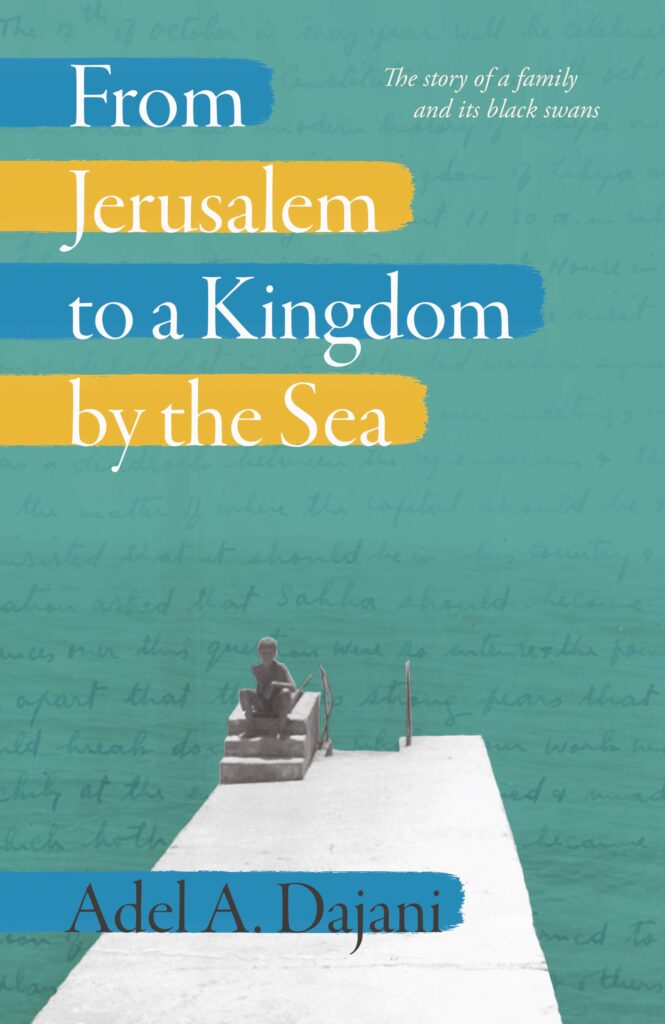

From Jerusalem to a Kingdom by the Sea, a memoir by Adel A. Dajani,

Zuleika Books (2021)

ISBN 9781916197770

Prophet David was recognized and revered by Jews, Moslems and Christians. Although not fashionable nowadays in the black-and-white sound bite of political correctness, these monotheistic religions had at least agreed on their prophets.

Rana Asfour

In 1529, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent gave a firman (declaration) bestowing on Muslim Sufi mystical leader Al Sayyid Sheikh Ahmad al-Sharif and his descendants the custodianship of the King David Tomb in Jerusalem. “The family was hereafter to be known as the Dajanis or the Daudis (‘Daud’ is David in Arabic) as an honorific emblem for the Moslem family entrusted with looking after the Tomb of the Prophet David.”

And so from that time onward, the residents of Jerusalem gave the Sheikh and his descendants the title of al-Daudis. Additionally, the Cenacle — the room of the Last Supper, reputed to be located on an upper floor of King David’s Tomb — was also under the custodianship of the Dajanis.

However, in 1948, with the establishment of the state of Israel in Palestine, the uninterrupted “umbilical connection” with a country that was the Dajanis’ home for over a thousand years, dating back to AD 637, was cut at a stroke, writes Adel A. Dajani in the opening chapter of his memoir From Jerusalem to a Kingdom by the Sea, and with that the family, whose surgeon patriarch had founded the first private hospital in Jaffa, “lost all its possessions, identity and the dignity of belonging” in what the author names as the first of the “black swans” — unforeseen events with extreme consequences — that would upend the family’s life time and time again.

Adel’s parents, Awni and Salma, with almost nothing but “the clothes on their back” initially fled the Nakba in Palestine to Cairo for what they thought would be a short stay, while things settled down enough for them to return to their Jaffa home. As it soon became apparent that they would be among some three-quarters of a million Palestinians forced into permanent exile, Adel’s father decided that it was time to look to a future outside his homeland.

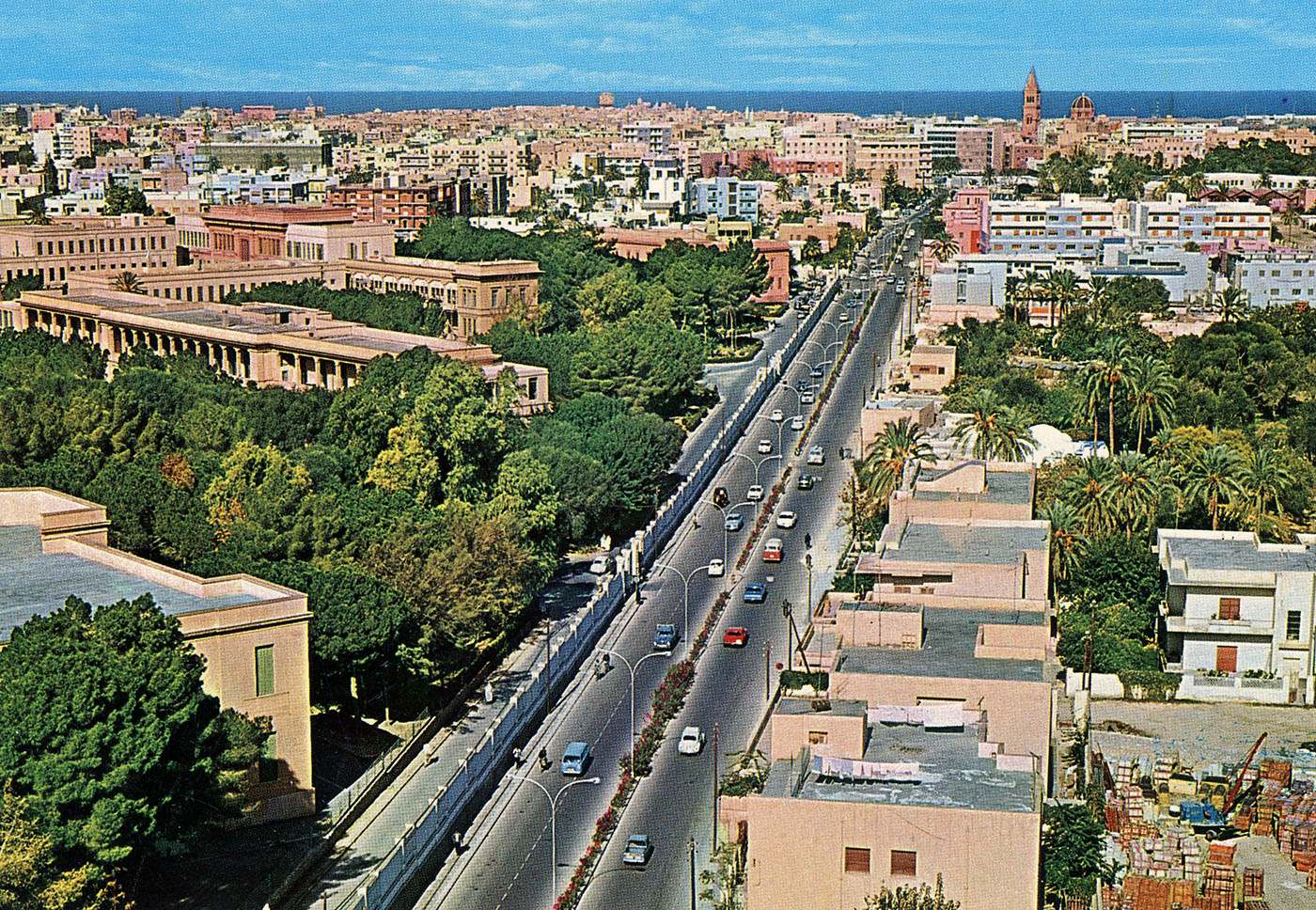

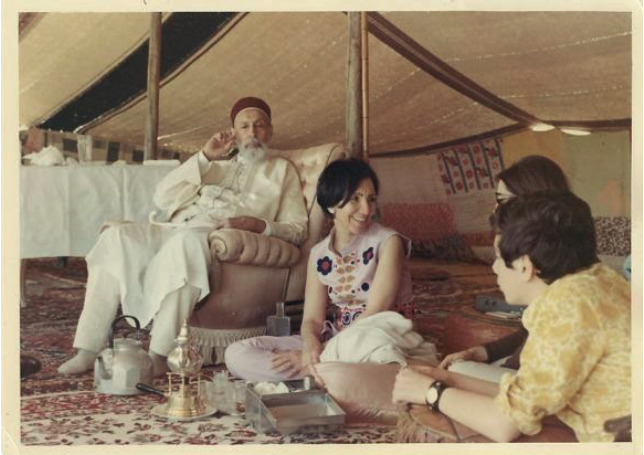

And so, from Cairo the family moved to Libya in the early 1950s after Awni, an Oxbridge graduate, and barrister of the Middle Temple, secured a position as the bilingual and multicultural legal advisor to the Royal Diwan of Prince Idris Al-Senussi of Libya. Although the country at the time was a poor one with no natural resources, dependent on the indulgence of the international community, Awni found himself right in the middle of a crucial time in the country’s history as he played a major role in the formulation of the nascent constitution of the country, which needed to precede the formal declaration of a newly independent state in October, 1951. Meanwhile, Adel’s mother, Salma, and the future Queen of Libya, Fatima Idris Al Senussi, the daughter of Freedom Fighter Sayyid Ahmad Sharif Al-Senussi — leader of the Senussi religious order that fought against the Italian colonizers — formed a close friendship.

“The baptism by fire of the creation of the Kingdom of Libya anchored the relationship of growing friendship and mutual respect between my parents and King Idris and Queen Fatima,” writes Dajani. “It was this deep bond of family with the royal family that marked my childhood and that of my siblings and defined our journey into the magic Kingdom by the Sea.”

And thus it was into this charmed milieu that investment banker and writer Adel Dajani was born in Tripoli, Bride of the Sea, in 1955, whisked from the hospital to the royal palace, upon the insistence of Queen Fatima, whom Adel would later address as “Mawlati” (your highness) while his parents’ apartment in Tripoli was being refurbished. Furthermore, Awni asked the King to name his newborn and he chose the name “Adel” which means “just” in Arabic.

And so begins a most exceptional part of the memoir that offers a first-person account of a monarchy about which little is known, since the coup d’état by Colonel Gaddafi brought it to an end on September 1st, 1969. It wasn’t until the uprisings of 2011 against Gaddafi’s ruthless regime that posters of Libya’s “first and last” King would re-emerge on the liberated streets of the country, heralded by revolutionaries who were not even born when the King died in exile in Egypt in 1983.

What Dajani’s memoir does is offer insight into the mind and heart of a benevolent, down-to-earth monarch, one who was in touch with his Sufi practices, with a profound love for his country, his people and most of all, his Queen. Although Libya was impoverished, King Idris wielded significant political influence, banning political parties to replace Libya’s federal system with a unitary state in 1963. Many still look to his era as a golden one in which after the discovery of oil, the country caught up with the world economically, politically and socially while building its modern infrastructure. At a time when at present, the “Libyan people have become despondent and disillusioned, and many are impoverished whilst the state is selling over one million barrels of oil per day,” writes Dajani, the words of the “wise” King of Libya ring ever truer: “I wish you had told me we had discovered water.”

The memoir oscillates between Dajani’s family history in the Old City of Jerusalem and the orange groves of Jaffa, to the spires of Oxbridge in the 1930s and to post-war London in the 1950s. Later on, the we move to Adel’s personal history that includes adolescent summers spent abroad with Libya’s King and Queen and their adopted daughter Suleima drinking tea and dining with the likes of President Nasser of Egypt, and King Paul of Greece. Dajani then goes on to his schooling, first at the British-run Tripoli College before heading to Eton as the first Arab and Libyan purportedly to go there, and where he used “to spin all sorts of stories, mainly from One Thousand and One Nights, about my pet camels and so on. And the thing is, people believed them.” Since then, the family has established a travel grant for school leavers to go to the Arab world as part of a research assignment to better learn about the region. Dajani’s two sons have subsequently gone on to attend Eton, following in their father’s footsteps.

The giant [Ben Ali] was made of salt, and the realization that people once empowered, can get rid of dictators was a liberating and euphoric feeling.

The narrative takes a darker turn as the author’s father Awni is imprisoned in Gaddafi’s jail following the fall of the monarchy and later the family’s flight from Tripoli to Tunisia, as yet again as in 1948, their property is confiscated and they are forced to abandon a beloved country. Adel, in subsequent chapters, writes about his marriage and a career in finance that finds him gambolling between the UK, Hong Kong and Tunisia.

It is nearly 40 years after his witnessing the fall of the monarchy in Libya, that Adel and his family are witnesses to the arrival of another “black swan” at their doorstep: the 2011 popular uprisings in Libya and Tunisia against “unemployment, poor economic mismanagement, corruption and political autocracy.” In his chapter on Tunisia, Adel describes the atmosphere in the streets in the early days of the uprisings as “a friendly buzzing cocktail party, with people going out of their way to be supportive and caring.” However, it quickly became apparent that with a power void created by the fall of the regime, “the only protection was going to be local neighborhood watches.”

In Libya, things were not much better as the family’s assets were again being seized, this time by thuggish Libyan squatting families fueled by the Gaddafi slogan that “the house belongs to whoever is in occupation” and that “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” Adel soon found himself engaged not only in trying to secure his property but discovered that he could also be useful as an agent of international media mobilization through his various network of contacts and journalists, and through financial and humanitarian support.

Unlike the Palestinian/Israeli conflict where people feel mostly helpless in influencing the course of events, Libya, at this critical juncture of history, was different. Anyone who engaged could make a difference.

And so, it is throughout Dajani’s narrative chronicling the events in Libya and Tunisia as well as his attempts to salvage his business within this maelstrom, that it becomes fascinating to observe how the making and dissolution of the Dajani family’s personal gains and losses has always played against a backdrop of the continuously shifting powers in the Arab world, whose colossal effect on this family have continually forced it to adapt in order to survive and re-build, yet in the interim, leaving it in a perpetual search for a place to belong.

As the memoir begins in Palestine, towards its end, it comes full circle as father and son return to the land of their ancestors. Adel’s son, Rakan, an Oxford graduate, is working on a dissertation inspired by the Banksy Walled off Hotel in Bethlehem. Their trip together is a chance to examine the feeling of ambivalence of identity and exile that all peoples of exile feel, a feeling that Edward Said so eloquently captured in his writings, in particular his memoir, Out of Place.

Part of the tragedy of the Palestinian exile is that even in death, most Palestinians are not allowed by the Israeli government to be buried in their country of origin. For my father this would have been in the Dajani cemetery along the ancient walls of Jerusalem, but like so many other Palestinians, he was deprived of this choice of burial in the land of his ancestors.

Dajani writes about how “tragic and ironic” it was to see that the family bestowed with protecting King David’s Tomb had had its cemeteries desecrated by extremists, so that “not only the living but even the dead Palestinians are not spared by this ongoing colonial occupation.” He also wistfully noted that the family patriarch, Awni Dajani, had to be buried not in his beloved Jerusalem, but in Tunisia. Dajani further shows how Arab residential areas such as Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are methodically being taken over, “rubber-stamped by an Israeli judicial system.” What is particularly tragic, he adds, is that “the Arab Jerusalem residents have few weapons of resistance in the face of an international community that has given up and a political leadership that has failed them.”

As Adel leaves Palestine to head back to Jordan, with questions on home, legacy and roots still preying on his mind, he is mesmerized “by the beauty of the sunset over the lifeless Dead Sea that straddles the border between Jordan and Occupied Palestine and that of the contrasting sunset on the sea of the Mediterranean: calm, changeable, mercurial, tempestuous but alive,” like his ongoing journey from Jerusalem to the Kingdom by the Sea.

Beautifully written, Dajani’s memoir spans five decades and manages to sensitively capture the trials and tribulations of generations of Dajanis to reveal a family committed to resilience in the face of adversity. It is a Palestinian story of sumud, steadfastness, in the face of the “Goliath of Occupation.”