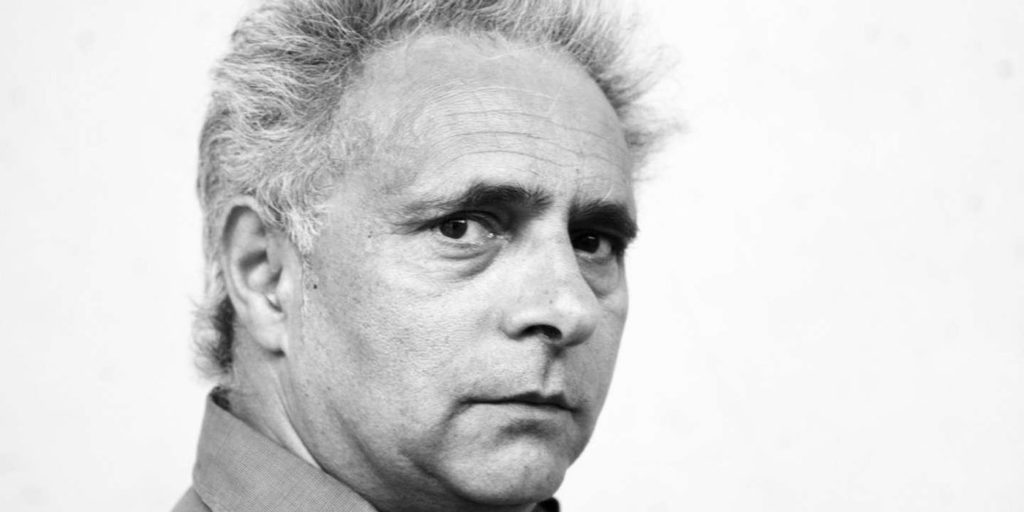

Hanif Kureishi

All first novels are letters to one’s parents, telling them how it was for you, an account of things they didn’t understand or didn’t want to hear, saying what couldn’t be said, providing them with a bigger picture.

It was the late ’80s, and I was in my early 30s, when I began to work on The Buddha of Suburbia. The two films I’d written previously, My Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, had bought me time and money. The success of My Beautiful Laundrette had given me confidence that the writing tone I’d found, could be extended into the novel I’d wanted to write as a teenager.

I had been no good at school, but always felt more alive than the people around me. I was a horny bookworm, and novels got through to me. I thought I’d do one. I did several.

They were not published. But I did write what became the first chapter of The Buddha of Suburbia, as a short story for the London Review of Books, published in 1987.

I believed that was that. Then I kept thinking there was more material. I had an intense experience which can happen to writers, when you understand that your subject is right there; you have lived it already, and that world is waiting to be converted into scenes. If people were not writing books about people like me, I’d write one myself, spitting out all the painful things, rudely, lightly. Someone said to me, write your pleasure. I did.

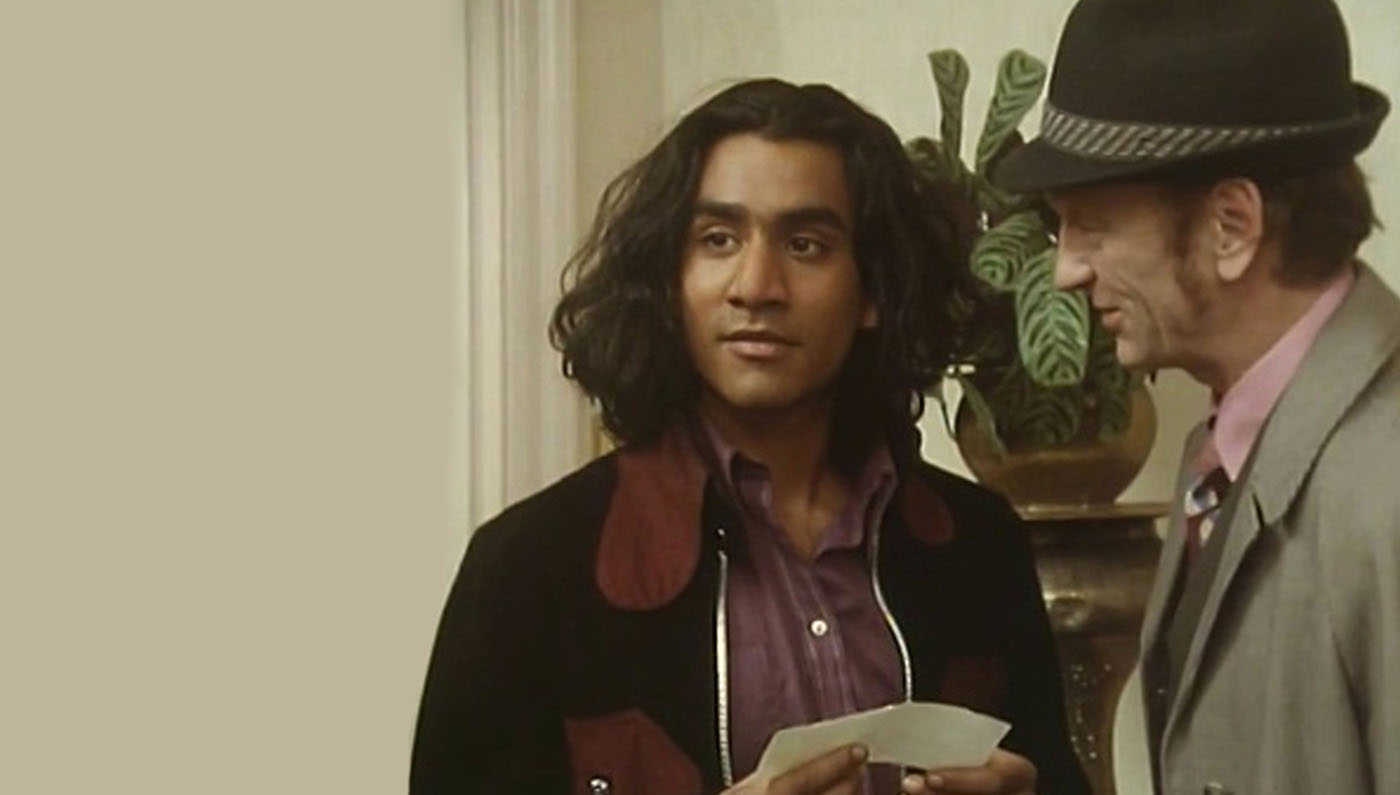

My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost. I am often considered to be a funny kind of Englishman, a new breed as it were, having emerged from two old histories. But I don’t care – Englishman I am (though not proud of it), from the South London suburbs and going somewhere. Perhaps it is the odd mixture of continents and blood, of here and there, of belonging and not, that makes me restless and easily bored. Or perhaps it was being brought up in the suburbs that did it. Anyway, why search the inner room when it’s enough to say that I was looking for trouble, any kind of movement, action and sexual interest I could find, because things were so gloomy, so slow and heavy, in our family, I don’t know why. Quite frankly, it was all getting me down and I was ready for anything.

Reading the first paragraph of The Buddha now, I’m surprised to notice that the hero, Karim Amir, announces his nationality three times. I guess he was insecure. Like David Bowie, he was eager to find an identity, throw it away, and start again the next day with another one, brand new.

In 2015, Zadie Smith wrote a lovely introduction to my novel. She describes discovering the book at school, which she calls a first for us “new breeds.” She says, “Irresponsibility is an essential element of comic writing.” And Karim Amir, my boy and avatar, who likes both boys and girls in bed, and where possible both at the same time, is determinedly wild and rash.

But Karim knows something that most people don’t know. And what he knows is priceless: that being a person of color isn’t at all like being white. No white person walks into a room and finds it weird that there are only white people present; no white person thinks of themselves as a problem for others, a question, a perplexity. No one asks them where they’re really from. Whites belong in the world. It’s theirs, they own it, and they don’t even appreciate it. But they do get defensive and cranky when you point it out, as you have to, repeatedly.

Karim understands that being a person of color means being bullied all the time. Yet while whites might consider themselves superior, it’s more original and enjoyable being underneath, laughing up at the poverty of privilege. Karim begins to get that his disadvantage is his advantage. Then he stops caring either way. He’s free.

Where does one write from? From one’s race, gender, age, political outlook? Or somewhere else? Sometimes people ask, and one asks oneself: what exactly are you doing when you’re doing it? This is an interesting question and not straightforward to answer. I guess one writes from a sort of void or gap; somewhere between consciousness and the unconscious. From where a bit of dream meets a bit of reality. From a shaded space where there isn’t too much control or criticism; from where things can just appear, if you’re lucky. From where hard work meets frivolity, and graft meets a giggle.

If anyone thanks me — and occasionally they do — for writing The Buddha, or says it meant something to them, I am always grateful, since I’m reminded of how a few decent people, along with some good stories, once got me out of a bit of a jam, and into a more open world.

As I think about my novel today, looking back on myself, I wish I were that boy again, free on his bike. But I know he’s still in me, funny, hopeful, rarin’ to go, always up for it, going somewhere.