In memory of my father

Dima Mikhayel Matta

These are stories I rarely tell. These are stories I keep close to my person. Not in my pocket. No, closer. I keep them on my chest the way my grandma kept money under the strap of her bra. They are unspoken because of the fear that what is spoken might be spoken into being. But this is not how storytelling works. I have to share this story so that you can stand in it with me.

My dad has cognitive impairment. This means that he loses his short term memory. I’m okay with my father forgetting what he had for lunch, but I’m not okay with him forgetting that I told him the story of where the saying ‘عالوعد يا كمون,’ ‘promises to cumin are not kept’ comes from. I tell my father short stories that are familiar to him. Short so that he remembers the beginning by the time we reach the end, familiar so he can conjure the images in his mind. The story about cumin is one of them, and I must have told it to him three or four times, whenever I want us to appreciate the beauty of the Arabic language.

Cumin does not need a lot of care, it doesn’t really need to be watered. The story goes that, seeing the gardener water the other plants one day, cumin became jealous and asked the gardener for some water. The gardener said “tomorrow, tomorrow” but never followed up on his promise. Dad thought it was a beautiful story when he heard it. I know that his memory of stories that he hears fades, but the feeling of enjoying it stays with him, which consoles me and gives me solace. In Old French and Latin, “solace” means “pleasure, enjoyment,” but I wouldn’t go that far. It gives me solace as in it helps me not fall apart as much. Cumin is a very lonely plant.

Dad’s memory is him holding his stories like water in his palms. Every time he holds them, details get lost and the stories change. But this story about memory loss has never been about precision. This has always been about grieving. I am losing these stories because I didn’t gather them earlier. I see the empty spaces that they used to occupy in my father’s mind. They make me sad and scare me at the same time. They make me sad because I see how it frustrates him to forget and then he becomes upset with himself. There is forgetfulness, cognitive impairment, and there is the awareness of it, and that is a harsher space to inhabit.

A friend in med school told me that, on one of her rounds, they met a woman with advanced dementia. She was happy. They didn’t need to give her medication. She had no worries and did not remember sadness. The doctors said she was delirious, connoting madness but also, and perhaps equally, happiness.

“Did she speak?” I ask my friend.

“No, she was all eyes, and made little sounds. Her family had left her alone at the hospital and did not visit.”

“Then how did they know she was happy?” “They said she was in her own world.”

Her name was Nadia. Her name means tender and delicate. Right now, forgetfulness seems anything but that. Right now, what I think it must feel like for my father is a constant slipping, a tearing-away of. Or maybe this is what it feels like for me to witness it. Either way, I am not happy.

My lover sends me their music. They follow it with, “It’s not done yet, but these are the main ideas.” Sounds are their ideas and I tell them it’s magic. They don’t believe me, but I know. Maybe that was what Nadia was doing, creating little sounds, ideas of happiness.

I don’t have this skill. I need to find the right word for everything I want to say. And, when I do, I feel the satisfaction of a work well done. No, I feel the reassurance of having control. As a theatre maker, I spent years taking a lot of acting workshops and some clowning classes, and in many of them we would be asked to make random sounds, or sometimes more specifically, the sound we felt like in that moment. Mine was often a sad moan, of an animal in pain. I’m afraid I can’t make sound ideas. I’m more afraid that this is the only one I have. And I’m afraid of what this says about my words. I told my lover that I have all the words to say specifically what I think and feel. I’m clear and easy to understand. Then I told her that I also have all the words to cover my unwillingness to say what I specifically think and feel, and that is another gift — though it doesn’t feel like one when it serves to gild the sad sound. There are no painted lilies in memory loss.

Maggie Nelson wrote: “I gained an outsized faith in articulation itself as its own form of protection.”[1] I know what she means.

Now, when I think of the pause my dad takes in the middle of a sentence, I don’t think of it as a slipping-away any more. I think of memory loss the way I think of a black hole, a place where gravity is so strong that it pulls everything into it. Objects are stripped of their agency. My father is being stripped of his stories.

The mind is a very lonely organ.

What will I be when I am stripped of words? Not this.

Who will my father be when he is stripped of stories? I don’t want to think about it.

When we leave things out, the space they inhabited stays. The things my father leaves out because he has forgotten them; their space is filled with silence. Like a star’s center falling in upon itself, collapsing.

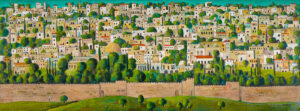

Let’s say you are reading this while sitting on your balcony. And let’s say you look up and you find a constellation that looks like ellipses. That’s Orion’s Belt. You will think of silences, of sentences left unfinished, of memories you have forgotten, which really you can’t think of. We can’t remember what we don’t remember. Then you will think about that time when you were a kid and you were in the back seat of your parents’ car. You looked out the window at night and thought the moon was following you. One day, you will read an article about how the bright red star in Orion might be dying, the title will read, “A giant star is acting strange.” You will read this and read about how so many stars burned themselves out. You will know that there is a significant likelihood that the stars you pointed to as a kid — the ones that form ellipses, and the ones that don’t — are no longer there. And you will realize that by pointing upward, to the sky, you are marking the past with your index.

A star is a very lonely celestial body.

Maggie Nelson writes, “I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do. It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude. Loneliness is solitude with a problem.”[2]

We construct our queerness, don’t we? Mine doesn’t look like yours. My friend explains that a queer space is one where you don’t have to explain yourself. But I find myself explaining myself to myself. Is my mind not a queer space? Is my body?

I tell my therapist that I know when I’m unwell because that’s when I can’t stand being alone. I turn on the TV if I’m home; I need to hear dialogue, even if I’m not part of it. I make so many phone calls, I call whoever has time for me. Tell me everything about your day. Did I tell you that I can only memorize one joke at a time? Want to hear it? I find it impossible to read. The silence gives too much space for thoughts that I’d rather not welcome. This also means that it’s impossible to write. I tell my friend that I’m watching Christmas movies in September and I invite everyone over for coffee. I don’t mind not being a writer during these times, but it is painful that I don’t find comfort in the written word.

I don’t know how to find dignity in my loneliness. Most days, I don’t think there is any.

During the Lebanese revolution in 2019, I cut my hair short, I stopped wearing lipstick and I started wearing button-up shirts. Some days I wished that my breasts were smaller, so small that the button-up shirt would hang loose over my chest. During lockdown, I would often look at my naked body in front of a mirror. I would look at the curves, admire them and then sometimes wish they would disappear. Some days I would celebrate them and other days I would move around, stand sideways, then shift, bend my knees a little, and imagine what it would be like if I had more muscles, fewer curves, broader shoulders. What was it that I wanted? The possibility of being both. Neither. Bend gender to my will. Genders. Plural. I call a friend, they tell me that they’re considering starting HRT. Then they say: ‘It’s hard to perform our new gender identity when there is no audience.’ It’s hard to rehearse it when no one is watching. Am I “they/them” in my own bedroom, alone?

I visit my parents. I sit on the balcony, with a mask; they stay indoors, their sofa turned towards me, four meters away. My mother tells me that she found the books she used to read to us when we were kids and that my sister didn’t want to take them for her son. My sister tells her: “These books aren’t for boys.”

I say to my parents, “I really don’t know how I turned out to be so …” I paused. I was searching for the words “radically feminist” in Arabic.

My dad volunteers to finish my sentence: “Mannish?”

I laughed. He didn’t mean to criticize or offend me, he meant to help me finish my sentence. I never thought I’d hear this word said with so much sweetness, with such a genuine want to find a way to describe me, to offer me to myself at a time when I couldn’t do that just yet.

We construct our queerness, don’t we? Mine doesn’t look like yours. My friend explains that a queer space is one where you don’t have to explain yourself. But I find myself explaining myself to myself. Is my mind not a queer space? Is my body?

Strangers talk to me less and frown at me more now that I look the way I do.

A queer body is a very lonely structure.

When I was five years old, I found a rock in a garden. The rock was the size of my two adult hands, and it looked like a crescent moon. The kind of moon that looked like the side of someone’s face. One eye. One nostril. Half lips. I took it home and cleaned it with a toothbrush, which is what I assumed archaeologists did; I really wanted to be one at the time. I wanted to hold the rock while I slept. It felt like such a discovery, but I’m not sure why I wanted it next to me in bed. As you can imagine the rock was too rough, and dreams of sleeping with a crescent-moon rock were soon abandoned. I had trouble letting things go when I was a kid. Maybe I still do. I remember crying when my mother wanted to throw away my old sneakers. I fished out my little pillow from the trash can when I came home after school and didn’t find it on my bed. The pillow belonged to my three siblings before me. It was so old and so used that whatever was in it had turned to powder and was spilling out of the pillowcase. I hung on to it for a few weeks before the mess it made became unbearable and I threw it away myself.

I remember moments like these randomly. When I’m having coffee, showering, going to the bathroom in the middle of the night. I remember keeping a raw egg under my pillow, thinking I could make it hatch. I remember wearing a dress with pockets and putting plastic cookies in them so I could pretend to eat them and either grow very large or shrink to fit in a glass bottle, like Alice in Wonderland. I remember tying a string to the back of the couch, climbing on it and pretending I was riding a horse. Then I remember some of the times I wished I had a couch near me when I told this story, so I could show people where I tied the string and where I climbed. I created a tidy narrative that spending all this time at a young age making up stories, acting them out and pretending to be characters from books and movies, made me the writer and performer I am today. This is what I tell myself. But really, I was a lonely child who couldn’t stand the silence.

Louise Bourgeois wrote: “You pile up associations the way you pile up brick. Memory itself is a form of architecture.”[3]

These pages are my building. I built it for us. Come in. Tell me a story. I love you. Stay.

Notes

1. Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts, Graywolf Press, 2015, p. 113.

2. Maggie Nelson, Bluets, Wave Books, 2009, p. 28.

3. Joseph Helfenstein, “Louise Bourgeois: Architecture as a Study in Memory,” in Jerry Gorovoy and Danielle Tilkin, eds, Louise Bourgeois: Memory and Architecture, Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia, 1999, p. 26.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

One of the many wonderful things about stories is they can touch the life of an old friend many years later and more than an ocean away. We are bound by this- our shared love of life, of family, of friends, of the brief moments we have together.