Memoir of an unjust death and the spirits who return to protect the living.

Dia Barghouti

I sit. I get up. I sit. It is time. A driver waits outside. I do not move. My stomach turns. I get up. I decide to clean. I am surrounded by scribbles of paper. Words. Time dispersed in a multitude of forms. I dispose of them, hoping for an end. The night persists. I wait. The driver waits. I feel we are moving closer to the void. The void that is the beginning. I wonder if this is existential angst. Surely not, a war begins outside. The perpetrator is the same. Time assumes a new quality. I discover a feeling beyond angst. A spider appears. This too is its home, like myself it has not yet mastered the language of conquest. I try to distract myself with a book. Poetry that never ceases to subsume new forms. Human beings are a wonder! Destruction and beauty are intimately intertwined. In suffering the beautiful itself is transposed. Or at least that is what has been written by the 12th century saint. I try to find solace in ancient words. The sound of planes lingers, its victims in nearby vicinities where it cannot be heard. I am not yet the target. The phone rings. I answer. A voice tells me the end is near. Yet the night persists, mercilessly. I walk to the window. I am certain they will arrive. It has been announced. The driver honks. I sit. Something feels unfinished. Perhaps I am meant to die here or compose a line of poetry. One day this night will mark a moment in “history.” But there is no longer “history,” only violence. Rotting corpses that lie above the ground they want to make their “summer homes.”

A retaliation is inevitable, as is the retaliation to the retaliation. Suspended in this obscure moment in time, I wonder if this is the end we have been promised. Given that nothing is infinite other than the infinite itself there must certainly be an end. I walk to the window. A deafening silence. It terrifies me. I pick up a scribble of paper and write “there is no salvation in purgatory, only time, infinite time beyond which there is only a vast nothingness.” I laugh. I can be very dramatic sometimes. The driver honks. The sound is more faint. I walk to the kitchen. Surely this drama cannot continue to unfold without a coffee. The phone rings. I take the first sip. A man tells me to evacuate. I sit. I light a cigarette. I take another sip. A sound emerges in the distance. Then silence. I turn on the radio. “A ground invasion is inevitable.” As is the invasion following the invasion. It was only a matter of time, or, as they saw it, preordained destiny. Theirs is to annihilate us, ours to subsist.

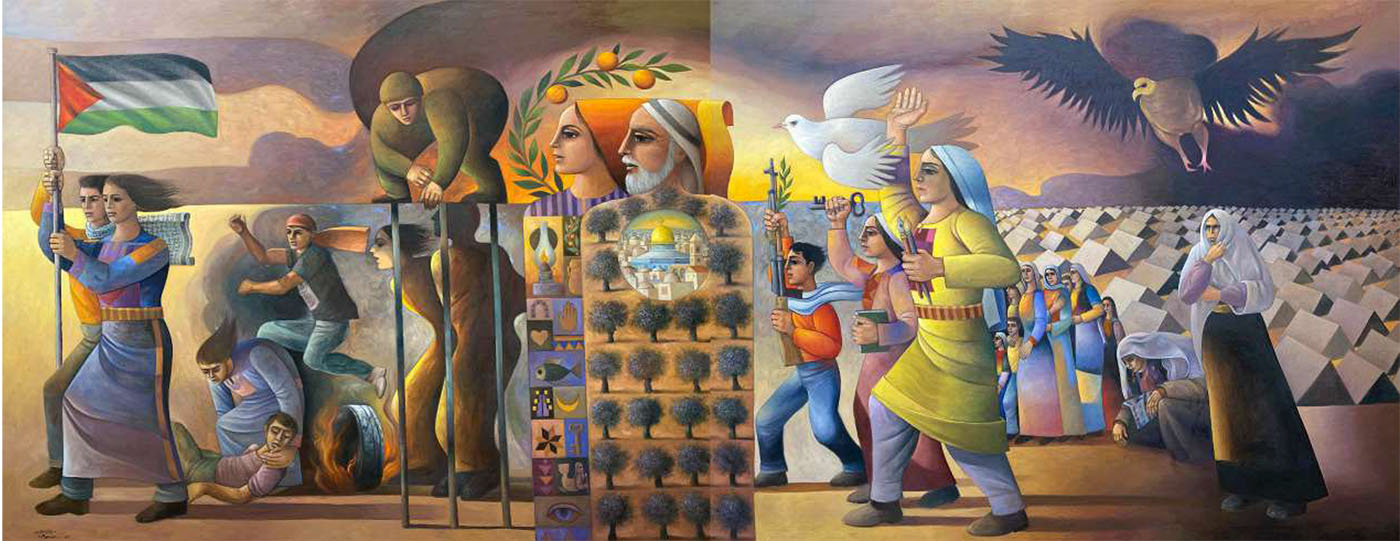

I open the door. A corpse appears. Its head is severed and the night wind smells of lavender, reminding me, by God’s grace, that the prophets had once walked upon these lands. I close the door. I sit. The silence is interrupted by the sound of the car departing. I take a sip of coffee. It suddenly dawns on me: I am late to a wedding. I put out the cigarette. I get up and linger in hesitation, contemplating if I should light another cigarette. If I leave, they might invade, and if they invade, I cannot return. I walk to the closet and put on my best velvet; it is, after all, meant for festive occasions. I walk back to the kitchen and open the door. The corpse is still there, the head no longer severed. I close the door. I sit. The irony of the situation disturbs me. How can it be that we rely on the dead to protect the living? I try to remember the words. I reach for the book of 12th century poetry. 167, on existential wounds. Can I call a genocide “an existential wound?” Or is it the existential wound par excellence, as it casts doubt on the very purpose of living? Is it not absurd to ask oneself these questions when death is quite literally right outside the door? Or is it that we are the only ones left who embody this truth? The only ones who are able to contain this paradox with the infinite? Perhaps it does not matter, or perhaps it is the divine decree, our final moment in God’s vast earth. But even those who have read the writings of the 12th century saint will not understand this. To endure the very limits of what it means to be human is the only way to understand. To endure suffering, imprisonment, the diseases caused by siege, amputations of limbs without anesthesia, death, at this point one has attained sainthood. It is the dead who protect the living.

I am trying to determine when it would be possible to leave, and return of course. I would not leave if I was not certain of the return. Obviously, one can never be certain about anything around here, colonialists are terribly unpredictable.

I open the door. The corpse has disappeared. I hear women singing in the distance with death’s rhythm in the background. I close the door. Their singing can still be heard. It was not long ago that death was a rare incident that merited the most beautiful of processions. Now it has become unnaturally common and most of these songs have been lost with those who sang them. I walk to the window where I notice a flickering light. I wonder if this is the beginning of an invasion, but all I see is a turquoise-colored bird that perplexes me because they do not usually appear in the night. Who’s to say what’s “usual” anymore? I breathe in the gentle mist as I recite a litany to calm my nerves. I end it with “and it flows through the multitudes of time as does the sun in every universe.” The phone rings, giving me no time to meditate on the beauty of this sentence. “You are late.” I suddenly remember the wedding and walk frantically towards the kitchen and put on my shoes. I sit for a moment and think of that final sentence “the multitudes of time.” Of course this English translation does not convey the beauty of the original. Arabic is such a poetic language. It is no surprise that it has this miraculous ability to embody this relation with the infinite and its endless appearances through time. Someone bangs against the door. Startled, I fall off my chair. I decide not to open it as I suspect it is a soldier. Palestinians don’t knock that way, with unnecessary violence. It could be an invasion, and an invasion means certain death. I light a cigarette, wondering if it will be my last and wait to see if the banging will resume. It doesn’t and all I am left with is an uneasy silence.

I wonder how long I will have to wait. I am already late. I walk to my room, which overlooks the courtyard, to see if they have left, the only noticeable thing is my beautiful bougainvillea that complements the Ottoman architecture. This home has been in my family for generations and like all generations before I have exquisite taste in garden landscaping, our philosophy being “plant whatever you feel like.” Indeed, the garden itself is the product of successive generations of planting whatever we felt like. Due to our symbiotic relationship with the earth, and its many creatures, these “random” acts constructed the most beautiful of gardens.

But this is beside the point which is that I am trying to determine when it would be possible to leave, and return of course. I would not leave if I was not certain of the return. Obviously, one can never be certain about anything around here, colonialists are terribly unpredictable. Or perhaps to us (I believe the fashionable term these days for us is the “indigenous”) they seem unpredictable, but every action is part of a thoroughly devised insidious plan. Yet for us, this meticulous planning, including the most minute details of how to make a person’s life torture, is received in the form of deep uncertainty. Perplexing is it not? Or perhaps there is no point to the question, one must go on living, or at least try. I am late to the wedding. I take one final peek from the kitchen window and although I see nothing beyond the yellow roses, I assume the silence means the soldiers have left.

I open the door. I am shot. I fall to the ground as I bleed all over the velvet that belonged to my mother and her mother before that. In this moment of grave danger my first thought is how to save the velvet, it is a family heirloom. I then realize that the bleeding is quite severe. I slowly crawl to the phone while trying to put pressure on the wound. It rings. I answer. “You are going to die.” Silence. I close the phone and try not to panic. It is well known that this is an Israeli tactic of intimidation. I call an ambulance. The voice of the operator sounds more terrified than mine. At this point I am certain that much more is happening outside. He tells me to remain calm, apply pressure on the wound. He is sending an ambulance.

I wait. Time passes. Nearly every part of my body is now soaking in blood. I decide to call the ambulance again. As I had suspected, the operator tells me the Israeli soldiers will not let the ambulance through. “But do not worry,” he says, “we will get to you.” I crawl to the radio, with one hand pressing against the wound. The more time my body has to realize the trauma, the more painful it becomes. The smell of blood nauseates me, and I begin to feel faint. I turn on the radio. “The ground invasion following the attempted ground invasion which began in the North has begun.” I turn off the radio. The phone rings, I answer. “The ambulance driver is dead.” Silence. Was he really dead, or is this yet another Israeli tactic of intimidation? I walk to the balcony. If I’m going to die, I should like to do it while looking at my garden. I’ve already told you about my bougainvillea, but what you do not know is that every form of sustenance that you could possibly need can be found in my garden. Naturally, this is done without any planning. It is a very European thing to plan with great detail, with little understanding, that abundance comes not from the “scientific” approach, but the realization that the earth is the very expression of the infinite, and therefore, naturally abundant, if you plant to its rhythms, that is. This creates a new kind of music, inaudible to human beings, of course, yet it is the very principle that sustains existence as we know it. Despite the extreme pain, this thought makes me smile. I’ve always been a great lover of what is commonly known as “metaphysics” or what Sufis call “the sciences of the appearance of light from infinite non-existence.” I take one last glance at the garden and the vast expanse beyond it then fall to the ground. Getting murdered is effortless, if you are Palestinian that is.

I give into my fate, to be one of the 50,000 to give cadence to God’s vast earth. That is why so much emphasis is placed on funerary rituals, if Palestinians are able to retrieve the body, of course. I let the world permeate me and I became the world. It is difficult to describe the sensation of dying, but you might say that it feels as if there are no longer any boundaries separating you from the world. Other than parting with your body, you also experience an altered state of consciousness, far too complex to describe. There is no need to know about all that, not at this point anyway, let me finish the story.

Two Israeli soldiers walk into my house. They look over my dead body. One of them steals the ring on my right hand. The other walks to the balcony to see if there are any other Palestinians he can shoot. I hear my neighbor screaming. Uncertain about how to do so without a body, I decide to intervene. Normally, the dead do not interfere with the affairs of the living, but you see the injustice was grave. And even though everyone knew, or, perhaps more accurately, everyone who had the power to stop it knew, they did not intervene. It is the dead who protect the living. I begin to make loud noises around the house to distract them from my neighbor, who was now, along with her infamous dog Simsim, fleeing for her life. The first soldier, let us call him Soldier 1, now terrified, shoots without restraint at nearly every corner of the house, ruining my perfectly ordered furniture and killing Soldier 2. In a fit of rage, at his own idiocy, he opens the kitchen door to follow my neighbor, I presume his intention was to murder her too. And this is when something truly miraculous happened, primarily because I did it without having a body. I placed my foot in front of his and he tripped, accidentally shooting himself, and died. Reassured that my neighbor was safe, at least for now, I walk back to the balcony to recite a prayer. It is a strange thing to recite a prayer upon your own dead body, I suppose I should call it a “corpse,” but seeing that no one else could get to it, I had no other choice. It reminded me of the story of how Moses had once recited a prayer at his own grave near the red sand dunes visited by pilgrims every spring. And so I recited that same prayer, ending it with the verse “and it flows through the multitudes of time as does the sun in every universe.”