A native Moroccan’s quest for an intersectional indigeneity.

One cannot defend Amazigh rights to land, language, and culture in their homeland and, in the meantime, be blind to other indigenous peoples’ struggle for similar rights, albeit in dissimilar colonialist contexts.

Brahim El Guabli

I speak Tamazight. It is my mother tongue. A language that has been both within and out of reach. Both close and distant. Both intimate and elusive. Tamazight has always been available to me at home and in familial settings, but it was never part of my academic or intellectual instruction. In my childhood, Tamazight, this mother tongue, was everywhere and nowhere. It helped me make sense of my immediate world, but it was never allowed to function as an ordinary language through which I or my generation understood the larger world.

This presence-absence of the mother tongue haunts me every day and complicates my relationship to other languages. It pushes me to wonder how the way I relate to the world would have been different had I been given the opportunity to learn about it through my thwarted mother language. I recently learned, while reading a book, that, unbeknownst to me and to other speakers of Tamazight, we speak a “patched” language; a language made of leftovers of other, stand-alone languages.

Should we believe this allegation, the language I have spoken and taken for granted as a mother tongue my entire life is nothing but a borrowed tongue; an impure and inauthentic tongue in that. However, unlike any other language I speak, my mother tongue is mine. I am not its guest. I am rather its inhabitant. It is my home, my roof, my shelter, and my go-to place whenever my host languages break down and become too narrow to contain my thoughts. My mother tongue is not just the foundation on which my other tongues rest; it is rather the flame whose incandescence fuels the ability of my host tongues to express themselves.

Mahjoubi Aherdan, the founder of the Popular Movement Party and a pioneer champion of Amazigh cultural and linguistic rights in Morocco, reports a conversation that happened between him and Mohammed El Fassi in the presence of King Hassan II in the first years of his accession to the throne. According to Aherdan, El Fassi, who was a former Minister of Culture, was sitting next to him during a Ramadan iftar in the royal place in Fes and asked him in Tamazight to pass around the pot of harira, a national stew in Morocco. Aherdan refused to serve El Fassi, explaining to him that this was due to him “proclaiming that Tamazight is not a language and that there was no need to foreground its contribution to our civilization.”[1] King Hassan II heard the two men’s argument and intervened to put an end to it. He assured them that Tamazight was a national issue that the state would take on in twenty years, once national unity was consolidated.

The saying “kam ḥajatan qaḍaynāhā bi-tarkiha” (inaction may reap great benefits), meaning that one may achieve great gain by doing nothing, applies here. For a long time, inaction was the way my mother tongue was forced out of public life, including in the media and school curricula. “Chronocracy,” which I use here to mean the use of time as a mode of governmentality to wear people and their causes out, worked efficiently as a way to defer the resolution of Amazigh demands for decades. However, when al-jami‘iyya al-maghribiyya li-al-baḥt wa-al-tabādul al-thaqāfī (The Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange, AMREC) charted the path for the advent of the Amazigh Cultural Movement (ACM) in 1967, Imazighen regained control of their time. Time has been on Tamazight’s side since then, and Imazighen have since inscribed their demands in their own temporality. Although Aherdan’s story belongs to a different time, its lessons show that those who refuse to live in the present are condemned to dwell in the past.

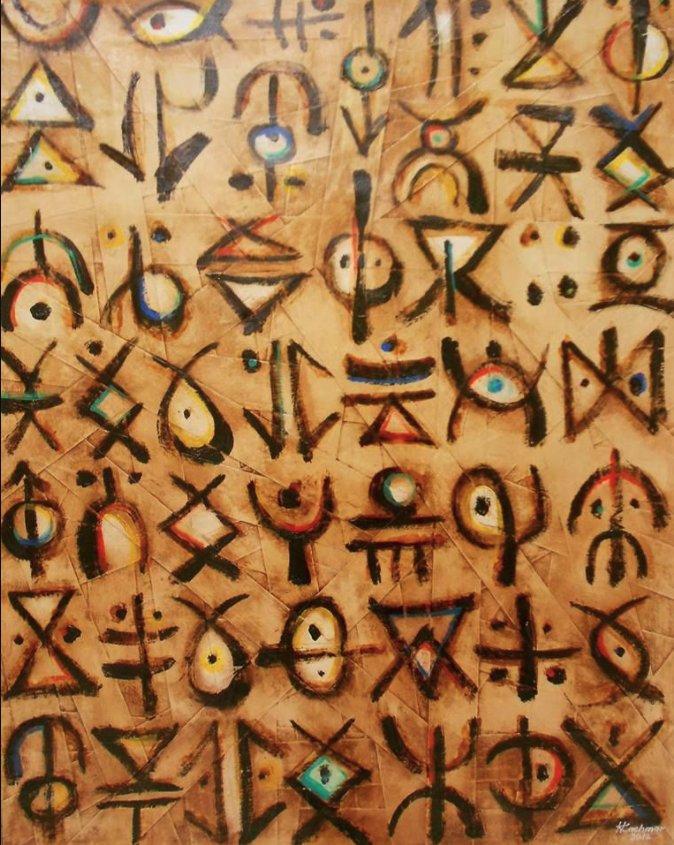

In his defense, El Fassi told Aherdan a joke that he had supposedly heard from an Amazigh learned person while in French jail in Errachidia in the 1950s. The joke said that when languages were first created, Imazighen, the indigenous people of Tamazgha, were not given a language. Only after they protested did the language distributor pull bits and pieces from different already-existing languages to make up Tamazight. As such, Tamazight is not an original language, but rather a patchwork of tongues. The joke is a literal translation of the verb بَرْبَرَ (barbara), which means to blubber or burble. Subverting the negationist intentions underlying his interlocutor’s joke, Aherdan replied to El Fassi that what he had just said “was proof of the universality of Berber language.”[2]—a point that I will discuss later. However, unlike Aherdan, I would insist on the fact that this violent joke inadvertently places agency of the right to a language with Imazighen. The intent of the joke was to strip Tamazight of its quality as a language, but when we flip it over on its head, it reveals Imazighen’s ardent desire to have their language. Hence, Tamazight was not a gift; it is an act of will. A language created for a people who demanded to have a language of their own.

Musing with Aherdan’s curious response to his interlocutor, I venture to say that he placed Tamazight in the pre-Babelian moment of universal communication. To borrow philosopher Abdeslam Benabdelali’s words in the context of translation, Aherdan, probably without knowing, engaged in a productive “mutiny” by positioning Tamazight as “an original language.”[3] This pre-Babelian time was the period that preceded the disintegration of Babel. It was a time of unbounded intelligibility. In accepting the misguided patchiness of our language, we are able to affirm its all-embracing potential and endeavor to relive through it a time that predated the creation of languages.

Historically, there is no colonialism that did not attempt to erase local languages.

As an indigenous Tamazghan, meaning from Tamazgha, the Amazigh homeland, I speak, read, and write, and exist in a language that preceded Babel, allowing me to seek a better universal. Each time I open my mouth, I am aware that I pronounce the words of a residual language, a remnant of the pre-Babelian entente.

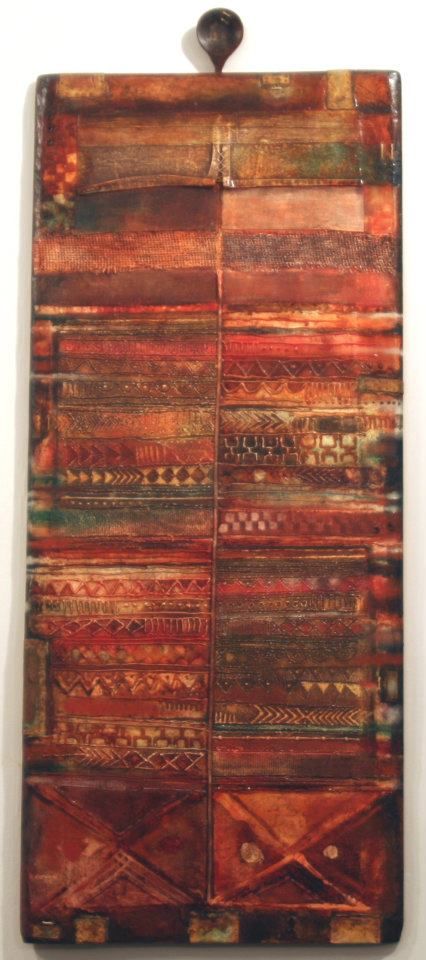

While other languages were born for specific nations, Tamazight, this obdurate language that refuses to vanish or dissolve despite myriad colonialisms and aggressive, exclusive language policies, is, by the various circumstances of its imagined birth, an inclusive, mothering language. A mothering language that has the capacity to open its registers for other words, structures, turns of phrase, and modes of existence that self-sufficient, Babelian languages may not welcome. The history of colonialism in Tamazgha and the different empires that dominated the region without ever erasing Imazighen or their language is edifying in this regard. Millions of farmers throughout Morocco use igger (field) and asnus (donkey),[4] two important words related to farming, without ever knowing that their roots reach deeply into Latin. Likewise, words, like rrestora (restaurant) and scuela (school), have been Amazighized, and most recently one can hear tran (train) without even paying any attention to their foreign origins. Luckily, Tamazight has not as of yet developed a police of language purity; we do not need one. A living language should remain a convivial, ecumenical home where other tongues can intermingle and cross-fertilize each other. This is also the way to differentiate a mothering, indigenous tongue from a colonizing, phagocyte language.

All colonialisms target indigenous languages. Unlike what we might assume, dispossession does not start with the expropriation of land or property. It starts with language and toponymy. Language is a tool for both liberation and domination, and colonialisms thrive on persuading indigenous people that their languages are worthless. Toponymy is what inscribes people and their language in place, and its erasure undermines language. The tendency to deny the existence of Tamazight as a language is now obsolete, but old habits die hard and one still sees its remnants here and there in social media. Several decades ago, Abdelkébir Khatibi wrote sarcastically about this situation in saying that “We, Maghrebis, have taken fourteen centuries to learn Arabic (more or less), more than a century to learn French (more or less); but we have not, since time immemorial, been able to write Berber.”[5]

There is much that can be critiqued in Khatibi’s statement, but I particularly want to highlight his forthright assessment of the fact that Tamazight was marginalized in its homeland compared to French and Arabic. Simply put, language policy makers were never convinced that Tamazight was a language in the first place. But as we say in Tamazight “ⵓⵔ ⵉⵙⵙⵉⵏ ⵎⴰ ⵉⵍⵍⴰⵏ ⵖ ⵓⵡⵍⴽ ⴱⵍⴰ ⵡⴰⴷⴰ ⵉⵙ ⵉⵜⵜⵓⵜⵏ/ur issin mayllan gh uwlk bla wada iss ittutn,” meaning that only those who are affected understand the hurt of affliction. The pain of negation of one’s language cannot be felt by decision-makers. Yet, our language is what allows us to make sense of the world and anchor our subjectivity in the firm ground of our lived reality. Moreover, without language we can neither convey our will nor express our pain. Disinheritance and dispossession are inherently painful, and denying indigenous people access to their language robs them of their right to articulating their pain. Amnesia does not just threaten indigenous people’s languages but also the very possibility of them giving a name to their traumas.

Historically, there is no colonialism that did not attempt to erase local languages. Disappeared Amazigh academic and intellectual Boujemâa Hebaz, one of the pioneers of AMREC in the 1960s, clearly articulated this equation in his discussion of French colonialism’s search to suppress the possibility of resistance by undermining both Tamazight and Arabic.[6] A Black scholar, who bridged the gap between Amazighitude and Négritude at a time when these questions were not yet broached in Moroccan society, Hebaz weeded race awareness with a precocious decolonial consciousness to link societal liberation to the rehabilitation to Tamazight. We now know for sure that mother tongues are the first bulwark against dispossession.

I remember times when I was asked to speak Arabic or French because Berber was not classy enough, but I insisted on speaking my language any way.

Gaining awareness of these processes is neither intuitive nor immediately conceivable. It is rather the culmination of Amazighitude (al-’amāzīghānīyya) by which I mean a process that allows us to gain consciousness of our Amazigh indigeneity and work to restore our critical, decolonized self. Amazighitude opens our eyes to our situation as subaltern subjects who, similarly to other indigenous people in other parts of the world, underwent myriad forms of linguistic and cultural expropriation. Amazighitude puts us on par with other indigenous peoples whose languages, lands, and cultures were subjected to the violence inherent to domination.

My own path toward Amazighitude has been made through resistance to deculturation. It was not difficult to be aware of your difference when everyone around you imitated the Amazigh accent or made fun of Imazighen. Identity lines are demarcated by the language one speaks, and boundaries of difference are made even clearer by one’s Amazighity. I remember times when I was asked to speak Arabic or French because Berber was not classy enough, but I insisted on speaking my language any way. At home in the United States, where I live, I speak Tamazight with my children, making Amazighitude a daily practice to instill in them pride in their “father tongue”.

Amazighitude is not just the active rejection of the normalization of bias. It is also a permanent endeavor to correct incorrect views, push back against prejudice, and assert our identity even when we are reluctant to do so. Amazighitude is a proactive position in the world and a constant preoccupation with the wrongs done to indigenous peoples; not just in Tamazgha but globally. This leads naturally to Amazighitude being a space for the coalescence of Amazigh indigeneity with other indigeneities against alienation and expropriation.

My Amazighitude — this consciousness of my rootedness in the world as an Amazigh person whose subjectivity is underlain by layers of relationships to language, land, and people — has allowed to me to reorient my intellectual energy toward thinking in and through Tamazight. As a result of this reorientation, I am now able to spend more time to comprehend what it means to think and rationalize the world in intellectual terms through my mother tongue.[7] For a long time I sought refuge in other languages, but achieving Amazighitude is the culmination of my journey toward the rehabilitation of the tongue that should have been the medium of my primary education in the first place. As I am engaged in this process, I recently realized that the act of thinking in Tamazight is expressed by the verb “swingm,” which means thinking pensively and anxiously. The philosophical notion of angoisse intellectuelle is already ingrained in the Amazigh verb. I wonder why Imazighen have associated thinking with anxiety. Is it related to the ontological experience of exclusion or is it merely due to their ability to capture the mental effort involved in thinking? I have no answer, but I continue to explore this question in relation to tilit (being/subjectivity) and tamagit (identity). Every speaker of Tamazight knows that bīyswingimn is the one who is consumed by thinking. As I continue my iswingimn (the plural of thinking) in Tamazight, I am amazed by the link that the language establishes between the formation of the Amazigh tilit and tamagit and their grounding in an immemorial anxiety that inscribes an indigenous reality and lived experience in the verb used to describe the act of thinking.

Like every indigenous liberation ideology, Amazighitude requires an ethical position vis-à-vis the just causes of other people in the world. Indigeneity, both as a paradigm and as a practice, is grounded in a decolonial mindset. Dei and Jaimungal have persuasively argued that “the assertion of Indigeneity is a politicized form of intellectual resistance,”[8] staking out the path for an uncompromising position toward colonialisms. One cannot defend Amazigh rights to land, language, and culture in their homeland and, in the meantime, be blind to other indigenous peoples’ struggle for similar rights, albeit in dissimilar colonialist contexts. Amazighitude is, therefore, a multiply critical attitude that looks both within and without. The critique of the internal marginalization of Tamazight within its homeland should coalesce with a refined knowledge about and support of other indigenous people who face injustice. Amazighitude requires a larger framework of analysis to connect local struggles to global movements that seek to make the world a better place for those who are excluded based on language, gender, indigeneity, race, or class.

In inscribing Amazighitude in larger human concerns, we are able to place Amazigh indigeneity in its rightful place within the global and intersectional solidarities between indigenous peoples across the globe. Hence, the one who achieves Amazighitude has the duty to stand in solidarity with those who are treated inequitably in their ancestral homelands regardless of who and where they are. Indigeneity cannot be a vehicle for condoning colonialism in any way. And so, Amazighitude is inscribed in progressive politics.

In the eyes of the Amazigh Cultural Movement, a truly global and democratic Moroccan culture ‘should take into account all its constitutive elements, including Amazighity, Arabness, and Africanness’ in their interaction with human and Islamic civilization.

The seeds of this progressive attitude can be found in the earliest conceptualizations of the Amazigh Cultural Movement, and in its struggle for the recognition of Imazighen’s cultural and linguistic rights. While the joke I started with was an example of what we can call al-waḥda fī al-iqṣā’ (unity in exclusion), which cannot accommodate difference, the pioneers of the ACM developed “al-waḥda fī al-tanawwu‘” (unity in the diversity) as a motto for their movement. The difference between the two visions for unity cannot be bridged. Unity in exclusion required Imazighen to accept amnesia and assimilation as a foundation for nation-building in the post-colonial period, whereas “unity in diversity” embraced difference as the corner stone of the national identity to be forged after independence. Even at the worst moments when its conferences were banned and its meetings were cancelled, the ACM held firmly to this principle, which envisioned Amazighity and Arabness as allies in the struggle for democratization. In the eyes of the ACM, a truly global and democratic Moroccan culture “should take into account all its constitutive elements, including Amazighity, Arabness, and Africanness” in their interaction with human and Islamic civilization.[9] Anyone who knows the literature of the ACM pioneers would notice that they championed a compellingly inclusive vision of the nation. This inclusive approach saw Imazighen as hosts in their homeland whereas the exclusionists wanted to treat them like guests. We all know the difference between hosts and guests in terms of authority and expectations.

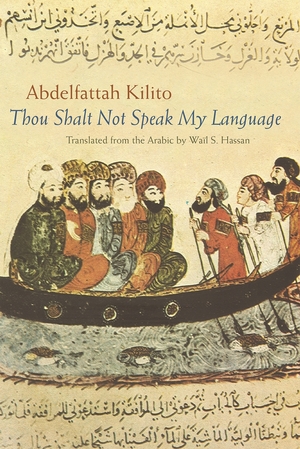

Abdelfattah Kilito argues that we are all guests of language. Kilito demonstrates how the languages we learn take possession of us, haunt us, making us hosts of language.[10] Guests of any kind are expected to adhere to strict codes of conduct. The Arabic word adab, which means both manners and literature,[11] enunciates the inhibitions that accompany guest-hood. I, however, would like to take issue with this guest-hood in language. Mohammed Khair-Eddine, the foremost Amazigh novelist writing in French, would not have brutalized and jolted French from within in his oeuvre had he abided by the rules of hospitality. However, because he ran roughshod over the rules of hospitality, Khair-Eddine managed to “explode” the Amazigh tilit and tamagit from within the Francophone text. I imagine Khair-Eddine repeating to himself that “ⴹⴹⵉⴼ ⵓⵔⴰ ⵉⵛⵕⴰⴹ/ḍḍif ura ishrāḍ” (guests can’t be choosers) does not apply to anyone, like himself, who turns disobedience into creativity and insolence into a statement on a broken world. One has to be an ill-mannered guest in any given language to tap into its unexplored vistas. Hence, one has to strive to be an undesirable guest, a persona non grata in the foreign tongue, to free oneself of this status of being a permanent guest in language. This leads me to wonder about being a guest in one’s mother tongue.

In our mother tongues, we are hosts. Being a host means that you are the one who sets expectations. The most obvious advantage to being a host is that you do not have to live with the anxiety of incorrect grammar or mispronunciation. After all, one is within their own language and even if they err their error cannot be attributed to ignorance. How often do we catch ourselves making silly mistakes in foreign languages and hope that our listeners would not judge us based on them? It is easier to be ignorant in one’s mother tongue than even slightly underperform in a foreign language.

Raissa Kelly sings a version of Busālm, a famous song from the Amazigh repertoire.

For indigenous people who never had a chance to be educated in their mother tongue, anxiety in foreign languages is the result of an exilic condition from a language that they know had stopped at the moment they entered the school system. Fear and anxiety hark back to that violent weaning off from the mother tongue at school age. Also, because Tamazight remained mostly oral, opportunities to be a host have been very rare. This is probably the explanation of the generosity Imazighen display toward those who learn their language.[12] I remember how a francophone woman named Raissa Kelly became a sensational figure in Amazigh homes in 1990s.[13] Singing in Tashlḥīt, Kelly reversed the usual trajectory of language learning in post-colonial Morocco and became a star in every Amazigh home that had a VCD or a DVD player in the 1990s. By that time, it had already been forty years since direct colonialism had ended and most Imazighen had no idea that their language was once upon a time spoken by many colonial administrators, but Raissa Kelly was a phenomenal occurrence, and her adventure into our language was met with a lot of hospitality. Kelly disappeared from the scene since the passing of Hassan Aglaou, her musical partner, over two decades ago. Yet, now, more than twenty years later, I still wonder if Kelly was a host or guest or possibly both.

States and societies in Tamazgha are changing fast, living more or less on Amazigh time. Schools, media outlets, the public sphere, institutions of higher learning, and the cultural scene have been re-Amazighized. One may not be happy with the pace of these transformations, but the naked eye cannot deny the phenomenal changes that Amazighitude brought to the erstwhile exclusive conception of national identity in the region. Culture has been the locus in which Amazighitude flourished the most.

Alas, these profound changes have not been accompanied by changes in academic departments that focus on the study of the Middle East and North Africa. Academia can manifest its Amazighitude by engaging in proactive endeavors to rehabilitate Amazigh language, culture, and literature in current curriculums. Amazighitude will become an academic reality when departmental setups are revised to treat Tamazight and its cultural production equitably with Arabic and French and invest in the necessary human resources for its full inclusion as a requirement for majors. Tamazight will then cease to be an ephemeral guest in academic works and course offerings about Tamazgha, and Amazighitude will be a normalized way to approach Amazigh indigeneity in connection to other indigeneities.

Notes

[1] I read a version of this story in Arabic in an interview Aherdan gave to the daily al-Aḥdāth al-maghribīyya in 2001 . However, I also discovered that Driss Basri, the former powerful Minister of Interior, reported it in his book Le Maroc des potentialités: Génie d’un roi et d’un people (Rabat: Royaume du Maroc, Ministère de l’Information, 1989), 276-280.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Abdeslam Benabdelali. Fī al-tarjama (Rabat : Dār Tubqāl lil-al-Nashr, 2006), 74.

[4]See “Mots latins ou supposés latins en berbère,” [http://zighcult.canalblog.com/archives/2006/05/14/1810193.html], does this work?] (accessed May 25, 2022).

[5] Abdelkbir Khatibi. Maghreb pluriel (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1973), 179.

[6] Boujemâa Hebaz, “L’aspect en berbère tachelhiyt (Maroc), parler de base, Imini (Marrakech-Ouarzazate),” PhD diss., (Université Paris 5 René Descartes, 1979), 5.

[7] In his opening remarks during the “Fourth Session of the Agadir Summer School” in 1991, Brahim Akhiyyat, AMREC’s founding president, called on Amazigh scholars to “revisit their treatment of [Amazigh] literary texts both in terms of the terminology and the criteria used to evaluate the quality of the [literary] output in order to redress the path of the Amazigh literary movement.” This prescient interpellation reveals the need for thought from within the language itself to generate an Amazigh metalanguage. See Brahim Akhiyyat, “Kalimat raīs al-lajna al-munẓẓima,” in Jam‘iyyat al-jāmi ‘a al-ạyfīyya bi-agādīr. Al-Taqāfa al-’amāzīghīyya bayna al-taqlīd wa-alḥadātha (Rabat : Imprimerie El Maarif Al Jadida, 1996), 21.

[8] George J. Sefa Dei and Cristina Sherry Jaimungal, “Indigeneity and Decolonial Resistance: An Introduction,” in Dei, George J. Sefa, and Jaimungal, Cristina, eds. Indigeneity and Decolonial Resistance : Alternatives to Colonial Thinking and Practice (Bloomfield: Myers Education Press, 2018), 2.

[9] Lahcen Kahmou, “al-kalima al-iftitāḥīyya,” in Jam‘iyyat al-jāmi ‘a al-ạyfīyya bi-agādīr. Al-Taqāfa al-’amāzīghīyya bayna al-taqlīd wa-alḥadātha (Rabat : Imprimerie El Maarif Al Jadida, 1996), 15.

[10] Abdelfattah Kilito. Wail S. Hasan trans. Though Shalt Not Speak My Language (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008), 86.

[11]Ibid.

[12] Kilito talks about a similar experience, but notices that defense mechanism rise once the foreigner learning the language shows the same level of intimacy with the language as the native.

[13] Amazigh scholar, Ahmed Assid asserts that people lined up to buy her cassettes each time they were released. See “Raissa Kelly (2ème Partie ),” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PN_0_TG7qZs.