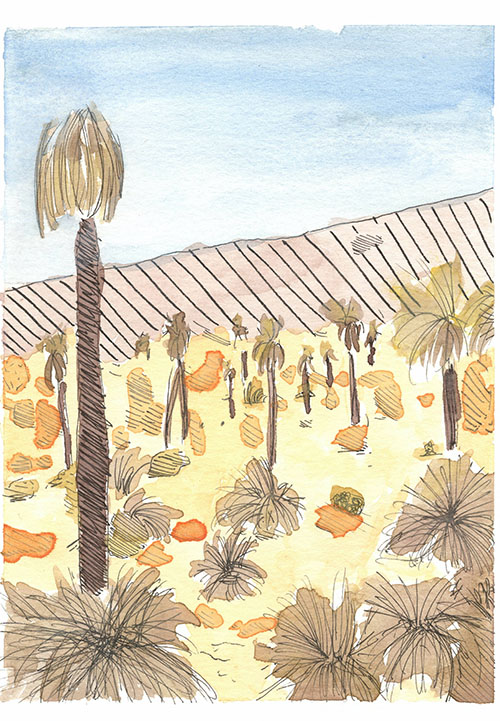

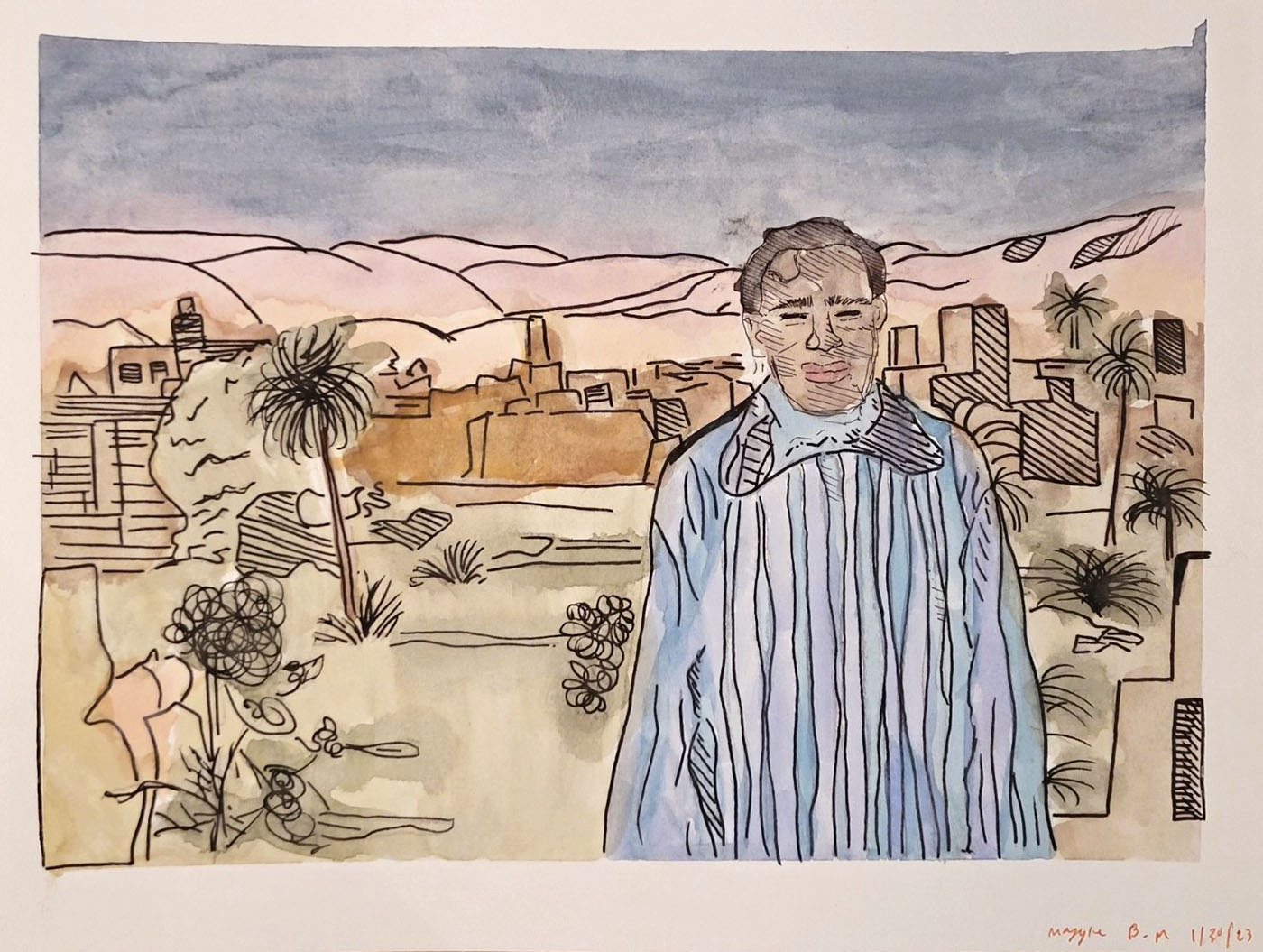

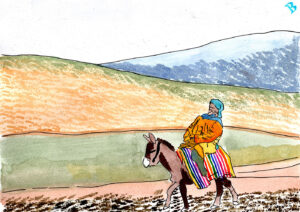

Seizing the opportunity of a conference on “Memory and Identity” in Agadir, I brought Majoudline with me to visit with her grandparents in Morocco’s Anti-Atlas mountain belt. This wasn’t the first time she traveled home with me; over the years, she has accompanied me almost every summer during my family visits to the southern region of the country, where my parents still reside. This time, however, Majdouline had not seen her extended family since the pandemic, and much had happened since we last visited the town. The people of Lamhamid had died of Covid, a severe drought had impacted the region, and a lack of water had gripped the palmeraie. Erstwhile evergreen palm trees were left with nothing but dry fronds. As a result, people had left for cities and even abroad in search of better opportunities. Amidst these changes, the thing that was most noticeable for me and Majoudline was Mohammed’s failure to recover from the breathing problem we had witnessed five years earlier. It all started in 2018, when Mohammed began to experience a constant cough accompanied by weight loss. After much resistance, he caved in and paid a visit to a doctor when my mother insisted that he seek medical help. My brother was not an exception in his reluctance; people in my village rarely go to a doctor. They were never socialized to seek healthcare, a situation that is exacerbated by the absence of dispensaries, hospitals, and doctors in these remote towns and villages on the northern edge of the Sahara Desert.

Born around the first decade of Independence, Mohammed was the fourth of nine children. Growing up in the 1960s — a time when school and education were not available to many people — he joined my father as a day laborer to provide for the family. As early as the late 1960s, Mohammed was already clearing small farming lands from rocks, digging wells, watering farming plots, cleaning water canals, harvesting dates, and clearing manure left by sheep. In his early twenties, he opted to leave the village for a better paycheck, one that could help him provide for our father, who continued to struggle financially.

In the 1970s, Mohammed traveled to the southern city of Goulmim, where he spent years digging wells and inhaling toxic gas and noxious particles from gunpowder. As Mohammed inhaled smoke inside the wells, all the while causing acute injury to his lungs, my father slowly built a financial cushion that allowed him and the rest of the family to afford a relatively comfortable living. Realizing the toll well-digging took on his health, Mohammed turned to construction, especially as Goulmim witnessed intensive urbanization following the 1975 Green March, which King Hassan II organized to reclaim the colonized territory known as the Spanish Sahara.

Mohammed’s experience and work-related resourcefulness did not stop in the south. He moved to Casablanca, where he worked as a kassal (masseur and body cleaner). For people from our region, working in Casablanca was almost a rite of passage, and the big city was known to attract most of its masseurs from the southern desert province of Tata, one of Morocco’s poorest areas. Although the work required a lot of effort in damp and hot hammams, the compensation depended on the generosity of the client. Needless to say, working in humidity over long years exacerbated Mohammed’s respiratory issues. Realizing that this job affected his health, Mohammed moved back to the village in the mid-1990s. From then until his death, he stayed in the village, where he and his family lived with my parents in the same household.

His return to the homestead allowed Mohammed to slowly and silently build a social network throughout the village. He opened a bodega-like store that catered largely to women; he sold blankets, tea, sugar, traditional herbs, cooking utensils, and anything the isolated villagers needed for their quotidian uses. All his transactions were in cash, and he never took a loan or credit. (Loans with interest rates are prohibited in Islam.)

Mohammed did not have a bank account. As a result, the form of economics he practiced was socially responsible; those who had money paid right away, while those who could not do so were allowed to pay when they received remittances from their family members in other cities or abroad. Upon his death, many of the people who owed him money showed up to clear their record with him. A Muslim is supposed to pay the debt to the heirs if the creditor has died. Similarly, if one is indebted but dies before paying his debt, his family has the moral duty to clear any and all outstanding payments. As a family, my brothers and I made sure that Mohammed’s record was clean, that he left no credit.

Mohammed’s value to the village and his large network of connections locally and beyond became apparent to me after his death. In Los Angeles, my phone kept ringing for weeks, with people calling from France, Spain, Casablanca, and the village. These people felt his loss and wanted to share it. Mohammed had a special way of maintaining relationships. He would call people just to check on them. This extended to me as well. He would always insist that I give a call to someone who lost a family member or whenever someone from the village died.

His friendships increased over time and people turned to him for help with different things. For many, Mohammed was a de facto trusted general secretary of the village. He was entrusted with looking after the local residences and businesses of villagers who lived abroad or in Casablanca. For migrants, he was in charge of supervising construction projects and paying electric bills. My brother held such a vast reserve of social capital that families sought his advice on a bride or bridegroom. His own immediate family, particularly our sisters, reached out to him when their children faced life issues. Economically struggling households turned to him for assistance when they needed financial support. Mohammed was always there for everyone. He went an extra mile to help needy people in our community by reminding me to send donations to widows, orphans, and others in need. Without knowing its theoretical implications, Mohammed practiced a solidarity economy.

Life and careers took me and my other brothers out of the village, and Mohammed slowly became the pillar of the household, replacing Faraji, our aged father. Faraji, who had been the patriarch of the family until early 2000, quietly stepped aside as Mohammed took over the responsibility of managing the family’s daily matters. It was the natural and expected process of intergenerational transition, and Mohammed was prepared for it. Although extended families were slowly being phased out as traditional family units broke up into smaller nuclear families, Mohammed insisted on keeping our larger household tight. Even when other brothers moved out and chose to start their own nuclear families, Mohammed preached family and community until his last day in the world.

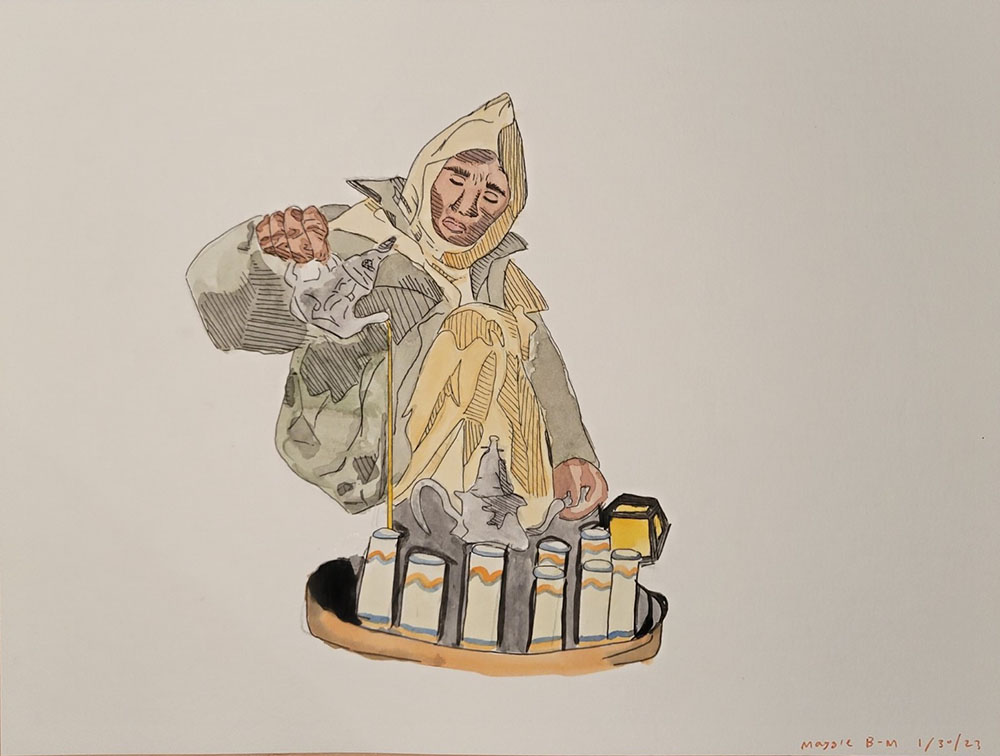

Making tea was one of the skills that Mohammed learned during his time in Goulmim. Tea-making is not just a social ceremony; it is also a moment of social and family cohesion and solidarity. Every day, after the Maghrib prayer, men gathered around in a circle in front of Mohammed’s shop to drink tea and discuss the daily events of their life. After the Isha prayer, Mohammed would usually take charge of the ceremonial tea-making after dinner as the family congregated to listen to the news on TV even as they engaged in conversations that drowned it out. Television was a reason to bring people together, but tea and conversation were the most important part of the evening.

Mohammed’s presence in his village and family circles will be terribly missed. However, his life journey and sacrifices on behalf of his family and community will continue to live. The stories they tell about him will continue to breathe life into his memory despite the fact that dust in his lungs meant that he breathed his last on January 12, 2023.

Many thanks to Brahim El Guabli and Norma Mendoza-Denton for their valuable edits and comments on this piece.

Thank you Aomar. Thank you Maggie. Tear drops as I read this portrayal of Mohammed’s life journey – breathing life into family and community as his own diminished. You brought Mohammed to me, and I am ever grateful for this connection, made vivid through remarkable images and tender prose.

Thanks si Omar for this vivid portrayal of social and family life in southern Morocco. I have recently paid a visit to my parents oasis Tagmoute in the province of Tata. A very poor area with courageous people.

May the dead ones rest in peace.

Thank you, Maggie and Aomar, for this amazing testimony and for honoring Mohammed. As someone, who knew him for many years, this article is spot on and put light on a small portion of Mohammed’s legacy. Rest In Peace, you will be greatly missed and continue to be a source of inspiration for many generations to come.