For architect and artist Sarri Elfaitouri, starting from scratch in Benghazi is an existential necessity. After the March 2023 demolition of the city’s historical center, he reflects on urbanism, social reforms, and the legacy of colonialism in Libya.

A tabula rasa — a clean slate. This was the intention behind the demolition of Benghazi’s historical center back in March 2023, which included several buildings of Italian colonial heritage.

Erasure is nothing new to Benghazi. Deeply affected by WW2 bombing by both the Allies and the Axis, the city was later rebuilt by the kingdom, which got rid of the post-war remnants in order to redevelop a new modern center. But this too was again destroyed by the 2014-2018 civil war.

A rebuilding operation is effectively ongoing, but from a conservation standpoint, the demolition has destroyed a big part of the modern history of Libya. While some mourn the loss, others try to look at the erasure process as a chance to build a new narrative for the country, to move lightly forward unburdened by the past.

“Architecture in Libya is deeply entangled with the country’s problematic past, rooted in fundamentalist, nationalist, and colonial ideologies,” says Sarri Elfaitouri, founder of the Tajarrod Architecture and Art Foundation in Benghazi. “There is a necessity for reconstruction as a socio-cultural reform.”

Moved by the post-war destruction of the Benghazi center, the young Libyan architect, artist, writer, and curator realized that throughout the course of Libyan history, the material reconstruction of buildings has in fact never produced any radical change in how the culture understands its past.

Elfaitouri conceives architecture in its higher incarnation, namely as a cultural project based on theory, research, and experimentation. With Tajarrod, the aim is to move away from commercialism, and away from the traditional office practice – what he calls “the cornering of the market.” The idea is to provide the right atmosphere for young architects, artists, and students to re-think Libya and its buildings.

The architect therefore de-facto questions the possibilities and potentials of today’s Benghazi, and its ability to absorb tragedies, tension, reinvention, and change.

Naima Morelli: You studied architecture at Girne American University in Cyprus and came back to Benghazi in 2018. Can you tell me how the city changed over that period of time, and how you felt witnessing the destruction?

Sarri Elfaitouri: When I went back in 2018, the country had just emerged from the civil war that started in 2014 against religious fundamentalist terrorism. Benghazi’s old center was significantly damaged, having been one of the most intense fronts in the conflict. The city had almost entirely lost its historical architectural characteristics in the ashes, and for some, its “identity” as well.

I was first struck by mixed feelings when I saw the unimaginable destruction, and then witnessed how the area’s displaced citizens slowly returned to their destroyed and semi-destroyed homes to revitalize them with life – with zero governmental support! Important buildings and spaces gradually resumed some functionality thanks to the efforts of ordinary citizens, and I felt the presence of a minor social will for revival, after the area had been very generally abandoned.

I was not particularly sad, even though the condition was disastrous! It was a moment that provoked a deep suspicion in me towards identity, architecture, and architects who were obviously helpless in the face of such destruction, as they are traditionally and commercially trained to be. At the same time it felt like a moment of liberation, where starting from scratch is an existential necessity.

Government initiatives began only two years ago to restore and renovate some buildings such as the Parliament Dome, Omar Al Mukhtar Tomb, and to transform the Cathedral into a mosque. All initiatives were undertaken in a random and superficial way, without any critical understanding of the city’s problematic colonial history or with any vision for a transformative reconstruction.

NM: In your opinion, what are the most significant examples of Italian colonial architecture in Benghazi which are still standing?

SE: I would say Al Manar Palace, because of its ambivalent status as both an interesting and problematic architectural piece. In its design it incorporates elements from this country’s Islamic architecture, such as the minaret and the arches; however, it does so in a way that blends with the modern Italian architectural style.

This is interesting for me as it represents how Italian architecture in Libya is inseparable from colonial ideology and politics. In fact, the Italian colonial government successfully achieved an architectural hegemony that many Libyans accepted as part of Libyan identity. But this was actually an orientalist architectural injection in Libyan culture.

That bing said, I would not necessarily classify this example as significant in either a positive or negative way. It is rather significant for the cultural and ideological aspects that transcend its material and historical existence, which is both unique and alarming.

NM: How was Al Manar Palace perceived by Libyans over time?

SE: Al Manar Palace has taken on various social and symbolic functions throughout its history, most notably, its transition from a palace for the Italian governors, to the dwelling of King Idres, who famously declared Libyan independence from the palace in 1951.

However, on a broader cultural level, I can only speculate that there has been a division between people who perceive this architecture as part of Libyan identity and others — the majority I believe — who are either indifferent to it, or reject its relevance to Libyan society. There is a rupture between an identification with the colonial architectural heritage, which I call “colonial contextuality,” and a denial of it.

Several Libyan researchers value Italian colonial architecture and urbanism for the initial social and infrastructural benefits they provided to the city, and for the “respect” the Italian architects demonstrated in incorporating local architectural “styles” — namely oriental and Mediterranean, into their designs. They call it “revival,” while I call it an unacknowledged submission to imperialist ideology at worst, and cultural blindness at best.

As Edward Said said, imperialism still exists.

NM: Can you tell me how some of Tajarrod’s projects tackled the meaning of the colonial heritage of Benghazi, including Al Manar Palace?

SE: Colonial heritage is a stubborn question that emerges in every project we work on in Tajarrod, and we approach it through three main axes: pedagogical, socio-spatial, and archival.

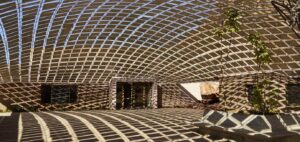

In our first project Tahafut/Incoherence in 2020, we organized a pedagogical workshop that led to a three-day urban installation and exhibition in front of the Al Manar Palace, in Al Khalsa/Silphium Square, the former Piazza XXVIII Ottobre.

The project aimed to critically repair that colonial context, to present it as a space of collective healing from a traumatic past and against its forgetting, denial, and erasure. The event mainly centered on attracting architects, artists and local residents and gathering them together in order to actively discuss the issues of destruction, reconstruction, and identity in a public space.

It was not an architectural initiative in the traditional sense, but more of a tactical urban one, based on installing low-budget light structures to shape the space physically and conceptually and then generating movement and discourse inside it.

NM: With Tajarrod, you have been involved in a cross-regional project called “the Placeless Academy,” which confronts issues related to the complex heritage of colonial and fascist architecture. Can you tell me how you worked on the topic of re-evaluating the legacy of modern architecture in Benghazi?

SE: We highlighted Omar Almukhtar Street as a case study. In response to the destruction and reconstruction project I mentioned previously, we questioned what it means to reconstruct a symbolic street, first built by Italian colonial powers and then re-appropriated and named after the leader of the resistance movement.

Even if an actual reconstruction project isn’t possible, the participants in the project designed speculative works that critiqued both the colonial legacy and the present governmental reconstruction project.

One of the interesting ideas produced was the potential for redesigning a prototypical street that could represent a regional and international symbol for resistance, as there are already several streets in the world that hold the same name, that of leader of the Libyan resistance movement.

Such efforts are dedicated to reshaping the Libyan narrative that was partly constructed by Western colonial and present political powers, and therefore, to establishing a counter-archive that is ongoing, ever-renewing, and resistant to hegemony, nostalgia, and denial.

NM: Is the Libyan population interested in preserving their architectural heritage in the face of development and political change?

SE: As I mentioned earlier, there is currently some emphasis on preservation, though it seems so to me merely an ambitious idea on behalf of an elite intellectual and cultural minority, many of whom had already been historically privileged and benefited from or against the Italian colonial presence in the city – merchants, politicians, and activists.

I don’t believe that what’s going on now is a sincere development project, it is only using architecture and reconstruction as political antidotes to numb the rage and dissatisfaction of the people. Nor do I think that there is serious political change when what we experience is only a reproduction/reorganization of the same authoritarian, oppressive, demagogic, and exploitive structures, discourse, and dynamics that the previous regime (Gaddafi’s) had long practiced. The difference is that now it’s simply perpetuated while being camouflaged by a military emancipatory narrative.

Drawing from “the Comprehensive Survey of the Views of Libyans on Values,” published in 2015 by the University of Benghazi’s Center for Research and Consultancy, and from the current concrete realities, the Libyan population in general seems mainly concerned with surviving and thriving individually, after the last collective ambition (the Feb. 17th revolution in 2011) “failed” them. Architectural heritage preservation seems too much not only like a luxury that Libyans can’t afford, but a regressive one that is also meaningless to them.

One could deduce that there is an intense contradiction in Libyan culture presently. On the one hand, there is a ferocious desire for a radical erasure and break with the built/material traces of the past, reflected in the negligence and abandonment of traditional aesthetics, costumes, and architecture. And on the other, a pull toward only reproducing the old social and political value systems, with all their malfunctions and corruptions.