The war on Gaza and Hamas reminds a Palestinian American poet of her father and stories of home and immigration.

Deema K. Shehabi

“You’ve come so far habibti, but there’s no shame in turning back,” my father said, smiling, handsome in a white shirt, his arm swirling around my shoulders. On that fateful day, I sat, fanned out on the university lawn, the gruff hooting from fraternities louder than birdsong, reflecting on how my life in America would change.

In his haunting and elegiac memoir, House of Stone, journalist Anthony Shadid recounts an origin myth of the people from Marjayoun, a small village in southern Lebanon. In the story, the founding members of the village become lost and indecisive, and they ask their leader whether to leave their homes, which have become ridden with strife and anguish. In response, their leader brings forth three birds; he plucks the feathers of the first and clips the wings of the second, while the third he lets be. The third one, the whole bird, then flies home to Marjayoun, the foreshadowed home — a requiem of home with poppies and lemon trees.

As I watch my family scramble for safety in Gaza, I think of my father, who was one of my first teachers and whose life instructions I seek in times of distress. He passed away seven years ago, and his death not only left me with a sense of disjunction and absence but also with the sense that my history, my story, and my renaissance as a daughter, both young and middle-aged (a self who had been inextricably tied to his on a buoyant soul level), had drifted to an end — but almost like a question that reverts to its beginning. Two months before his death, I saw my father in Beirut, his adopted city for the latter years of his life. I left him knowing it might have been our final time together, but the truth is daughters can be gullible; the perceived invincibility of their fathers is both shield and shard.

There’s no shame in turning back. I paddle often back to that place: a magnanimous mother leaning her small frame on the apartment balcony in Kuwait, waving her hand in circular motions, and reciting Ayat el-Kursi to my traveling father. Turning back was the hush of long siesta afternoons and the hum of air conditioning outside my bedroom window, which mingled with my inchoate writerly dreams. Charlotte Bronte’s protagonist Jane Eyre and her sermon on love and its discontents had a marked (indeed burning) effect on my soul as a young teen, as did Lebanese singer Fairuz’s voice with its velvety, gauzy texture. The call to prayer at dawn and its repetition throughout the day grounded me and gave me some minutes’ respite from schoolwork, incessant teen gossip, and social visits. In the evenings, as the searing heat yielded to a certain softness in the air, I would fling open my bedroom window and listen to sea sounds: always in the eucalyptus trees across the street and along the stucco wall below my window. Sometimes, depending on the wind’s direction, the smell of iodine filled my nostrils and provoked both a simultaneous feeling of placement and displacement engendered by an intuitive understanding of the sea’s rhythmic restlessness.

When I turned 12, I stood with my mother at a candlelight vigil in downtown Kuwait grieving the women, children, and men who had died in the Sabra and Chatila massacre in Lebanon. When I turned around to hold my mother’s hand, her face blew a hole into my heart. Later that evening, I braided photos of the dead children into my hair and left them there until they fell out; nothing wafts sickness like the smell of massacre that reeks of home. Before morning, I had rescinded my childhood, becoming an artisan of loss.

When my mother died, my father did not wither. He erupted, suddenly polished by grief into a long-listening father. He became my closest friend. During the first Gulf War, I lost contact with him for three months. Later, when he stepped out of an airplane on a Parisian tarmac as part of Jesse Jackson’s rescue mission, I immediately recognized his smile as he turned towards the camera, handsome in a white shirt.

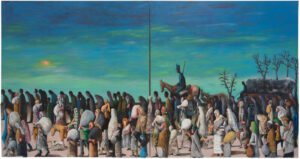

In college, I wasted time at the dinky and poorly lit Café Algiers in Cambridge, Massachusetts, pouring over the news of the day with friends, affirming our moral stances, thinking we could stop the wars always brewing in the pleated distance. These were happy years, but they were often punctuated by tearful TV viewing as America launched its “shock and awe” campaign against Iraq. From CNN’s newsroom emerged a language cleansed of limbs and gore, projected against a panoramic image of an electrified sky. By the time all Gulf wars were “over,” (wars that have only multiplied since I was nineteen), a million Iraqis had perished. In 2020, an immensely powerful explosion erupted in Beirut. Refugees from the Syrian war now number 13.5 million. Today, Palestinians are experiencing genocide in front of the camera’s eye. Are those the birds shorn of feathers, torn by war and displacement? On the news, I am continuously assaulted: a splotch of blood on the pavement signals the vanished fields of childhood. One poet says to another that our task is Sisyphean in the United States. In my poems, I lament the distance between me and my people, evoking Lorca:

Angels with daggers march through the funereal air of burned children, and you’re in the witness seat when the balcony opens.

I want to watch those voluptuous watermelons prune the ash,

says one angel, so for God’s sake keep clear when the balcony opens.

My story in America is not your traditional immigrant story of hardships, of fleeing from oppression, or of sacrifice for a new generation. Rather, it’s about echoes of conversations whispered to us by our loved ones that we hear over and over. What would have happened had I turned back? The poet Eavan Boland writes that “every step towards an origin is also an advance towards a silence.” What she meant was the silence of a quotidian life, where women were divorced from language and poetry and subsequently erased from a communal and national history in Ireland. But, as an exilic poet myself, I took her words and pondered: what if “every step towards an origin” was also a flowering — loud and unadulterated?

This question pierces me whenever I return to the Arab world. As I sat beneath the banyan trees (unhinged by the sight of their strangler trunks) in the middle of Beirut, I knew I was erased from a history that was mine in a specific time and place, and that was the real fracture.

I also experience fracture in America, and I struggle from my place at the margins, trying to knock down the corridors of power while perpetually seeking to enter the mainstream. From school, my son texts me, asking about a lesson being presented by his government teacher. Is it accurate or biased? Too exhausted to answer, I explain to him that the beauty of our people and the complex, irreducible, non-commodified tapestries of our relationships are omitted from the story of who we are in the West. This existence in opposition (the endless negations, no this is not who we are) reminds me of one of the birds in Anthony Shadid’s story, the one with clipped wings.

When I returned to Beirut after my father’s death, I could hear his voice everywhere, above the syntax of supplications rising like smoke during the funeral, above the Palestine sunbirds that upraised twilight over the mountains. When we placed him in the moist soil, I looked up but couldn’t bear the sight of the old pines with their branches hanging heavily in the cemetery named after two fighters who hid there during the Civil War, or the refugee children with death’s punctuality in their eyes skipping barefoot over white marble slabs. Their business was to clean graves and offer words, moths that break windows at night: may you live long in his place.

My young cousin in Gaza beseeches the world, how could you do this to us, how could you let them, how could this happen? She posts about the massacre at Al Ahli Hospital and tells the viewer that she’s not sorry for showing these images. An artist creates a rendering of the massacred children, depicting them as little angels with wings, whole birds flying above the gore to their foreshadowed home. My uncle, who sings Frank Sinatra to me across phone lines and distances, sits in a sunlit room in the lull between bombings and sends voice notes: “We are here, we are fine, our faith in God is strong, and remember, we live in you.”

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

Love you and your artist heart. Praying for peace against the odds it seems. Jon Palley

Such beautiful, tender, poignant, intimate snapshots of the broken world.

Thank you for writing, Deema. I learned about the Sabra and Shatila massacre today. Heartbreaking. “We live in you” invokes both tenderness and responsibility, which I know you bear. May a ceasefire come soon to end this suffering!

this is so beautiful Deema…thank you. Sending you love and solidarity

Jazaki Allahu Khair. Sometimes the artist, the writer, the poet, can bridge the gap between those who understand and those who do not. It is your truthful expression that is so relatable to those who are human. Sending heartfelt dua for you, your family, the Martyrs, the oppressed, Palestinians, and the believers everywhere.