Maya Abu Al-Hayyat’s No One Knows Their Blood Type crafts a deeply intimate portrayal of Palestinian life, offering a nuanced, defiant exploration of identity, memory and belonging.

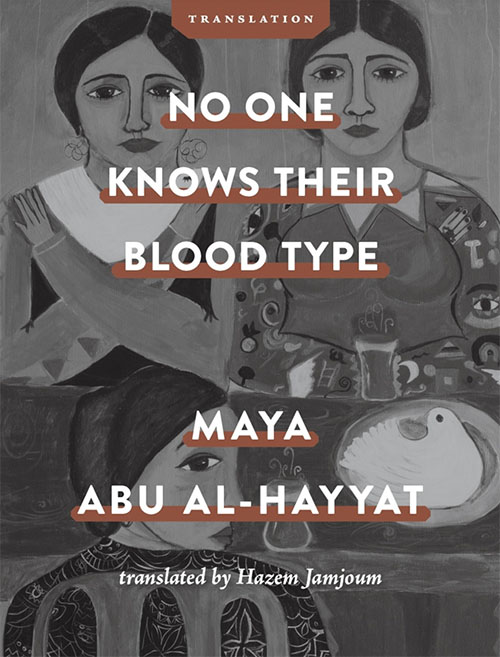

No One Knows Their Blood Type, a novel by Maya Abu Al-Hayyat

Translated by Hazem Jamjoum

Cleveland State University Poetry Center 2024

ISBN 9798989708413

Zahra Hankir

In his piercing afterword to Maya Abu Al-Hayyat’s novel No One Knows Their Blood Type, Palestinian translator Hazem Jamjoum asks, “What do we center when we want to speak to us? When we’re not trying to tell others about what we fight against and what we fight for when we fight for freedom?” Jamjoum invites us to imagine a discourse unbound by the burden of explanation to the foreigner — one that flows from a deeply intimate knowledge of shared struggle, memory, and aspiration.

By centering this question of narrative ownership, Jamjoum highlights the radical potential of Palestinian stories like Abu Al-Hayyat’s to resist erasure. He reframes the text not as a plea for understanding from Western readers — an assumption some might make given its English translation — but as a reclamation. On the decision to translate from the mother tongue, he insists, “As a majority exile society, one whose colonizer’s strategic objectives revolve primarily around ensuring that as few of us remain anywhere near the land that unites us as possible, to be Palestinian is not necessarily to read Arabic.”

No One Knows Their Blood Type embodies this focus on self-centered storytelling, where Abu Al-Hayyat refuses to indulge in trauma. Instead, she immerses readers in the complexities of Palestinian life, including — but crucially not limited to — the oft-repeated notion of resilience, or sumūd. Her narratives are alive with joy, secrets, betrayal, humor, love, care, and connection. The slim novel reflects an intimate, inward gaze, declining to offer itself up for voyeuristic consumption. As such, it transcends Western-imposed binaries of victimhood and heroism, weaving together both the mundane and the turbulent.

•

First published in Arabic in 2013, No One Knows Their Blood Type traces the lives of Palestinian characters across different epochs and locations. The story begins in 2007 in Jerusalem with the death of Malika, a revered midwife, whose passing sets a series of life-changing events into motion. Jumana, who is grappling with her father’s illness in the same hospital, comes upon a startling revelation about her blood type that throws into question everything she believes about herself: Could she, after all this time, not be the daughter of her father or the sister of her sister? Could she, by extension, not even be Palestinian? And what would this mean in practice when her lineage has shaped her entire life?

Jumana’s childhood was already fraught with upheaval. Her father, a PLO fighter-turned-administrator, moved her and her sister Yara from Beirut to various other cities, separating them from their Lebanese mother. The nonlinear story reflects these movements, tracing a journey that mirrors the author’s own life as a Palestinian across Jerusalem, Beirut, Amman, and Tunis. We follow Jumana and Yara as they navigate family estrangement, displacement, motherhood, and marriage. Alongside their relationships with their difficult father, the book incorporates the lives of extended family and community members.

Through shifting timelines, No One Knows Their Blood Type attempts to preserve a sense of home — an elusive and fluid concept. “How do you return somewhere you’ve never been?” contemplates Yara. “I don’t understand why we have to feel how everyone wants us to feel. The only things I know about Palestine are what Mr. Khairy, the history teacher, tried to teach us, making us memorize our country’s map while threatening us with his shoe.”

The novella shuns neat narratives. It foregrounds the messiness of survival under Israeli occupation and the sobering realities of life in exile. Women are central to the story — they are at once mothers and daughters, docile and furious, caretakers and rebels. Often, they shoulder the burdens of nurturing familial bonds while confronting patriarchy. One such thread culminates in an act of brutality so casually executed that it chills with its stark realism. Here, the woman’s body itself becomes both battleground and resistor.

The book’s titular metaphor evokes a quiet tension between visibility and erasure. Bloodlines become markers of belonging and dislocation, offering strength while also underscoring the weight of exclusion. Though the book’s themes are heavy, Abu Al-Hayyat’s prose — rendered beautifully by Jamjoum — carries a light touch, coaxing this reader into laughter as frequently as reflection. (In one scene, Jumana’s daughter micturates on the road “like an Olympic champion in the sport of roadside urination.” In another, Abu Al Saeed imagines telling his office director, “You’re as inconsequential as a puddle.”) Jamjoum’s debut literary translation is unforced and lyrical, bridging worlds without diluting the text’s essence. The language is layered, somehow sparing, while also overflowing with abundance.

In the context of Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza, No One Knows Their Blood Type feels especially urgent, though one could argue this urgency is not new. The novella does not seek to explain Palestinian resistance but rather to root it in the textures of everyday life. As Jamjoum writes in the afterword, the narrative “assumes the grotesque facets of the workings of power and conducts its conversation with whoever recognizes themselves as already in the fight.”

Within these pages, the reader enters doors that may otherwise be closed and is invited to examine rich inner lives that evade reductive depictions. Even the novel’s most troubled characters find solace in interpreting and reinterpreting their lives, consequently repudiating the elimination the occupation seeks relentlessly to impose.

This is perhaps the novel’s greatest achievement: its refusal to romanticize suffering or simplify its characters’ struggles. “We should talk about love and hope,” Abu Al-Hayyat said during an online event marking the book’s launch. “I hate romanticizing… what’s happening; it’s brutality, it’s killing, it’s the worst thing happening in humanity. But we need to talk about this through literature and art saved me. I think it can save the new generation and maybe other generations.”

Well, as the mother of a daughter who was born of a violent &;impregnating rape by her father from Bethlehem. Fuad Nackleh Kattan. A rbetraying rape so horrific that I blocked its memory for 52+ years. The horror which never ends. As his abandoned daughter born of his rape has tried so hard to be accepted by her birth father. Only to be weaponised, demonised and ostracised by Fuad, ichelin Dabdoub-Kattan, Fadi Karim & Muna Katan. Who all spiel reverence for all humanity as despicable hypocrisy.Do read: I WENT TO BETHLEHEM TO FIND MY FATHER – by Liza Foreman It is online by FATHMAWAY. To read Fuad Kattan’s reviled eldest daughter’s elegant account of their heinous inhumanity.All real & hideous Palestinian dramas are here. Ya haram! But thankyou to the Chancellor of Bethlehem University for trying to encourage the KATTANS to behave as decent humans to his reviled daughter born of his rape. Alas he failed. The London Met are now investigating my recently reported historical rape. As thr heroic Gisèle Pelicot says: THE SHAME-HAS TO CHANGE SIDES…..