My greatest regret was how much I believed in the future.

—Jonathan Safran Foer

Joumana Haddad

It’s the 24th of October of the year 2023. As of today, I’ve been alive for twenty-three years, but all this time, I’ve never really been in my life. I mean “inside of it.” All this time, I’ve been watching it unfold from a close distance: a helpless and appalled audience of one.

Let me try to describe it better to you: Imagine a prisoner in a cell. Now imagine the cell has a low ceiling, so that the prisoner is always either lying down or on her knees (well, she’s mostly on her knees). Now imagine the cell has no door, no windows, not even bars. It’s like a sealed box. Let’s call the cell Gaza. Can you picture it? Good. Now imagine that the walls of the cell, even the ceiling and the floor, are a panoramic, 360-degree screen. On that screen, the prisoner is forced to watch a silent black and white horror movie over and over again, where only the color red, and the sound of screams, are discernable. It’s quite an immersive experience: wherever the prisoner turns, the movie is there, waiting for her. If she closes her eyes, she still sees it. If she covers her ears, she still hears the screams. The movie is all around her, it penetrates her from all sides, but she’s not “in it.” Do you understand what I mean?

I came out of my mother’s womb and slid right into the cell. I didn’t need a doctor’s slap to cry: You see, tears are my people’s words, and I had already mastered each one of them from inside mama’s belly. It wasn’t so hard anyway. There is one main word in our dictionary, “loss,” and every other word branches out from it. Loss was in the lullaby mom sang for me every night before I came out of her. Loss was in her bawling the day her three sisters perished all together in one single airstrike. Loss was in the disheartened chirping of the birds in our small cherry tree. Loss was in my father’s throat especially, when he told his parents that his younger brother, their only remaining son, had also died. “We lost Tarek,” he whispered to them that day, and all of humanity’s sorrows, from the beginning of time, seemed to be concentrated in those three words.

At first, I used to believe the cell was the world. Then I went to school, and I opened books, and I saw other worlds in them, very different from mine. I used to ask my dad: “Why don’t we have a sky, baba?” and he’d say: “Skies are for those who can afford wings, my love. We can barely afford bread.”

Life in the cell was usually quite repetitive: wake up, make sure you still have all your limbs and all your family members, try to forget where you are, try to survive who you are, then go to sleep again. But sometimes, sudden, suspenseful twists would occur in the horror movie, and the terror in it would intensify, and the violence in it would be heightened. The first time this happened, I was eight years old. The writers and producers of the movie, the Israelis, called that twist Operation Cast Lead. The movie’s cast, who are Palestinian (the cast is always Palestinian: it’s as if we were born to play these roles), preferred to call it the “Gaza massacre.” They felt it was more fitting. My father, right before he was decimated by a rocket, told me that the movie had started long before I was born. In 1948 precisely, he said. I had already intuited something was wrong: the persistent fear in my mother’s voice, when she breastfed me mixed with her milk; the immeasurable sadness in my grandmother’s eyes, which no hug seemed to ever cure; the way my granddad caressed the plants in our small garden every evening with his trembling hands, as if he might not see them again the next day… When, on December 27, 2008, the neighbors brought in my older brother’s bleeding, lifeless body and laid it in our front yard, I was appalled. I called his name over and again, “Mahmoud, Mahmoud!” But he wouldn’t answer. He just lay there, like an open scar in our house’s heart. Was he angry with me, I wondered? But he didn’t seem angry. His young, beautiful face was trying to tell me a story. Not like the funny stories he used to invent for me before bedtime. This one was different. It didn’t speak of cheerful kids and gorgeous princesses; it didn’t exude joy and magic. It didn’t end with “happily ever after.” This story had a beginning but it didn’t seem to have a finale. It was a haunting tale of boundless suffering and torment.

As I was observing Mahmoud’s still legs, those tireless legs that used to walk miles to find us food, or potable water, or hope for the day, my mother came out of the house and immediately started gasping for air, as if she wanted to yell but couldn’t. She looked like a gazelle fatally bit on the neck by a predator, blaring her agony in deafening silence. She fell on her knees next to Mahmoud and shrouded him with her arms. That is when I tasted my tears for the first time. I had cried before, but never had the salt of sorrow burned the corners of my mouth this achingly.

That same day, we were told my father had died too. When the airstrikes started, he heard that the police station nearby had been hit, so he left in a hurry to check on his uncle, a policeman. He never came back and we never recovered his body. More than two hundred people died as well, many of them children, because the attacks had begun at the time when kids were leaving school. Despite the immensity of her loss, my mother was still unable to cry. She just sat on the floor with empty eyes, looking at something that was invisible to the rest of us. Now I know it must have been her agonized soul. It couldn’t bear staying in her body so it became a separate entity, an object she could stare at as if it wasn’t hers. It was too heavy, too vicious, too insufferable to be hers.

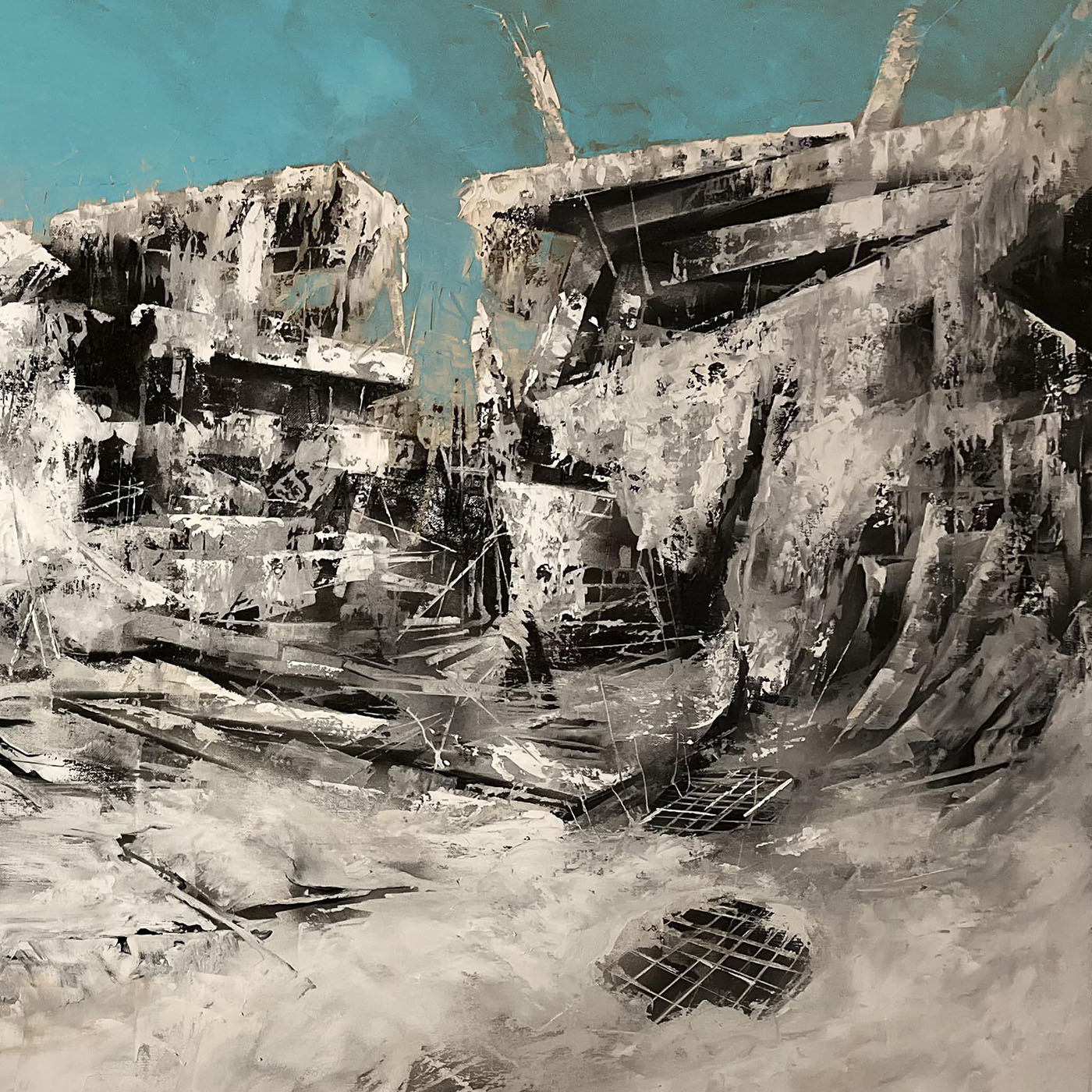

The second time there was a twist in the movie, it was November 2012 and I had just turned twelve. The Israelis called it Operation Pillar of Defense. We just called it “another massacre.” What’s the use of all those titles? We got tired of giving names to our serial bereavements. The Israelis should have done the same and just called it “another crime.” But then again, they need the fancy appellations in order to justify the bloodbaths, don’t they? Butchers always do. Anyway, this time around, I tried to be brave. I kept my eyes and ears open, praying that the ending would be different, but it wasn’t. My best friend Mariam was killed; her whole family too. Completely wiped out, as if they never existed in the first place (sometimes I wonder if it wouldn’t be better if one never existed in the first place; sometimes I find myself envying the unborn). My cousin Alaa was also killed, and his brother Ziad lost his right leg. The shelling was so violent that we had to leave home and seek refuge at my aunt’s place, which had a basement. Only my mom and my younger sister and I went, though. My granddad refused to leave the house, and my grandma refused to leave my granddad. When we returned, the house was mere debris, and my grandparents were other debris under the debris. The plants were gone too; only the traces of Seedo’s trembling hands remained in the air, remnants of a love story that would never end. “Woefully ever after.” I started having nightmares whenever sleep came. But the nightmares I saw when I woke up were way worse.

A third twist in the horror movie occurred in July 2014 (Operation Protective Edge, you said? Stop your impudent, ridiculous lies already and have the guts to call a genocide a genocide!). The prisoner had by then learned her lesson well. She knew she was completely helpless, unable to change anything in the fate of the movie’s protagonists. Most of the world’s leaders were siding with the criminals: power was with them, money was with them, the media was with them, etc. Whatever she did or didn’t do, whomever she implored or begged, the prisoner knew that the people she loved would be slaughtered, they would be dismembered, they would be exterminated, their heads would roll.

She also knew that she, too, would play a part in the movie, even though she wasn’t “in” it: she would weep, she would hurt, she would grieve, she would “lose:” Both her parents and her only sister. The prisoner accepted — at least until further notice, when Justice would stop being a fable or a mere statute in unjust courthouses in unjust countries — that this was her life: a horror movie seen on a black and white panoramic screen where the only discernable color is red and the only discernable sound is screams.

So, the horror movie kept playing around me in a loop. Meanwhile, I grew up. Meanwhile, I became a teenager, then a young woman, then a bride, then a mother of two, a girl and a boy.

Her name was Amira, and on October 16 of this year, she was four years, twelve weeks and three days old. She loved to sing and had a beautiful voice. Her hair always smelled like happiness if happiness had a scent. Amira was sleeping in her tiny bed, embracing her woollen doll, when the building we lived in was bombed, causing the concrete walls and columns to collapse over our heads. Only a few survived: Amira’s dad and I, as well as her younger brother, and her doll, but not Amira. Unfortunately, my Amira wasn’t made of wool like her doll. A pillar had fallen on her bed and her body had scattered into pieces under the rubble. When rescue groups tried to look for survivors, they only found a doll crying while holding the limbs of a little girl called Amira.

His name was Mahmoud (like my brother’s) and he was two years old. He was frail like a bird and his eyes constantly spoke of terror and despair. As if he knew what awaited him, as if he saw what was coming. After our building got destroyed and we lost Amira, we sought refuge in the Al-Ahli Arab hospital in the Zeitoun neighbourhood. On October 17, Mahmoud was trembling in my arms because of the rockets falling on us from all sides. He kept asking me: “Why did we leave Amira behind?” and I didn’t know what to answer. I just kept whispering to him: “Don’t be afraid, my love. It will all be over soon.” But the blasts kept going. Mahmoud’s little hands were shaking, he closed his ears so that he wouldn’t hear, he closed his eyes so that he wouldn’t see. Then there was a big explosion, the biggest of them all. I lost consciousness. When I opened my eyes, everything was gone: the shelter, the people, my husband and my Mahmoud. The only thing left intact was the sound of my voice telling him: “It will all be over soon, my love, it will all be over soon.”

Today is the 24th of October of the year 2023. More than 10,000 people have been killed so far in this nth sequel of the horror movie that is our life since 1948. A third of those are children. Thousands of little kids like Amira and Mahmoud, who could have grown up, who could have gone to school, who could have had beautiful voices, who could have fallen in love and gotten married and had children of their own.

They keep telling me that we can do it all over again. They keep saying that not all hope is lost; that only two of us can repopulate the whole land of Palestine if we had to. Repopulate it with what? More future cadavers? More prey to appease the insatiable belly of the beast? I know this might sound like blasphemy, but we are tired of giving birth to martyrs. For once, we would like to see the plants in our garden develop strong roots and become trees. For once, we would like to not have to rebuild our demolished homes from scratch. For once, we would like to not see our hearts smashed under the rubble. When will morning come and wipe out the blackness of this interminable night?

My name is Hanan, and I am from Gaza. I’ve been alive for twenty-three years now; I’ve been alive for countless losses. Shouldn’t I rather say that I’ve been escaping death for twenty-three years? For what is a life, if all it has offered me so far is a past that looks like a mortuary, a present that is an open morgue drawer with my name on it, and no promise of a tomorrow whatsoever?

I must go now. The drawer is calling me, and I really miss my family.