Victory City, a novel by Salman Rushdie

Penguin Random House 2023

ISBN 9780593243398

Anis Shivani

Victory City, by Salman Rushdie, can be interpreted in at least three different ways: as a stand-alone imagined epic telling the story of the rise and fall of an empire (which I can say, unreservedly, works very well); as a creative reinterpretation of the actual history of the Vijayanagar Empire in South India (I do not have the information to pass judgment on whether this, an attempt at historical fiction, is successful); and finally, as a metacommentary on the writer’s own craft and his place in the world of practical compromise (here again it works exceedingly well, as a reflection of Rushdie’s growing maturity, which is even more in evidence than in his next-most-recent novel, Quichotte).

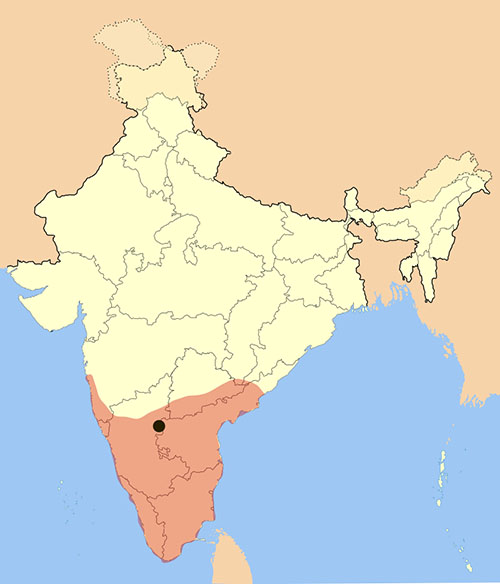

Although much more is known about the more famous dynasty to the north, the Mughals, who assumed center stage among India’s ruling dynasties at about the same time that the southern Vijayanagar Empire experienced a sudden collapse, enough is known about Vijayanagar (1365–1565) to fuel a great deal of speculation among scholars of both liberal and nationalist stripes, since it can be seen as one of the last great holdouts before Muslim rule dominated India for the next couple of centuries. V.S. Naipaul opens his India: A Wounded Civilization (1976) on the ruins of Hampi, the current location of the capital city, which was reduced to ash and rubble upon the empire’s calamitous final confrontation with the league of disparate Muslim dynasties in South India at the infamous Battle of Talikota. For Naipaul, the end of Vijayanagar (literally, Victory City) is a wound from which India has not yet recovered. The eminent contemporary historian of India, Richard M. Eaton, on the other hand, is careful to emphasize the points of convergence between the great Hindu and Muslim regimes in South India, which seems to me a more accurate representation of historical reality.

As a stand-alone novel, without reference to the actual Vijayanagar Empire whose story it retells in the form of the fictional Bisnaga Empire, Victory City does a fine job of imagining the ups and downs over two and a half centuries without the reader’s attention ever flagging. In fact, the final two parts of the four-part book, wherein the empire is making its own life and death decisions, are marked by increased momentum.

In the lead-up to those two final sections, the momentum remains both respectable and steady because the novel is framed in the form of a newly discovered manuscript, the lost epic poem Jayaparajaya, written by Pampa Kampana, heroine of the novel. She is given the power by a goddess to bring life into existence by the spreading of seeds, granted the long life of two and a half centuries (exactly coincident with the life of Vijayanagar), and the capacity, in disembodied form, to whisper enlightened thoughts of her choosing into the ears of the subjects and rulers of the Bisnaga Empire. To what extent this epic poem might correspond to the literary output of individual poets of the golden age of South Indian literature is something worth investigating, but as pure narrative, without reference to borrowings from existing literary classics, it packs a strong emotional punch, tied as it is to Pampa Kampana’s feminist awareness as well as that of the numerous generations of female descendants in whose destiny she involves herself during the course of her seemingly endless lifespan.

“Golden ages don’t last long,” as the narrator — the modern-day discoverer of Pampa Kampana’s manuscript — often asserts and as we all know, and much of the pleasure of the narrative qua narrative lies in the familiar arcs of aspiration, indulgence, arrogance, comeuppance, and sometimes redemption that afflict the various Vijayanagar dynasts. Rushdie’s interesting conceit is that the founders of the empire, Hukka and Bukka (in historical fact Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty), are cowherds blessed by Pampa Kampana with superior knowledge; they take the reins of an empire which emerges out of nowhere, from the sheer power of the seeds that sprout into people and animals and all things, and the intelligence that similarly comes into being ex nihilo from Pampa Kampana’s whisperings into people’s consciousnesses. In reality, Harihara and Bukka were probably generals in one of the dynasties rebelling against the then-declining Delhi Sultanate, not the hitherto obscure persons portrayed in the novel. There are useful and destructive advisors, helpful and unhelpful queens, wars galore with the surrounding Muslim kingdoms, all of it bound by Pampa Kampana’s initial optimism and eventual but very predictable disillusionment with the inability of ordinary humans to take advantage of the foresight available to them thanks to the goddess-inspired near-immortal among them. During a period of exile in the forest, when Pampa Kampana sends a parrot as a spy to the kingdom, this is what the parrot reports from the coronation speech of the new ruler proclaiming the ascendancy of literalness over inspiration:

From now on, […] Bisnaga will be ruled by faith, not magic. Magic has been queen here for too long. This city was not grown from magic seeds! You are not plants, to come from such vegetal origins! You all have memories, you know your life stories and the stories of those who came before you, your ancestors, who built the city before you were born. Those memories are genuine and were not implanted in your brain by any whispering sorceress. This is a place with a history. It is not the invention of a witch […] Henceforth our narrative, and our narrative only, will prevail, for it is the only true narrative. All false narratives will be suppressed. The narrative of Pampa Kampana is such a narrative, and it is full of wrong-headed ideas. It will be allowed no place in the history of the empire. Let us be clear. A woman’s place is not on the throne. It is, and will henceforth be, in the home.

Pampa Kampana’s very modern feminism is likewise mostly wasted on the people of Vijayanagar, eliciting no more than short bursts of enthusiasm. On the whole, her prescriptions for complete equality between men and women (she has no qualms about women taking over as rulers, for example) go ignored. The third part of the novel, which relates the glories and eventual downfall of the most successful of the historical Vijayanagar rulers, Krishnadevaraya (who authored the famous epic Amuktamalyada), coincides with the emotional maturation of Pampa Kampana, so that this last and most glorious golden age comes freighted with a particular sense of loss. It is refreshing to read about Pampa Kampana giving in to intimations of her own need to be accepted for her femininity and beauty, and just as heartbreaking to share in her agony when Krishnadevaraya blinds her in a fit of rage: “Forty more years would pass before the final collapse of Bisnaga, but its long, slow downfall began on the day of Krishnadevaraya’s wild, willful, terrible command, the day on which Saluva Timmarasu [the king’s leading advisor] and Pampa Kampana had their eyes put out by hot iron rods.”

In her last days, Pampa Kampana sets herself the task of setting down the chronicles of the empire with the help of young women of the ruling family who have taken on the mantle of her feminism. This makes for a perfect blending of story and rhythm when the streams of time merge toward the end and Pampa Kampana, at the palace in Bisnaga’s Victory City, recites — without being able to see them — the feverish developments in the final battle taking place a hundred miles away at Talikota.

There is much pleasure to be had in reading psychologically astute depictions of all the important personages in question, in prose that happens to be Rushdie’s most controlled yet, even more so than that deployed in the relatively subdued Quichotte. Here he is describing, in a matter-of-fact way, Pampa Kampana’s final sighting of one of her daughters, Zerelda, departing with her lover during the exile in the forest:

Pampa Kampana stayed up in the sky, hovering, watching Li Ye-He and Zerelda fly down to the hostelry where Cheng Ho habitually went for his spicy fish curry. One crow touched down on the ground and then Grandmaster Li stood there, with the other crow perched on his shoulder. After a brief pause, the grandmaster went indoors. Then time stopped for Pampa Kampana. For a timeless hour she sat on the roof of the inn listening to noises of revelry. Then the general’s party came out, singing lustily, and headed back to the ship. Then after a further timelessness there was the shadow of a man faintly visible in the prow of the ship in the darkness, with an even less visible black shadow sitting on his shoulder, looking up toward the invisible cheel in the midnight sky and raising a hand in farewell.

Now to the second, and more problematic, way of interpreting the novel, and my reasons for hesitation. In The Enchantress of Florence, Rushdie’s other novel about a medieval Victory City (this one Mughal emperor Akbar’s Fathpur Sikri, meaning “victory city located at Sikri”), we encounter an Akbar who is a superstitious, irrational, sex-crazed despot, when in reality the emperor was one of a handful of the most enlightened human beings who ever lived, as historians of every stripe universally acknowledge. Rushdie lists a much more extensive bibliography at the end of The Enchantress of Florence than he does here, one heavily weighted toward Florentine history, and mentions some historical sources, including Orientalist ones, for the Mughal part of the novel. Still, this does not explain why he would present Akbar in that highly unfavorable, and historically inaccurate, light. He also has the tendency to rely too much on the overstimulated imaginations of European travelers who wrote chronicles, making this the centerpiece in the Akbar novel, and allowing the historical Portuguese chroniclers much hypnotic sway over Pampa Kampana in this novel.

I have no sympathy for those who expect historical fiction to conform to every known bit of data, because historical fiction is most interesting when it deviates from the known facts, in big or small ways, to arrive at a creative synthesis which at its best can exceed the professional historian’s brief. The very point of historical fiction is to intervene creatively — yet persuasively — with a freedom the historian does not enjoy, thus letting us read history in a more illuminating way. But what is to be gained by presenting Akbar in such an historically inaccurate manner? It is this doubt stemming from his past practice that makes my reading of Victory City merely a tentative one until I can deeply consult my own sources on Vijayanagar history to see how the novel deviates from the historical record and to what purposes.

I can mention numerous examples that give me pause and necessitate a visit to the library if I am to arrive at an authoritative reading of the novel. But I’ll start by noting a couple of disconcerting generalities. I would have to go back to Rushdie’s previous novels to make sure, but my impression is that those works are disproportionately concerned with what we call the elites, and hardly ever with people in the lower social orders. This is certainly true of Victory City, where everyone other than members of the ruling classes appears as a bit player, part of an undifferentiated, unthinking mass. A certain asymmetrical history results when the point of view is the peculiar concerns of rulers. Secondly, despite mentioning David Gilmartin’s very helpful Beyond Turk and Hindu in the bibliography, and listing the astute Richard M. Eaton as well, the novel is too concerned with a sharp Hindu/Muslim divide as the key explanatory engine for the history of Vijayanagar, the proponents of the “one-godly” religion always at odds with those worshiping multiple gods. Religious identity, as scholarship on medieval India shows, simply wasn’t as clearly defined in that era; it was more of a subsequent creation on the part of the British colonialists. This means that the economy and material conditions are never a part of the story of Vijayanagar in the novel, even though they, more than personal foibles, would surely have explained most of the developments. This too leads to a highly distorted reading of history.

It also goes back to Rushdie’s lifelong troubles with religious orthodoxy. By making religion so central to the current reality of postcolonial peoples, in effect Western liberal scholarship reinforces such division, and also sidelines the role of political economy, which is more often than not the engine that drives unity or division. For example, those explaining the reaction to blasphemy in Islamic societies today in complete isolation from colonial exploitation, both past and present, make an unnatural fetish of it, and give it greater strength than it otherwise would have. Unfortunately, the same operation applies within the narrative of Victory City.

Specifically, I would raise these questions. Is Gangadevi, the historical poetess, part of the inspiration for Pampa Kampana? If so, to what extent does Pampa Kampana’s fictional Jayaparajaya concord with or deviate from the historical poet’s work? What was the reason to present the sage Vidyasagar — in the historical record the saint Vidyaranya — in highly negative terms, even as a physical abuser of the young Pampa Kampana (whom he gives the name Gangadevi), and as a person who manipulates religion for egoistic ends? Is that a deviation from history? Strangely enough, the novel achieves greater poignancy toward the end, when describing the glorious reign of Krishnadevaraya of the Tuluva dynasty, whose ecumenical tolerance is given prominence, and intuitively feels truer to history when compared to the depiction of Hukka and Bukka and their immediate progeny, who seem more susceptible to authorial manipulation. Is that because the historical record concerning early Vijayanagar is relatively lacking, or was there some other deeper authorial intention behind it? Most importantly, I would like to understand if the actual processes of cultural dynamism and ferment in Vijayanagar might have been overlooked altogether, by way of superimposition of contemporary liberal dogma, as was the case with the Akbar novel. I simply don’t know.

Finally, when it comes to interpreting the novel as the lifelong maturation of a writer, the novel again becomes a pleasure to read in and of itself, without regard to correspondence with the historical record. Quichotte’s theme of the writer being burdened by an intuition about the future greater than others around him continues to a poignant degree in Victory City. The writer does not age, and when he does, it occurs as even more of a calamity than for ordinary mortals. The writer is self-creator, the author of a reality greater than himself, which is certainly true of Rushdie’s biography as a writer in the world, but is true in general as well. The writer is both eminently erasable (as when Pampa Kampana has to bury her epic in a pot in the ruined city and leaves it to chance for her great work to be discovered by posterity) and permanently inerasable simply because of his or her influence on the material reality when alive.

Victory City was presumably completed before the shocking attack on Rushdie in Chautauqua, New York, in the summer of 2022, as a result of which he tragically lost an eye. Consider, again, the blinding of Pampa Kampana, another author ahead of her time, and her recollection of this frightening event, in light of what actually happened to Rushdie:

In [her dreams] she saw again the blacksmith’s guilty face, the iron rod lowered into the furnace, and removed with its tip red-hot. She felt Ulupi Junior behind her, holding her arms, and Thimma the Huge towering over her, holding her head still. She watched the approach of the rod, felt its heat; then she woke up, shaking, sweating her lost eyesight out of every pore of her body.

Rushdie is at his best in this novel and in his writing in general when he allows such vulnerability to come through.