Saeed Taji Farouky

1 INT. OLD HAIFA VILLA - DAY Saeed, looking tired, sinks deeper into the familiar chair. His shoulders hang listlessly. SAEED Do you know what the homeland is, Safiyya? The homeland is where none of this can happen. SAFIYYA (distraught) What happened to you, Saeed? SAEED Nothing. Nothing at all. I was just asking. I’m looking for the true Palestine, the Palestine that’s more than memories...

Memory is a burden, and painful. Memory is deceitful and falsely comforting. But memory is also history, and nation. There is no true Palestine. The Palestine of memories is often the only Palestine we have.

Memory is necessary. Like other cultures resisting ethnic cleansing, we remember as a duty, though we would rather forget. Zionist soldiers stole boxes, albums, entire archives of photographs and documents from the homes of Palestinian families during the wars of 1948 and 1967 (and yet somehow I throw away old family photographs without much hesitation). In 1982 the Palestinian cinema archive was stolen by the Israeli army as they retreated from Beirut, and it has never been recovered. Every so often footage from that archive appears in an Israeli documentary, or a television news segment, then it’s like watching a hostage video. Proof of life, yes, but a reminder that your loved one is still held captive.

2 EXT. COURTYARD - DAY A middle-aged Arab man, in a suit jacket and head covering, walks slowly towards camera with his hands above his head. He looks confused. Slightly scared but compliant. He glances at the camera awkwardly. Behind him, a long line of other men also walking in step. One of them smiles to camera. In the distance, a man in military uniform is loitering, holding a gun.

Other than these ephemeral scenes, the archive is gone, so we carry around in our heads an idealized, imagined archive. We complete the scenes ourselves, write our own conclusions to the stolen narratives.

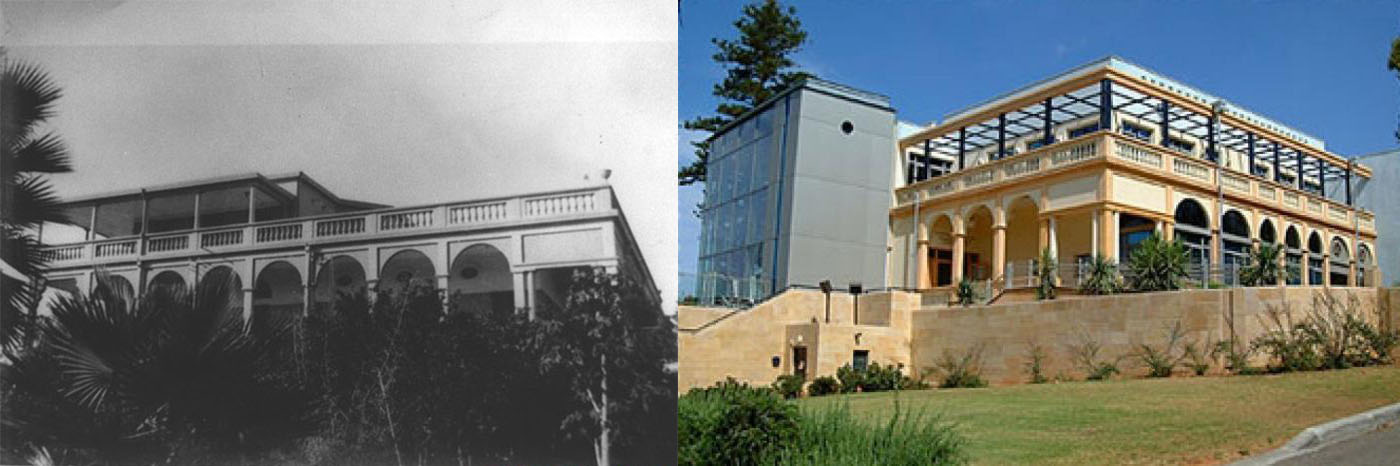

An old black and white photo of the villa of Shukri Taji Farouky. This is my Palestine. I went to visit the villa in what is now Ness Ziona, south of Tel Aviv, but an armed guard stopped me: “I’m not even allowed in there,” he joked with a shrug. The building houses the Israel Institute for Biological Research, a secret government facility, reportedly the site of the country’s biological weapons program. At the time, it wasn’t on any map. I found it by stitching together pieces from various testimonies, articles, and memories. My archaeological rendition of Palestine.

My films are full of fragmented narratives because our narratives are fragmented. The map, too, is in pieces. My story is full of holes. Some parts have been generationally forgotten, some parts buried when my grandmother told me to forget them, not to research them, to ignore them. Then she died. So I revel in these fragments and I ask the questions I’ve been told not to ask. My memory is also full of holes, punctured by years of violence and the long legacy of resulting trauma.

This is why Raed Andoni recreated an Israeli prison from the collective memory of its detainees in his film Ghosthunting (2017). Memory is our architecture, both giving us shelter and imprisoning us. And architecture is our memory. Often our most enduring recollections are of our houses: demolished, confiscated, hollowed out. We recall the walls of our grandmother’s garden, the view from the top of the staircase in our uncle’s house (we will, perhaps, never see these again). I can describe the texture of the bricks, how the light filters through the leaves of plants and brushes the window, but I can’t explain to you how to walk from one room to another. I get lost too easily in buildings.

I get lost, too, in the plot of my own films, often forgetting — when I re-watch them — that this scene comes after that scene. It’s as though I’m watching them for the first time. Eventually, I thought the most elegant solution was to abandon plot, to craft films in the same way I experience life: a sequence of brief episodes, instances, evocations, atmosphere; specters of experiences, the remnants of events. (There it is again: archaeology) In documentary film this is even more appropriate, because our lived experiences have nothing even resembling a plot. We are, instead, the collective echoes of our most salient moments.

At last, I even abandoned linearity. It happened when Thein Shwe, an oil miner in Burma, asked me “I wonder why you travelled halfway across the world to film with me? Maybe we were related in a previous life.” I realized then that it was impossible to tell a deterministic story with a man who believes he has lived, died, and been reborn thousands of times over tens of thousands of years. It was naive to say “a leads to b, which leads to c” to a family who believed this life is influenced by the accumulated karma of all their previous rebirths, and this life will — in turn — generate karma to influence the next thousand rebirths and the events in those lives and on and on until enlightenment. An intricate web of fate, luck, karma, astrology, numerology, mythology, capitalism, and politics determines all the possible trajectories of their lives. So, we talked, instead, about cosmic time. We looked not only at the clouds in their sky, but at the universes beyond them. We looked not only at the soil into which they plunged their hands, digging for oil, but deeper into the core of the earth and the primordial fire within. We told a story of cycles, coincidences, fated connections across time, a puzzle box in which every piece is in motion until the very last moment when they all fall into place.

This approach requires space. A form defined enough that we understand its boundaries, but ambiguous enough that we can move through it without a map. This is my preferred meaning of “plot”: a piece of land, outlined but empty. You know the plot’s outer edges, but within that framework, there is space through which to wander. And so I learned to love the architecture of Zaha Hadid. Her exploded, fractured designs give us the security and familiarity of a building, but with the freedom to explore, unafraid. There are walls, yes, but any conventional sense of architectural language has been pulled apart, so we no longer feel the constraints of floors, walls, straight lines. Her spaces are ambiguous and liminal, constantly in transition between wall and non-wall, floor and non-floor. Each wandering through one of her buildings is unique because each visitor defines their own route through the space, imagines their own journey.

It’s like listening to a performance by Umm Kalthoum, who recorded and performed hundreds of hours of epic songs and never sang a line the same way twice. Each performance was a new experience, a unique exploration with the audience. She would tease a phrase, repeat it, drag it out over minutes, hint at a resolution, imply to her listeners where she was going but then, at the last moment, she would hold back, change direction, return to another moment. She did this for hours at a time, her performances legendary in their length and intensity. Her audience — who had committed her songs to memory — would find her performance uncanny: both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. They would be on their feet, standing on chairs, pouring with sweat, crying, cheering, a hysterical, ecstatic trance of anticipation. Sometimes she gave them what they wanted. But more often, she withheld, leaving a phrase unfinished. And the more she withheld, the more she invited her audience to complete the phrase for themselves.

These were not linear journeys but spiritual dialogues spanning centuries of poetry, music, religion, and culture. When your storytelling is born from endless voyages across a featureless desert, the last thing you want is an efficient resolution. You don’t want logic and conclusions. You want eternity and magic. Her most effective technique, the one that had her audience in the palm of her hand, was to simply stand back and say nothing.

Silence. Empty space.

This is storytelling: unpredictable, sweaty, inefficient, liquid.

In 2004 Abdelfattah turned to me — to the camera — as I was filming him for I See The Stars At Noon and asked “what about me?” In that moment he shattered the received mythology of the objective documentary. He took a sledgehammer to the heavily constructed facade of the detached observer. His basic expression of humanity and demand for dignity changed my filmmaking and my understanding of documentary cinema forever. What about him? I would finish filming, fly back to London, edit the film, release it, move on, and make another. But what about him?

When I approached my friend, the editor Gareth Keogh, with the footage, I apologized, saying we’d have to cut all the shots in which Abdelfattah talks to the camera. But Gareth understood that those were the best parts.

And so, we made a film about making a film. A loop.

Documentary editing is a process of reverse-causality. Choices we make now define the events of the past. This is also how I write my films. I start with the feeling I want the audience to experience when it’s all over, and work backwards from there. Because I always remember goodbyes.

Consider this 9th century Arab folktale, The Tale of Attaf. The ruler Haroun Al Rashid is reading a book in his vast library, and something in the text moves him. He laughs and cries at the same time. His advisor, Jaafar, is confused by this display of ambivalence and asks how a man can laugh and cry at the same time, and Haroun Al Rashid, incensed, banishes him from the kingdom until he can understand how such a thing could happen. Jaafar goes on a long journey, a series of adventures with a man he meets along the way named Attaf. When Jaafar returns, he goes to the library to look for the story Haroun Al Rashid was reading. He eventually finds it, and as he reads, he comes to the astonishing realization that it’s the story of himself, on a long journey, a series of adventures with a man he meets along the way named Attaf.

The story, like most Arab folktales, begins with the line kan ya ma kan: “There was, or there was not,” an unapologetic assertion of fundamental uncertainty. A liminal space in which the storyteller can be both honest and dishonest at the same time. A moral ambiguity that resists the purity and truth of a conventional heroic tale.

After all, why should I write a hero’s journey when I don’t believe in heroes? Why should I tell the linear narrative of a singular protagonist when our revolution is multimodal and collective?

The founders of the Palestine Film Unit (our godmothers and godfathers of militant cinema) made a distinction between their work and the conventions of documentary filmmaking. They were not merely detached observers, filming events as they happened, but were instead active participants in those events. The camera was not a tool to record, but a weapon with which to fight the resistance and the revolution.

This is why our cartoonists are shot in the neck; left to bleed to death on Ives Street, London. And why Israeli assassins fired 12 bullets into a literary translator in the lobby of his Rome apartment. And why a Mossad car bomb eviscerated the author of this essay’s opening words. Try telling us now that culture isn’t a weapon. Try telling Naji al-Ali that cartoons are just comic relief. Try telling Weal Zuatar that literature is simply entertainment. Try telling Ghassan Kanafani that writing is a distraction from politics. Culture is a crowbar with which we can pry open the prison gate, and smash the windscreen of the limousine when our politicians pull up to the Wyndham Grand Hotel in Manama for the next round of negotiations.

The Egyptian filmmaker Philip Rizk — in speaking about برة في الشارع / Out on The Street which he co-directed with Jasmina Metwaly — makes the distinction between re-enactment, and enactment. For most of the film, the actors / workers play themselves in a re-creation of their factory strike. But near the end, they leave the set. They congregate in the stairwell of the building and begin talking off-script, joking with each other, a more chaotic expression of self-determination. They act out an idealized version of their factory strike, one in which the boss is gone and they win. But they can only achieve this because the architect-directors built with them a space in which they could roam, wander into the stairwell, disregard the set and enact their dream scenario.

My dreams are often elaborate films (ironically, the kind of convoluted adventure films that I would never make). But when I try to write them down, they’re meaningless. They were never really stories. Our dreams never are. They are only moments: jump cuts, non-linear sequences, associations and dissociations, series of images that make no sense, but that we retroactively turn into stories. They are stitched together from disparate parts, and in the gaps we fit our own experiences; we make the story about us. We’ve done the same with our nation and our map exploded into thousands of pieces.

I first dreamed of making films when I read the final words of Driss Chraibi’s novel Heirs to the Past and immediately knew that I had to one day turn it into cinema. He describes an act of digging and building at the same time. Archaeology and architecture combined. I always remember goodbyes.

3 INT. RABAT AIRPORT - DAY The overly-enthusiastic customs officer hands Driss a thin envelope. Driss turns it over in his hands. No name or address. He folds open the flap with only his thumb. His plane ticket back to France. He takes it out, but there's something else in there. A note. A single, small piece of paper with familiar tiny letters, scrawled but precise. Driss reads. DRISS (to himself) Wells, Driss. Dig a well, and go down to look for water. The light is not on the surface, but deep down. Wherever you may be, even in the desert, you will always find water. You have only to dig, Driss, dig deep.

In the last few years of her life, my mother’s memory became fragmented. She had false memories, and would forget real events. She had been an archaeologist, and had occasionally brought pieces of broken pottery home from her digs. As a child, I would feel their sharp edges, wondering how they fit together, where the missing pieces were. Once, our family dog tried to eat a broken flower pot, cutting his mouth. Blood stained the pottery. I kept it for years as a memento, another fragment of history, a relic of his suffering like the prophet I believed him to be. I often fell asleep on his belly, inhaling his fur, whispering to him that he was the only sane one in the family. I remember this. Eventually that image will become a scene in a screenplay, no doubt. But it will be more than merely a reproduction of a memory; I will need to fill in the gaps, like the threads of gold in Kintsugi. In this scene, reclining on his dog, the young man will be reading Ghassan Kanafani’s Return to Haifa. He will like the fact that the main character has the same name as him, and he will imagine one day turning the book into a film.