The survivor of a shipwreck who has already lost everything, including his country, washes up along the coast of southern France, and starts a new life.

Jordan Elgrably

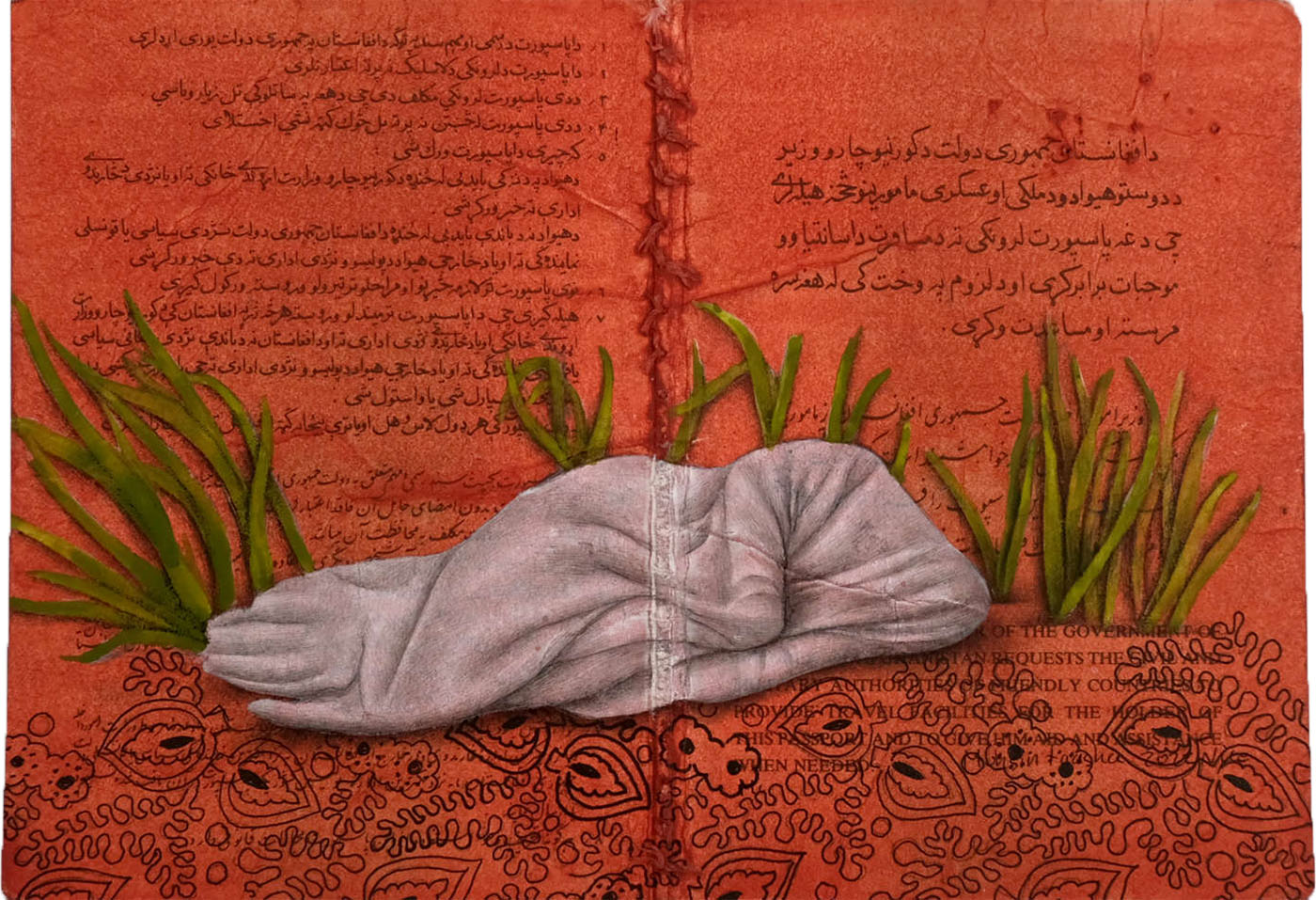

Thirty-eight clandestine migrants, including nineteen children, died one Saturday night when their vessel came apart off the coast of Italy near a seaside resort just outside Vintimille, where dozens of bodies were found strewn on a beach. Another eighty harragas on the same vessel survived when the gület, a Turkish wooden ship, hit the rocks in bad weather. The ship was smashed to splinters, and debris was found along 500 meters of Italian coastline, only a few kilometers from the border with France. Many of the survivors were from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, and there were migrants from Sudan and Somalia on board. Almost all the survivors were adults, while many of the missing and those found drowned on the beach were children. During triage, Italian authorities, aghast, lined up the little corpses but did not have enough body bags of the right size to go around.

The next day Tamim, a harrag and a lover of words and dogs, washed up dirty and disheveled on the beach a few kilometers from Narbonne, having survived the shipwreck that nearly cost him his life. The robust but shaken migrant, age thirty-five, was then lucky to find refuge in nearby Montpellier, where Afghans, Syrians, and migrants from Africa were able to gain a foothold.

A woman named Romy, with a tanned face and long exquisite fingers, working at the offices of SOS Méditerrannée, recorded his full name, date of birth, nationality, and other vitals. He spoke through an interpreter in a mix of Dari and English, while drinking chai that he nervously stopped to stir counterclockwise, as if he wished he could slow time or turn back the clock altogether.

Three weeks earlier he had crossed the border into Turkey in the back of a refrigerated meat truck, he and ten other men protected with nothing more than blankets and a determination to escape death sentences. From Kabul he had caught a ride hidden in the trunk of a family car that took him to Herat, and from there he’d found a bus that dropped him off in Isfahan. Another bus took him to the frontier with Iraq, and then there was the treacherous journey to Aleppo in which the truck he was riding took three sniper bullets before miraculously escaping into the night. It was in Aleppo that he found smugglers who sold Tamim the last space in the meat truck carrying them into Turkey. But before they reached the border between Azaz and Kilis, two of the Syrians boxed him into the corner of the truck farthest from the driver, one holding a knife to his gut and the other saying, in English, where is your money, give it to us, brother. At that very moment the truck must have hit a large pothole, because the three of them lurched backwards and Tamim threw his blanket over the Syrian with the knife and kicked him viciously in the head. The other man had rolled away to where two fellow Afghans took hold of him, but before any of them had long to consider what to do next, the truck stopped, the doors flew open, and they were all ordered out. From here you walk, imshi!

Romy recorded as much of his story as she could, and then asked: “Why are you applying for asylum?”

“You know, the Taliban took over the country and the Americans left, and during the chaos that ensued … they … killed my wife. They … killed my daughter … Women are no longer permitted to get an education, or even to work … I was a professor of literature at Kabul University, where I met my wife … her name is Rohina Rahimzai … there she met her end. They beat her to death with sticks in front of the library. You would like to know why? Yes, I want to know why, too. Do you think that they required a reason? Who would put those thugs and murderers on trial? Shall I tell you how my daughter Mojdeh, only six years old, perished? I am certain you would like to know, but I’m not prepared to talk about that now. I fled the country because people like me who ask questions, who ask too many questions, who aren’t necessarily good Muslims, who don’t revere the Qur’an above life itself, those of us readers … we are more likely to be killed than ordinary Afghans, who would prefer to live politely and quietly. Why France? Why have I come here? I washed up on your shores as a man who loves books and words and libraries and ideas. I thought by coming here, I could save myself.”

As much as he wanted to resume working as a literature professor, Tamim could not teach in Dari or Farsi in Montpellier, nor was his French more than rudimentary; but he spoke English well enough, with a pleasant accent that the French found easy to comprehend, and he was therefore able to make his way about the city. It wasn’t long before they found him a shelter and a bed, and from there he went to daily French classes along with other immigrants and refugees. During the evenings, he pored over a much-used copy of Norwegian writer Åsne Seierstad’s The Bookseller of Kabul, remembering that the subject of her story, Shah Muhammad Rais, had attempted to sue her for defamation, and lost.

Despite being a man absorbed by words and books in Dari, Farsi, and English, Tamim wasn’t beyond taking matters into his own hands — and, indeed, working with his hands. He informed Romy at SOS Méditerrannée that he was, in addition to his former university position, a man of all trades, a handyman with experience in carpentry, masonry, and many household projects that required speed and ingenuity. In other words, bricolage. She began to field him small jobs here and there, and after being in the city for only two full moons, he obtained a cheap cell phone. Soon afterwards he learned that he would be granted asylum, though the process would take much longer than even he could have predicted.

Maxime del Fiol, a client of his who had benefitted from Tamim’s handy use of carpentry tools and who was a monthly donor to SOS Méditerrannée, knew the propriétaire of a building in the city center only a short jaunt from the Préfecture, who had a studio apartment for rent.

Madame Gallimidi was a stout brunette in her retirement years. She sat the two men down in her large flat overlooking some of the oldest buildings in town. Finding Maxime and Tamim agreeable company, she served them Moroccan mint tea, and while beginning to slowly fill out the lease, she chattered about her late husband and how she had inherited his family’s apartment building, which had infuriated his two brothers and sister. While Madame Gallimidi regaled them with stories she had no doubt recounted a hundred times to anyone who would listen, Tamim looked about the flat, noticing the antique furniture that looked straight out of Madame Bovary, the Art Deco gilded mirror that ran from floor to ceiling, the shelves of old hardbound books, the musty smell of time and tobacco, and the bric-a-brac that revealed an eccentric’s penchant for collecting. Out of the corner of his eye, Tamim saw a white blur dash behind the sofa on which they were sitting. Madame Gallimidi perked up.

“Don’t mind him,” she said. “That’s just my dead husband, who’s come back to spy on me.” The large Persian poked his head out from behind the sofa, as if he understood that he was now the subject of conversation.

“Madame,” said Maxime, “I am going to be Tamim’s garant, as he’s new in our country and we have to support those who deserve asylum.”

The three of them signed the paperwork and Madame Gallimidi handed over a set of keys to her small, furnished studio on the top floor, which came with a mini-fridge, hotplate and microwave, for just 450 euros per month. Maxime wrote a check for the deposit, and the two of them thanked their host. Moments later, downstairs in the street, as Maxime was leaving, he said Tamim had a year to repay him.

About to part ways, Tamim thought of his dead wife and daughter and felt his heart tearing up his chest, but nonetheless experienced a spasmodic moment of joy and relief. Tamim was a six-foot man with coffee-colored skin and slightly Asian eyes, what Americans call “a person of color.” He wanted to seem strong but he could not stop his tears. “I can’t thank you enough, I’m in your debt. Don’t worry, I’ll repay you.”

Maxime fidgeted, uncomfortably put off by the man’s weeping, and finally blurted: “It’s nothing, nothing at all! You would do the same for me were the situation reversed, I know it.”

“I don’t know what I would do, because it’s hard to know who I am after all that I have experienced these last months, but I hope you are correct, Maxime, j’espère que vous avez raison … I would like to be a good person. I have not killed anyone, I was, after all, a literature professor and a writer, not a soldier; but after what they did to my family and my country, there are people I would like to kill. Yes, I would, and in fact—maybe I shouldn’t admit this to anyone—I often think about the ways I would like to strangle or stab or suffocate the men who took my family from me … I am sorry if I sound angry,” he said.

“Vengeance is in your heart,” Maxime replied. He paused for further consideration. “I can understand that you would think about it; it doesn’t make you crazy, or criminal. I would feel the same.” Maxime regarded his newly-minted friend and shook his hand sternly before rushing away down the cobblestoned street.

Tamim began to receive more and more calls on his new cellphone, which at first was a challenge, as all the callers began by speaking in French, but then switched to English, sometimes good English, and sometimes quite shaky and difficult to understand. After a while he had begun to build up a roster of regular clients who needed his handyman services, so he was often away from his flat during the day, working at jobs that had to be paid via a complex system organized between SOS Méditerrannée and the Préfecture; but at least it had the veneer of legality, and he did not fear deportation, which was the usual way migrants inhabited Montpellier — always wondering how long their idyll would last.

One day, Tamim noticed a beautiful dog that was stopping to sniff up people seated at the café where he was taking his morning coffee. He wondered about the breed, as the dog was of medium size with brindle coloring and light brown eyes. The animal was quite striking, reminding Tamim of a small lion in majesty and coloring. Tamim noticed that the dog had a collar, and he decided to call to the animal, which he did in a quiet voice. “Here, here,” he said, emitting a low whistle. The dog turned his head, scanned him for a moment, and then appeared to walk away, but then turned around and trotted back over and slowly approached him. “Hello, bonjour, what’s your name?” Tamim asked, holding out his bunched-up fist so the dog could smell him, which he did for a moment; then the animal licked the outside of his hand. Without any sudden movement, Tamim reached to examine the dog’s collar, and tried to read the tag on it. si vous me trouvez, c’est que je suis perdu ; appelez la SPA, 04 67 27 73 78.

How odd; whose dog was this? Tamim looked up the SPA on his phone and decided to take the dog to the shelter himself. He went inside the café and asked the barista for a piece of string or cord. The dog was still waiting at his table when he returned.

Later the following day, after it became evident that the dog had no owner, and careful to avoid his landlady and any of the other tenants in his building, Tamim brought his new companion home. The studio would be cramped for the two of them, but the building’s inner courtyard featured quite a large garden with trees, bushes, flowers, and a bench on which to idle away the day. He had already spent more than one afternoon sunning himself out there with The Bookseller of Kabul. Now, with the addition of the dog, which he decided to call “Ardeshir,” he would be spending much more time outdoors. He soon found himself taking Ardeshir for several daily walks around the neighborhood, which mainly comprised old stone buildings, and let him play in the garden. He also took him for long walks around the Promenade du Peyrou.

At first, as a new tenant, Tamim did his utmost to hide Ardeshir’s existence, as he had rented the studio as a quiet widower. Madame Gallimidi would likely not have been happy had he rented the place with an animal — a 30-kilo mixed-breed dog with a large head that could frighten almost anyone. But very quickly, people in the building took notice of Tamim walking his pet, and word soon drifted up to Madame, who lived on the third floor below his attic studio. She rapped at his door one morning, shortly after he had returned from walking Ardeshir around the neighborhood and down by La Panacée museum.

“Monsieur Ansary, you did not mention that you were the owner of a canine, but as a pet lover myself, I’m not going to let myself be upset with you.”

“Madame, I only rescued him ten days ago; I didn’t know of him at all when we signed the papers here, I promise you. He needed a home and a good daily meal. His name is Ardeshir, because he looks a bit like a lion…”

“Regardless, you should have consulted me. Now that this is a fait accompli, let me warn you to keep your dog away from my cat! You may not have noticed, but he is large and fearsome, and I daresay your boy would have his eyes scratched out if he tries anything funny, should they ever happen to meet. Try not to let that happen.”

Tamim felt grateful and relieved that he could keep his furry new friend, though he was surprised that Madame Gallimidi had made no remark about how on earth the two of them could possibly cohabitate such a constricted space, a single room of only 25 square meters. She couldn’t know that it was four times the size of the prison cell he had shared briefly in Kabul with eight other men, crammed in together for days with hardly anything to eat, and nothing but a hole in the concrete in which to do one’s business. The nearly airless cell carried a stench — the filth was beyond imagination — and they had had to take turns sleeping, twenty minutes apiece, while the others remained standing. By such standards, his Montpellier studio was a princely home; and besides, Ardeshir had been living on the street, and now the two were sheltered and warm.

One day after idling on the bench with a book, Tamim decided to venture out to the Monoprix to pick up some groceries, leaving his companion to wander the garden without him. The dog tried to follow him out into the courtyard, but he held up a palm to stop him. “You’ll be just fine here, Ardeshir, I’ll be back shortly. You stay … stay,” he said.

A short while later, bearing a bag packed with purchases, he let himself in to fetch the dog when he noticed Ardeshir tearing around the garden like a mad fiend. There was something black in his mouth, a large object that was a blur as he tore through the undergrowth and emerged from one bush only to vanish into another. Tamim whistled to the dog, and Ardeshir trotted out of a bush and cautiously approached. At last, he dropped the black object in front of Tamim, who could see with horror that it was a cat. The cat was not moving. Instinctively, he glanced up at Madame Gallimidi’s courtyard window, relieved that the lifeless animal wasn’t hers.

He struggled to get the dog, the cat, and the bag of groceries up the stairs. Once inside, he scolded Ardeshir and commanded him to sit: “You’re lucky we didn’t run into anyone on the stairs, you bad, horrible dog!” Tamim turned his attention to the cat’s corpse, and in that moment he realized that the animal was covered in black mud. Shaking his head, dreading the worst, he washed the cat off in the sink, and sure enough, its white fur was revealed. The cat was certainly dead, and must have belonged to Madame Gallimidi. He looked at Ardeshir as if to ask, why did you kill it? He remembered her quip about the cat being her dead husband returned to spy on her, and began to feel superstitious, as if he were being watched by the evil eye. This gnawed at him: he thought himself a modern man, a university-educated Afghan, not a person who would ever affix an amulet to his door or mutter preventive sayings to ward off maledictions.

Late that evening, shortly before midnight, noticing the moon was quite nearly full, Tamim stole down the stairs and deposited the dead Persian on the landlady’s welcome mat. The following morning he left shortly after dawn on a job, filled with fear that Ardeshir’s kill would cost him his asylum — or, at the very least, put him on the street.

That afternoon when he returned home, he noticed an ambulance pulling away from the apartment building. Two neighbors, a man and a woman whom he had previously acknowledged in the stairwell, were conversing in loud voices. “Bonjour,” Tamim said. “What’s going on?”

The man spoke and the woman shook her head sadly. “They’ve just taken Madame Gallimidi to the emergency room at Lapeyronie; she’s had a heart attack,” he said.

Tamim froze, as if he were paralyzed.

“The poor woman was going out to check the mail, but when she opened her door, she found her dead cat on the doorstep. Apparently, the cat had died three days ago, and her son had buried it for her in the garden.”

The woman from the first floor was shaking her head, and Tamim had no words. Reflexively, he glanced up at the lone window of his studio at the top of the building, angry with Ardeshir, but still unable to move. “Do you suppose she’ll be all right?” he said. The two neighbors bore sad, uncertain looks, and the woman shrugged as if to say that the old woman was doomed.

He found himself walking aimlessly around the quarter, unable to go home or decide on what to do next. After hours of wandering, Tamim found himself standing at the Louis Blanc tram stop and realized that he had to go visit Madame Gallimidi in the hospital. When he arrived at the Urgences, he was asked to produce his identification and carte vitale, but he said, in broken French: “I came to see Madame Gallimidi, she was brought here with a bad heart earlier. Please …”

“Are you a relative?” the woman behind the counter asked. Tamim shook his head. “I live in her building. Is there anyone else here to visit her, perhaps I could talk to them?”

The woman had no idea, and was of no further assistance. Tamim found a seat in the large waiting room and lost track of time, not knowing what he was doing there. After a while he realized that he could slip in past the guard desk when no one was nearby, and he wandered into the long, cold hallway, searching for Madame Gallimidi; but with four floors and kilometers of hallways and rooms, one after the other, he was unable to locate her. Several times, hospital personnel stopped to ask where he was going. Tamim failed to reply, and eventually a security man showed him the exit.

When he got home, he was a wreck, overcome with fatigue, weighed down by voices and ghosts. He had no idea whether Madame Gallimidi was alive or dead, nor whether he could be held responsible. The light seemed to dim, the walls were dark, and the dog lay quietly by the door, staring at Tamim with what appeared to be sad eyes. Without realizing what he was doing, Tamim kneeled down in front of Ardeshir and wrapped his hands around the animal’s throat, squeezing furiously, and the dog struggled for breath, kicking all four legs, eyes staring at his master’s darkened face as Tamim took the life out of him.

That very week, the Midi Libre reported that a thirty-seven-year-old man in the Tarn was being questioned about the death of his dog, a five-year-old Malinois that starved to death in his apartment just east of Albi. Placed under arrest, he was charged with “serious abuse and cruelty to a domestic animal.” He faces five years in prison and a fine of 75,000 euros.